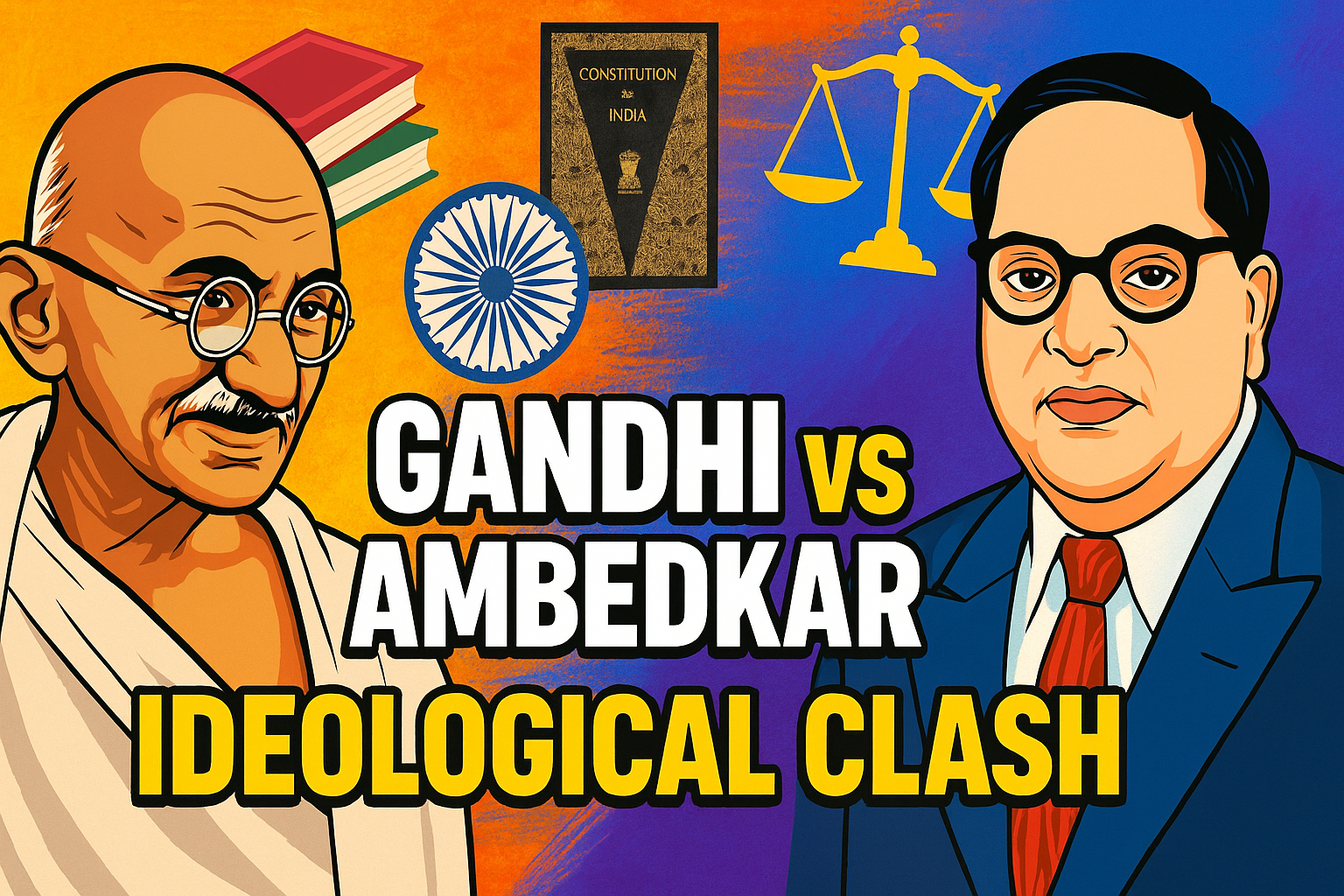

Ambedkar vs Gandhi: Clash of Civilizational Visions and Their Ideological Divergence on Caste and Reform

