The Banke Chamar: Forgotten Revolutionary of 1857

क्या खूब लड़ा वो जौनपुर का जाबाज़ , पकड़ न पायी जिसको अंग्रेज़ो की सरकार , नाम था उसका बांके चमार

The annals of India’s first war of independence in 1857 are filled with stories of courage, sacrifice, and resistance against British colonial rule. While mainstream historical narratives have long celebrated figures like Mangal Pandey, Rani Lakshmi Bai, and Nana Saheb, the contributions of countless other freedom fighters, particularly those from marginalized communities, have remained in the shadows. Among these forgotten heroes stands Banke Chamar (1820-1857), a revolutionary whose extraordinary courage and leadership in the Jaunpur region of Uttar Pradesh posed such a significant threat to British authority that they placed an unprecedented bounty of ₹50,000 on his head—equivalent to several crores in today’s currency. wikipedia+1

Historical Context and the Chamar Community

Social Structure in 19th Century India

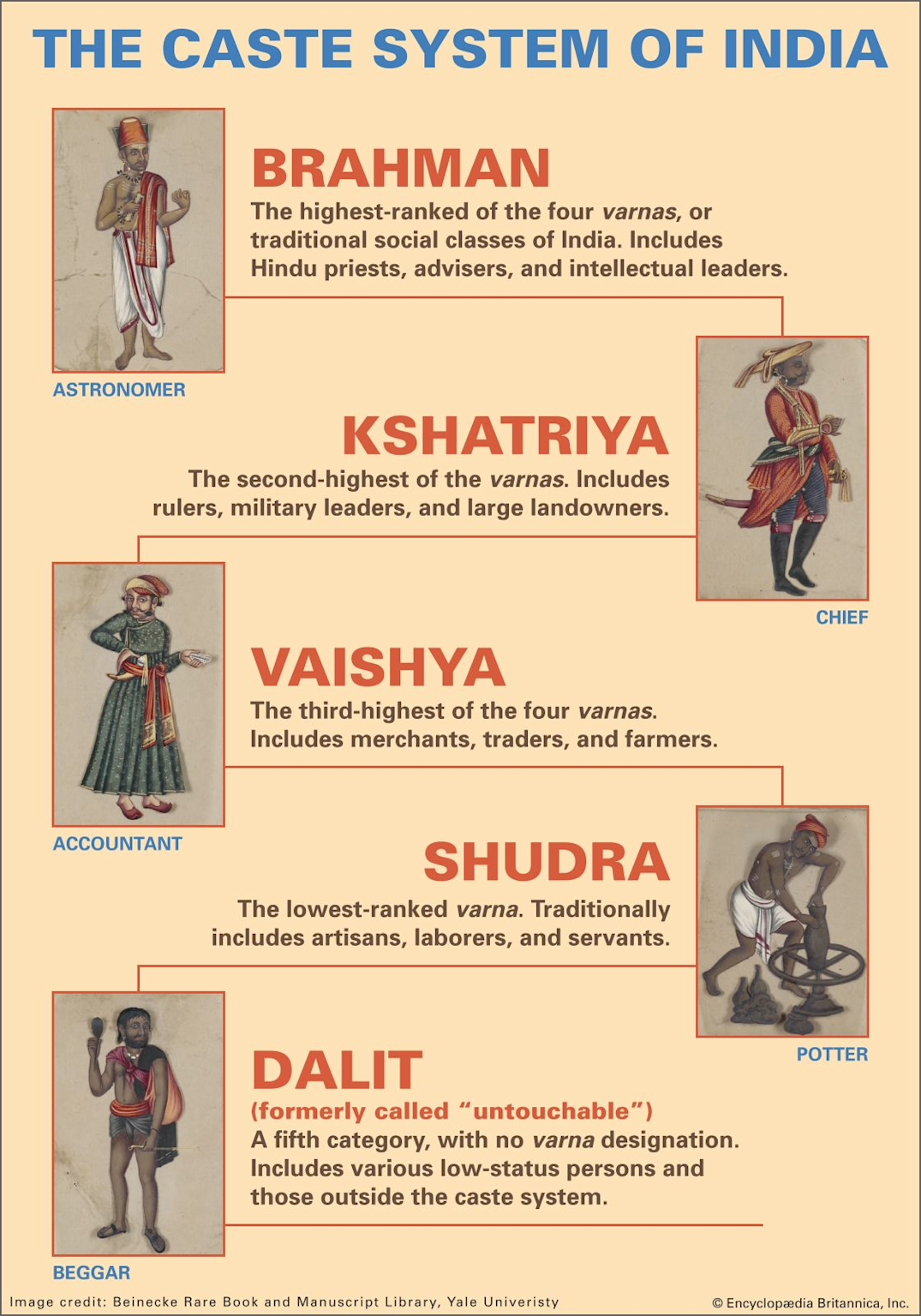

The story of Banke Chamar cannot be understood without examining the complex social fabric of 19th century India, particularly the position of the Chamar community within the rigid caste hierarchy. The Chamars, traditionally associated with leather work, constituted one of the largest Scheduled Caste communities in northern India, primarily concentrated in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Punjab. Despite their significant numbers—with Chamars comprising over 11% of Uttar Pradesh’s population according to modern census data—they occupied one of the lowest positions in the traditional Hindu caste system. joshuaproject+1

The caste system of India illustrating the hierarchy of varnas and the Dalit category outside the traditional varnas triumphias

The British colonial administration, while ostensibly maintaining neutrality in caste matters, often exploited these social divisions for administrative convenience. Colonial ethnographic surveys and settlement reports consistently categorized Chamars primarily as leather workers, though evidence suggests many were actually involved in agriculture as peasants, sharecroppers, and laborers. This occupational stereotyping served to reinforce existing social hierarchies while facilitating British revenue administration. foundation-chamar.squarespace

The Chamar Community’s Agrarian Roots

Recent scholarship has revealed that contrary to colonial stereotypes, many Chamars in the 19th century were significantly involved in agriculture. Settlement reports from the 1870s and 1880s document Chamar families holding occupancy rights, participating as sharecroppers, and even acquiring small proprietary holdings in various districts of Uttar Pradesh. In Jaunpur district specifically, where Banke Chamar lived, many Chamar families had established themselves as cultivators and maintained complex relationships with the land revenue system. foundation-chamar.squarespace

Early Life and Background of Banke Chamar

Banke Chamar was born on July 27, 1820, in Kuarpur village, located in the Machhali Shahar tehsil of Jaunpur district, Uttar Pradesh. Born into a Chamar family during a period of increasing British consolidation in northern India, Banke grew up witnessing the gradual erosion of traditional power structures and the imposition of alien administrative systems. His birthplace, Kuarpur, was situated in a region that had long been a crossroads of political and cultural influences, having served under various rulers including the Nawabs of Awadh and later coming under direct British administration. wikipedia+1

The Jaunpur district in the early 19th century was characterized by complex land tenure arrangements, with a mixture of traditional zamindari holdings and newer revenue settlements imposed by the British. This region had experienced significant administrative changes, having been transferred from the dominion of Benares in 1788 and finally established as a separate district in 1818, just two years before Banke’s birth. These administrative upheavals created an atmosphere of uncertainty and resentment that would later fuel revolutionary activities. ijcrt+1

The 1857 Rebellion in Jaunpur

Prelude to Revolution

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 did not emerge in isolation but was the culmination of decades of growing resentment against British policies. In Jaunpur, as elsewhere, multiple factors contributed to the explosive situation: the Doctrine of Lapse had dispossessed traditional rulers, land revenue policies had impoverished cultivators, and social reforms had threatened traditional customs. The immediate trigger—the controversy over greased cartridges—provided a unifying cause around which diverse grievances could coalesce. wikipedia+1