The ideological conflict between Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi represents one of the most profound philosophical debates in modern Indian history, embodying fundamentally different visions for India’s civilizational future. While both leaders shared a commitment to social justice and the upliftment of marginalized communities, their approaches to caste reform, religious identity, and democratic governance diverged so dramatically that they came to represent competing paradigms for India’s transformation. Ambedkar advocated for the complete annihilation of the caste system through constitutional mechanisms and legal frameworks, while Gandhi sought to reform Hinduism from within through moral persuasion and spiritual transformation. This clash was not merely about tactics but represented a deeper disagreement about whether India’s traditional social structures could be purified and reformed, or whether they required complete dismantling and replacement with modern, egalitarian institutions. [1][2][3][4][5]

Historical Context and Personal Backgrounds

The Gandhi-Ambedkar debate emerged from vastly different lived experiences that shaped their worldviews. Mahatma Gandhi, born into a privileged Gujarati family in 1869, experienced caste discrimination only peripherally when he was excommunicated from his community for traveling to England. His approach to social reform was thus informed by his position as an upper-caste reformer seeking to purify Hindu society from within. Gandhi’s encounters with discrimination came primarily through his experiences in South Africa, where he developed his philosophy of satyagraha as a means of combating racial prejudice. [1][4][6]

In stark contrast, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was born in 1891 into a Mahar family, considered “untouchable” under the Hindu caste system. His personal experiences of humiliation and systematic exclusion from childhood through his educational journey provided him with intimate knowledge of caste oppression’s psychological and social dimensions. Despite achieving extraordinary academic success at prestigious institutions like Columbia University and the London School of Economics, Ambedkar never escaped the stigma of his caste origins, which fundamentally shaped his radical critique of Hindu social organization. [4][7][8][1]

This divergence in personal experience translated into fundamentally different understandings of the nature and urgency of caste reform. Gandhi approached untouchability as an unfortunate distortion of what he believed was originally a harmonious varna system, while Ambedkar viewed the caste system as an inherently oppressive structure that could not be reformed but only annihilated. [2][3]

Gandhi’s Vision: Reform Within Tradition

Gandhi’s approach to caste reform was rooted in his belief that Hinduism, properly understood, was inherently just and that the caste system represented a corruption of the original varna framework. He distinguished between varna, which he saw as a natural division of labor based on individual aptitude and social function, and caste, which he acknowledged had degenerated into a rigid hierarchy based on birth. In his interpretation, the varna system could serve as a framework for social harmony if properly implemented, with each group performing its designated role with equal dignity and mutual respect. [9][10][11][12]

Central to Gandhi’s civilizational vision was his belief in the possibility of moral transformation through personal purification and spiritual discipline. He launched extensive campaigns for temple entry, inter-dining, and the social inclusion of “Harijans” (his term for untouchables, meaning “children of God”), believing that appealing to the higher instincts of caste Hindus could bring about meaningful reform. His Harijan campaign of 1933-34, which covered 12,500 miles across India, demonstrated his commitment to changing hearts and minds through direct moral appeal. [13][14]

Gandhi’s response to Ambedkar’s “Annihilation of Caste” revealed the depth of his commitment to reforming Hinduism from within. In his critique, Gandhi argued that Ambedkar had “overproved his case” by focusing on the worst examples of Hindu practice rather than the religion’s highest ideals. He contended that “a religion has to be judged not by its worst specimens, but by the best it might have produced,” citing luminaries like Chaitanya, Ramakrishna Paramahansa, and Vivekananda as evidence of Hinduism’s essential nobility. This perspective reflected Gandhi’s fundamental belief that religious and cultural traditions could be purified and reformed rather than abandoned. [15]

Gandhi’s economic philosophy complemented his social reform agenda through his emphasis on village self-reliance and cottage industries. He envisioned a decentralized India composed of self-sufficient village republics where traditional occupational divisions would be maintained but stripped of hierarchical implications. This model sought to preserve India’s civilizational continuity while eliminating the oppressive aspects of caste practice. [9][5]

Ambedkar’s Vision: Radical Reconstruction

Ambedkar’s civilizational vision represented a fundamental rejection of Gandhi’s reformist approach. Having experienced the violence and humiliation of untouchability firsthand, Ambedkar argued that the caste system was not a corruption of Hinduism but its essential feature, sanctioned by religious texts and enforced through centuries of practice. In his seminal work “Annihilation of Caste,” Ambedkar declared that “the outcaste is a by-product of the caste system. There will be outcastes as long as there are castes. Nothing can emancipate the outcaste except the destruction of the caste system”. [16][3]

Ambedkar’s critique went beyond social practice to challenge the religious and philosophical foundations of Hindu society. He argued that Hindu scriptures themselves sanctioned caste hierarchy and untouchability, making reform from within impossible. His famous declaration that “religion is for man and not man for religion” reflected his pragmatic approach to spiritual matters, leading him ultimately to reject Hinduism entirely in favor of Buddhism. [17][18][19][16]

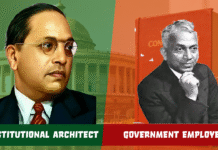

The constitutional framework that Ambedkar championed represented his vision of a modern, rational society based on individual rights rather than group identity. As chairman of the Constitution’s Drafting Committee, he embedded principles of equality, liberty, and fraternity that directly challenged traditional social hierarchies. His advocacy for reservations, separate electorates, and constitutional safeguards reflected his belief that legal and institutional mechanisms were necessary to protect marginalized communities from majoritarian oppression. [20][21][22][23]

Ambedkar’s economic thinking also diverged sharply from Gandhi’s village-centered model. He supported industrialization and state-led development as means to break caste-based occupational hierarchies and create opportunities for Dalit mobility. His vision of modernity embraced Western educational systems, scientific rationality, and bureaucratic governance as alternatives to traditional authority structures. [24][5]

The Poona Pact: Crystallizing the Conflict

The signing of the Poona Pact on September 24, 1932, represents the most dramatic confrontation between Gandhi’s and Ambedkar’s civilizational visions. The controversy emerged from the British government’s Communal Award, which granted separate electorates to various communities, including the “Depressed Classes” represented by Ambedkar. While Ambedkar viewed separate electorates as essential for ensuring authentic Dalit political representation, Gandhi saw them as a threat to Hindu unity and India’s national integration. [20][21][25][26]

Gandhi’s fast unto death in Yerwada Jail created enormous moral pressure that ultimately forced Ambedkar to abandon his demand for separate electorates in exchange for increased reserved seats within joint electorates. The Poona Pact increased Dalit representation from 71 to 148 seats in provincial legislatures, but Ambedkar later described the agreement as achieved through “blackmail” and a betrayal of Dalit political autonomy. [20][25][27]

This episode revealed the fundamental tension between Gandhi’s vision of a unified Hindu society and Ambedkar’s insistence on Dalit political independence. Gandhi’s willingness to fast unto death demonstrated his belief that separate electorates would “perpetuate divisions” and weaken India’s capacity for self-governance. Ambedkar’s capitulation under duress highlighted the constraints faced by Dalit leadership in a political system dominated by upper-caste interests. [26]

Religious Transformation and Civilizational Choice

The religious dimension of the Gandhi-Ambedkar conflict ultimately represented competing visions of Indian civilization itself. Gandhi’s Hinduism was inclusive, reformist, and centered on moral purification, while Ambedkar’s Buddhism represented a complete rejection of Hindu social organization in favor of egalitarian spiritual principles. [17][7]

Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism on October 14, 1956, along with nearly 400,000 followers, constituted the largest religious conversion in modern Indian history. This mass conversion was not merely a personal spiritual choice but a political statement about the impossibility of achieving equality within Hindu society. Ambedkar’s twenty-two vows administered to new converts explicitly rejected Hindu deities, scriptures, and practices while embracing Buddhist principles of equality and rationality. [7][18][28][17]

Gandhi’s reaction to Ambedkar’s conversion threats revealed his deep anxiety about Hindu social cohesion. He argued that conversion would deprive Hinduism of the opportunity for internal reform and potentially fragment Indian society along religious lines. This perspective reflected Gandhi’s belief that India’s civilizational unity depended on maintaining Hindu social structures while purifying them of discriminatory practices. [15]

Democratic Visions and Political Philosophy

The Gandhi-Ambedkar debate extended beyond caste to encompass fundamentally different conceptions of democracy and governance. Gandhi’s vision emphasized decentralized democracy through village panchayats, moral leadership, and consensus-building through traditional mechanisms. He was skeptical of parliamentary democracy and Western political institutions, preferring indigenous forms of governance that he believed were more suited to Indian conditions. [1][23][6]

Ambedkar’s democratic philosophy, by contrast, embraced liberal constitutional democracy with strong individual rights protections and institutional safeguards for minorities. He viewed parliamentary democracy as essential for protecting Dalit interests against majoritarian oppression and saw constitutional law as the primary instrument for social transformation. His insistence on separation of powers, judicial independence, and written constitutional guarantees reflected his belief that formal institutional structures were necessary to prevent the tyranny of traditional social hierarchies. [22][23][24][29][30]