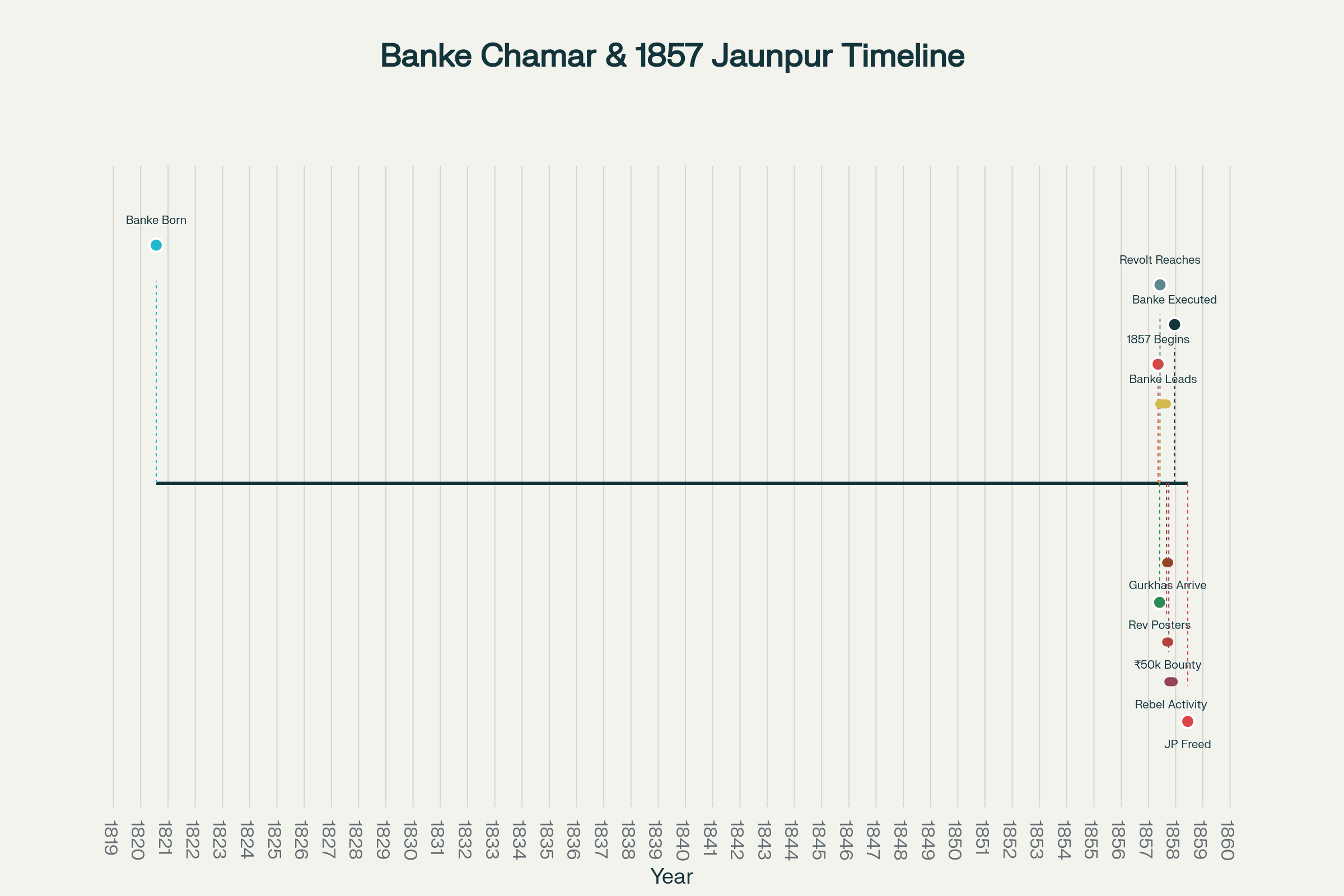

Timeline of Banke Chamar’s Life and the 1857 Rebellion in Jaunpur

By May 31, 1857, revolutionary posters had appeared throughout Jaunpur, and instructions had been issued to native soldiers to deposit their arms. The atmosphere was charged with anticipation and defiance. On June 5, 1857, news of the rebellion reached Jaunpur from Benares, specifically reports that British troops had opened fire on a Sikh regiment. This news electrified the local Sikh garrison, who immediately rose in revolt. ijcrt+1