This difference in democratic philosophy reflected deeper disagreements about human nature and social change. Gandhi’s emphasis on moral transformation assumed that individuals could transcend selfish interests through spiritual discipline, while Ambedkar’s constitutionalism reflected his belief that institutional constraints were necessary to check the abuse of power. [5][31]

Educational Philosophy and Social Transformation

The two leaders’ approaches to education further illustrated their different civilizational visions. Gandhi’s concept of “Nai Talim” or basic education integrated learning with productive work and emphasized moral character development alongside practical skills. His educational philosophy sought to preserve India’s craft traditions while eliminating social hierarchies, creating educated citizens who remained connected to village life and traditional occupations. [9]

Ambedkar’s educational philosophy embraced Western higher education, scientific rationality, and professional training as instruments of Dalit empowerment. He famously urged his followers to “educate, agitate, and organize,” viewing education as the primary means for developing critical consciousness and challenging traditional authority. His own educational achievements at Columbia and the London School of Economics demonstrated his belief in the transformative power of modern learning. [5][32]

This educational divide reflected broader philosophical differences about tradition and modernity. Gandhi sought to synthesize Western education with Indian values, preserving cultural continuity while promoting social reform. Ambedkar viewed traditional Indian education as complicit in maintaining caste hierarchy and advocated wholesale adoption of Western educational models as instruments of liberation. [5]

Contemporary Relevance and Ongoing Debates

The Gandhi-Ambedkar debate continues to shape contemporary Indian politics and social policy, with their competing visions influencing discussions about reservations, caste census, and social justice. Gandhi’s emphasis on moral transformation and gradual reform resonates with those who advocate working within existing institutions, while Ambedkar’s structural critique provides intellectual foundations for movements demanding radical social change. [32][33][34]

Contemporary India’s reservation system, enshrined in the Constitution that Ambedkar helped draft, represents the institutionalization of his vision of affirmative action as necessary for achieving substantive equality. However, the persistence of caste-based discrimination and violence suggests that legal remedies alone are insufficient, validating aspects of Gandhi’s emphasis on changing social attitudes and practices. [33][34][35]

The rise of Dalit assertion movements, Buddhist conversion movements, and anti-caste activism in contemporary India reflects the ongoing relevance of Ambedkar’s radical critique. Simultaneously, Gandhian principles continue to influence rural development programs, environmental movements, and efforts at conflict resolution through moral persuasion. [5][8][32]

Economic Models and Development Strategies

The economic dimensions of the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate reflect broader questions about India’s development trajectory and relationship to modernity. Gandhi’s vision of village-centered, craft-based production represented an alternative to both capitalist industrialization and state socialism. His emphasis on khadi, cottage industries, and economic self-reliance sought to create prosperity without destroying traditional social fabric or environmental sustainability. [10][5]

Ambedkar’s economic thinking embraced industrialization and state-led development as necessary for breaking caste-based occupational hierarchies. He supported public sector enterprises, labor rights, and economic policies designed to create mobility opportunities for marginalized communities. His approach viewed traditional economic arrangements as inherently exploitative and sought to replace them with modern, merit-based systems. [5]

This economic divide reflected deeper philosophical differences about the relationship between tradition and progress. Gandhi’s economics sought to preserve India’s civilizational values while improving material conditions, while Ambedkar viewed traditional economic arrangements as inseparable from caste oppression and requiring complete transformation.

Constitutional Legacy and Institutional Framework

Ambedkar’s role as principal architect of India’s Constitution represents perhaps his most enduring contribution to resolving the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate through institutional mechanisms. The Constitution’s provisions for fundamental rights, directive principles, and affirmative action attempt to balance individual liberty with social justice, incorporating elements of both leaders’ visions. [23][30][32][33]

Article 17’s abolition of untouchability reflects both Gandhi’s moral critique and Ambedkar’s legal approach, while the reservation system institutionalizes Ambedkar’s demand for affirmative action. The Constitution’s embrace of parliamentary democracy with strong judicial review accommodates Ambedkar’s liberalism while its emphasis on village panchayats acknowledges Gandhi’s preference for decentralized governance. [33][35][23]