The Jaunpur Uprising

The rebellion in Jaunpur began with the Sikh troops stationed there, who, enraged by news from Benares, shot dead the Joint Magistrate Mr. Cuppage and opened fire on their commanding officers. The treasury guard under Lieutenant Mara was overwhelmed, and within hours, effective British control over the district had collapsed. The magistrate, Mr. H. Fane, fled along with other British officials, leaving the field open for rebel leaders to emerge. ijcrt+1

It was in this chaotic but opportune moment that Banke Chamar stepped forward as a leader. Working under the broader leadership of Harpal Singh, who was coordinating revolutionary activities in the region, Banke demonstrated exceptional organizational skills and military acumen. His leadership was particularly significant because it bridged social divides—a Chamar effectively leading a multi-caste rebellion in a society where such leadership would have been unthinkable under normal circumstances. youtuberavidassia.wordpress

Banke Chamar’s Revolutionary Activities

Military Leadership and Guerrilla Warfare

Banke Chamar’s approach to fighting the British was characterized by guerrilla tactics and intimate knowledge of local terrain. Along with his core group of 17-18 associates, he conducted systematic attacks on British positions, supply lines, and isolated outposts. These operations were not merely destructive but strategically planned to disrupt British administration and encourage wider participation in the rebellion. wikipedia+2

The effectiveness of Banke’s operations can be gauged from the British response. Colonial records indicate that his activities caused significant disruption to revenue collection, postal services, and general administration in the region. His group’s ability to appear suddenly, strike effectively, and disappear into the countryside before British reinforcements could arrive made them particularly dangerous to colonial authority. iisjoa

Social Significance of His Leadership

What made Banke Chamar’s leadership particularly remarkable was its social implications. In a society where caste hierarchies traditionally determined leadership roles, a Chamar commanding respect and allegiance from diverse social groups represented a fundamental challenge to established norms. His success in rallying people from different castes and communities demonstrated that the struggle against colonial rule had the potential to transcend traditional social barriers. iisjoa

This cross-caste solidarity was not merely tactical but reflected deeper currents of resistance that the 1857 rebellion had unleashed. The shared experience of colonial oppression had created new bases for unity that cut across traditional divisions. Banke’s leadership embodied this transformative potential of anti-colonial struggle.

Historical illustration of the 1857 Indian rebellion depicting sepoys fighting British forces with traditional weapons and attire commons.wikimedia

The British Response and the ₹50,000 Bounty

An Unprecedented Reward

The British administration’s decision to place a bounty of ₹50,000 on Banke Chamar’s head was unprecedented for someone from his social background. To understand the magnitude of this sum, it’s crucial to consider the purchasing power of money in 1857. Contemporary accounts suggest that basic necessities were extremely cheap—two cows could be purchased for six paisa, and a month’s ration for a family could be bought for a few annas. In today’s terms, the ₹50,000 bounty would be worth several crores of rupees, making it one of the largest rewards announced during the entire 1857 rebellion. wikipedia+2youtube+1

This enormous bounty reflected both the effectiveness of Banke’s operations and the serious threat he posed to British authority. The fact that such a reward was placed on a Chamar—a community that colonial administrators typically dismissed as politically insignificant—indicates the extent to which the rebellion had disrupted established social and political categories.

Military Operations Against the Rebels

The British response to the Jaunpur rebellion was systematic and brutal. Colonel Wroughton arrived with Gurkha forces from Azamgarh on September 8, 1857, beginning a campaign to restore British control. The rebels, including Banke Chamar and his associates, initially managed to evade capture through superior knowledge of local terrain and strong community support. ijcrt+1

However, the disparity in resources and firepower eventually told. The British could call upon reinforcements from other regions, had superior weaponry, and could sustain longer campaigns. The rebels, despite their courage and local support, lacked the resources for prolonged resistance against a determined colonial state.

Capture and Martyrdom

Betrayal and Arrest

Like many revolutionary movements, the 1857 rebellion in Jaunpur ultimately suffered from internal betrayals. Despite the large bounty, Banke Chamar and his associates had initially evaded capture through community support and their own operational security. However, as British pressure intensified and the rebellion began to falter elsewhere, local dynamics changed. youtube+1

The eventual capture of Banke Chamar came through betrayal by informers (Ramashankar Tiwari) who were motivated by the enormous reward offered by the British. This betrayal was particularly bitter because it came from within the local community, highlighting the divisive effects of colonial policies that pitted Indians against each other through economic incentives. altnewsyoutube

Execution and Its Significance

On December 18, 1857, Banke Chamar was executed by hanging, along with his 18 associates. This mass execution was intended to serve as a deterrent to others who might be contemplating resistance against British rule. The British authorities chose hanging—a method that was both public and humiliating—to maximize the psychological impact of these executions. wikipedia+1

The execution of Banke Chamar and his companions marked the end of organized resistance in the Jaunpur region. By June 12, 1858, the district was declared completely free from rebel activities. However, the memory of their sacrifice continued to inspire future generations of freedom fighters and became an integral part of local folklore and resistance traditions. ijcrt

Illustration of sepoy soldiers during the 1857 Indian Rebellion, showcasing their diverse military attire and formation under colonial architecture britannica

Historical Context of Dalit Participation in 1857

Broader Pattern of Dalit Involvement

Banke Chamar was not an isolated example of Dalit participation in the 1857 rebellion. Across northern and central India, members of various Dalit communities played significant roles as leaders, soldiers, and supporters of the anti-colonial struggle. Matadin Bhangi, a Valmiki worker in a cartridge manufacturing unit, is credited with alerting Mangal Pandey to the religious implications of the greased cartridges, thus playing a crucial role in triggering the rebellion. Chetram Jatav and Ballu Mehtar from Etah district, Uda Devi Pasi from Lucknow, and many others demonstrated that the desire for freedom transcended caste boundaries. iisjoa+1

This widespread Dalit participation challenges colonial-era narratives that portrayed the rebellion as primarily an upper-caste Brahmin and Kshatriya affair. Modern scholarship has revealed that Dalit communities had their own reasons for opposing British rule, including opposition to discriminatory policies, land revenue demands, and forced labor practices. forwardpress+1

Motivations for Dalit Resistance

The reasons for Dalit participation in the 1857 rebellion were complex and multifaceted. While they faced oppression within traditional Indian society, many Dalits found that British rule had not improved their condition and had, in some ways, made it worse. Colonial land revenue policies had disrupted traditional patron-client relationships without providing alternative sources of livelihood security. The British administrative system, while ostensibly merit-based, in practice often reinforced existing social hierarchies. questjournals

Moreover, for many Dalit communities, the rebellion represented an opportunity to assert their dignity and agency in ways that traditional society had denied them. The shared experience of fighting against colonial oppression created new forms of solidarity that transcended caste boundaries, as evidenced by Banke Chamar’s successful leadership of a multi-caste rebel group.

The Chamar Community in Historical Perspective

Beyond Occupational Stereotypes

The story of Banke Chamar illuminates the limitations of colonial-era categorizations that reduced complex communities to simple occupational labels. While Chamars were traditionally associated with leather work, historical evidence suggests that their actual economic activities were much more diverse. Many Chamars were involved in agriculture, trade, and other occupations, and some had achieved considerable economic success, particularly in areas connected to the British leather trade. wikipedia+1

The rigid occupational categorization imposed by colonial administrators served administrative convenience but failed to capture the dynamic reality of caste communities. Banke Chamar’s emergence as a military leader demonstrates the capabilities that existed within Dalit communities but were often suppressed or ignored by both traditional Indian society and colonial administrators.

Social Mobility and Identity Formation

The 19th century was a period of significant social transformation for many Dalit communities, including the Chamars. The disruption of traditional social structures by colonial rule created both opportunities and challenges. Some Chamar families achieved economic prosperity through involvement in British commercial enterprises, while others faced new forms of exploitation through colonial land and labor policies. wikiwand

This period also witnessed early attempts at social reform and identity reconstruction within Chamar communities. Leaders began to articulate alternative histories that challenged caste-based stigmatization, claiming Kshatriya heritage and developing new religious and cultural practices. While these movements gained momentum in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the seeds of such transformations were already visible during the 1857 rebellion period. wikiwand

Legacy and Historical Memory

Marginalization in Mainstream Narratives

Despite their significant contributions, Dalit freedom fighters like Banke Chamar were largely marginalized in colonial and post-colonial historical narratives. British colonial historians, focused on understanding the rebellion in terms of their own categories of significance, tended to emphasize the roles of traditional rulers and upper-caste leaders while downplaying the participation of marginalized communities. iisjoa

This marginalization continued in early post-independence historiography, which often adopted similar frameworks and sources. The result was a historical narrative that severely underrepresented the contributions of Dalit communities to India’s freedom struggle, creating a distorted picture of both the 1857 rebellion and the broader anti-colonial movement.

Contemporary Relevance and Recognition

In recent decades, there has been growing recognition of the need to recover and document the contributions of marginalized communities to India’s freedom struggle. Dalit political movements, academic scholars, and cultural organizations have worked to bring figures like Banke Chamar out of historical obscurity and into mainstream consciousness. roundtableindia

This process of historical recovery is not merely about correcting past omissions but has contemporary political and social significance. It challenges narratives that portray Dalits as passive recipients of upper-caste or government benefits and highlights their agency and leadership capabilities. The story of Banke Chamar serves as a powerful counter-narrative to caste-based discrimination and stereotyping.

Historiographical Challenges and Sources

Problems of Documentation

Reconstructing the life and activities of figures like Banke Chamar faces significant challenges due to the nature of available sources. British colonial records, while extensive, were produced by administrators who were often unfamiliar with local societies and were primarily concerned with maintaining order and extracting revenue. Their accounts frequently reflect cultural biases and limited understanding of the communities they were documenting. iisjoa

Local oral traditions have preserved many stories about Dalit freedom fighters, but these sources require careful analysis to separate historical facts from later embellishments. The challenge for historians is to develop methodologies that can effectively utilize both colonial archives and oral traditions while accounting for their respective limitations and biases.

Recent Scholarly Approaches

Modern scholarship on the 1857 rebellion has increasingly adopted subaltern perspectives that foreground the experiences of marginalized communities. This approach has revealed the complexity of Dalit participation in anti-colonial struggles and challenged simplistic narratives about caste and resistance. pratilipi

Scholars like Ramnarayan Rawat have demonstrated how careful analysis of colonial land revenue records can reveal the substantial involvement of Chamar communities in agriculture, thus challenging occupational stereotypes and providing evidence for more complex understanding of their social and economic positions. Such research provides the foundation for more accurate historical narratives about figures like Banke Chamar. foundation-chamar.squarespace

Conclusion

The story of Banke Chamar represents far more than the biography of a single individual—it illuminates fundamental aspects of Indian society, colonial rule, and anti-colonial resistance that have long been obscured by mainstream historical narratives. His emergence as a leader during the 1857 rebellion demonstrates the transformative potential of anti-colonial struggle to challenge and transcend traditional social hierarchies. iisjoa

The enormous bounty placed on his head by the British—₹50,000, equivalent to crores in today’s currency—testifies to the serious threat he posed to colonial authority and the effectiveness of his resistance activities. His ability to lead a multi-caste rebel group in a highly stratified society speaks to both his personal capabilities and the unifying power of shared opposition to colonial oppression. wikipedia+1

Most significantly, Banke Chamar’s story challenges us to reconsider our understanding of India’s freedom struggle. It reveals that resistance to colonial rule was not confined to traditional elites but emerged from all sections of society, including those who faced discrimination within Indian society itself. His sacrifice, along with that of his 18 associates, contributed to a tradition of resistance that would ultimately culminate in Indian independence. wikipedia

The marginalization of figures like Banke Chamar in historical narratives reflects broader patterns of social exclusion that have persisted from colonial times into the present. Recovering and celebrating these stories is therefore not merely an exercise in historical correction but a necessary step toward creating more inclusive and accurate accounts of India’s past. In honoring the memory of Banke Chamar, we acknowledge the contributions of countless other forgotten heroes whose sacrifices helped shape the trajectory toward freedom and justice.

Today, as India continues to grapple with issues of caste discrimination and social inequality, the story of Banke Chamar serves as a powerful reminder that courage, leadership, and patriotism are not confined to any particular social group. His life and sacrifice stand as testament to the universal human aspiration for dignity, freedom, and justice—values that transcend the artificial boundaries of caste, class, and social status.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banke_Chamar

- https://www.altnews.in/photo-of-kaibarta-eastern-bengal-shared-as-dalit-freedom-fighter-banke-chamar-and-udaiya-chamar/

- https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/16561/IN

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chamar

- https://foundation-chamar.squarespace.com/s/Rawat-Writing-Dalit-History.pdf

- https://hi.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E0%A4%AC%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%82%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%87_%E0%A4%9A%E0%A4%AE%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B0

- https://ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2401645.pdf

- https://jaunpur.nic.in/history/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Rebellion_of_1857

- https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/revolt-of-1857/

- http://www.brandbharat.com/english/up/districts/Jaunpur/history_Jaunpur.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6w_OLrCJJCU

- https://ravidassia.wordpress.com/2010/02/14/chamars/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Banke_Chamar

- http://iisjoa.org/sites/default/files/iisjoa/July%202024/16th%20Paper.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-nl91xw9IQ

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matadin_Bhangi

- https://www.forwardpress.in/2024/03/dalit-reading-of-1857-mutiny/

- https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol12-issue1/1201199202.pdf

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/chamar

- https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/dalits-in-freedom-movement-a-year-of-academic-events/

- https://www.pratilipi.in/2008/06/the-role-of-dalits-in-the-1857-revolt-badri-narayan/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PggPWP83RYQ

- https://www.instagram.com/p/C6-nkj7S1cc/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cg6UvLk3ZqI

- https://www.worldhindunews.com/dalit-contributions-to-the-first-war-of-independence-in-1857/

- https://www.instagram.com/reel/C4qp6losTVD/?hl=en

- https://sahityanama.com/Banke-Chamar

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uda_Devi

- https://ravidassia.wordpress.com/chamars-in-the-military/

- https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/unsung-heroes-detail.htm?11011

- https://www.rediff.com/news/report/revolt/20051110.htm

- https://newschecker.in/hi/fact-check-hi/freedom-fighter-banke-chamar-viral

- https://en.themooknayak.com/bahujan-nayak/the-forgotten-bahujan-warriors-of-indias-first-war-of-independence-rescuing-the-braveheart-stories-of-the-indian-mutiny

- https://www.newslaundry.com/2024/08/15/the-dalit-revolutionaries-from-chambals-ravine

- https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/revolt-of-1857/

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Indian-Rebellion-of-1857

- http://indianculture.gov.in/digital-district-repository/district-repository/sikh-sepoys-revolt-against-british-jaunpur

- https://www.csirs.org.in/uploads/paper_pdf/evolution-of-chamar-and-jatav-mahasabha-for-dalit-society-in-united-provinces.pdf

- https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/why-did-indian-mutiny-happen

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaunpur,_Uttar_Pradesh

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22165162/

- https://www.drishtiias.com/to-the-points/paper1/revolt-of-1857

- https://jaunpur.dcourts.gov.in/about-department/history/

- https://oaji.net/pdf.html?n=2021%2F1201-1615364642.pdf

- http://mu.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/FYBA-History-Paper-I-History-of-Modern-India-Revised-Syllabus-2018-19.pdf