The constitutional framework thus represents a synthesis of their competing visions, though tensions between individual rights and community identity continue to generate political controversy. Contemporary debates about caste census, reservation expansion, and minority rights reflect ongoing efforts to balance the Gandhian emphasis on national unity with the Ambedkarite insistence on structural transformation. [36]

Conclusion: Synthesis and Continuing Tensions

The Gandhi-Ambedkar debate ultimately represents a fundamental tension between reform and revolution, tradition and modernity, moral transformation and structural change that continues to shape Indian society. While Gandhi’s vision of gradual reform through moral persuasion appealed to those committed to preserving cultural continuity, Ambedkar’s demand for systematic dismantling of oppressive structures provided a more radical path to equality. [5][31][32][34]

Contemporary India’s approach to social justice incorporates elements of both visions through constitutional guarantees, affirmative action policies, and ongoing efforts at social reform. However, the persistence of caste-based discrimination and inequality suggests that neither moral persuasion alone nor legal remedies alone are sufficient to achieve the egalitarian society both leaders envisioned. [33][34]

The enduring relevance of their debate lies not in choosing between their approaches but in recognizing the complementary nature of moral transformation and structural change in addressing deep-seated social inequalities. Gandhi’s emphasis on changing hearts and minds remains essential for creating the social conditions necessary for equality, while Ambedkar’s institutional safeguards provide necessary protections against majoritarian oppression. [32][34]

Their clash of civilizational visions ultimately enriched Indian democracy by ensuring that questions of social justice, individual rights, and collective identity remain at the center of political discourse. The continuing tension between their approaches reflects the ongoing challenge of building an inclusive society that honors both individual dignity and collective identity, a challenge that extends far beyond India’s borders to inform global discussions about equality, democracy, and social transformation. [36][34]

- https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/gandhi-vs-ambedkar/

- https://www.cvs.edu.in/upload/Ambedkar Gandhi Debate.pdf

- https://www.clearias.com/gandhi-and-ambedkar/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/great-debate-br-ambedkar-mahatma-gandhi-caste-sahil-sajad-ac6cc

- https://www.journalijar.com/uploads/2025/06/68660ae25341b_IJAR-52445.pdf

- https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/gandhi-and-ambedkar

- https://www.rammadhav.in/articles/babasahebs-conversion/

- https://cle.ens-lyon.fr/anglais/litterature/litterature-postcoloniale/gandhi-s-and-ambedkar-s-views-on-caste-the-representation-of-historical-figures-in-arundhati-roy-s-the-doctor-and-the-saint

- https://philosophy.institute/gandhian-philosophy/gandhis-interpretation-varna-system-social-harmony/

- https://philosophy.institute/gandhian-philosophy/rethinking-social-stratification-gandhi-vision/

- https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/Gandhi-on-moral-basis-on-hinduism.php

- https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/Gandhi-on-varnashram-system.php

- https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/Gandhi-Ambedkar-and-eradication-of-Untouchability.html

- https://compass.rauias.com/modern-history/harijan-campaign-gandhi/

- https://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/mmt/ambedkar/web/appendix_1.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annihilation_of_Caste

- https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/dhammachakra-pravartan-day-the-psychological-impact-of-conversion/

- https://www.thequint.com/news/india/br-ambedkar-conversion-to-buddhism

- https://drambedkarbooks.com/2015/11/20/why-dr-ambedkar-renounced-hinduism/

- https://www.constitutionofindia.net/historical-constitution/poona-pact-1932-b-r-ambedkar-and-m-k-gandhi/

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-news-editorials/poona-pact-1932

- https://www.studocu.com/in/document/jawaharlal-nehru-university/modern-indian-political-thought/thoughts-of-ambedkar-on-constitutional-democracy/28630472

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-analysis/democratic-vision-of-ambedkar

- https://www.ijrrssonline.in/HTML_Papers/International Journal of Reviews and Research in Social Sciences__PID__2024-12-4-4.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poona_Pact

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Poona-Pact

- https://www.allaboutambedkaronline.com/post/a-note-on-gandhi-and-his-fast

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-two_vows_of_Ambedkar

- https://www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2409194.pdf

- https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2025/07/14/ambedkars-constitutionalism-after-75-years/

- https://countercurrents.org/2021/10/gandhi-vs-ambedkar-debates-and-search-for-real-swaraj/

- https://navjyot.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/61.pdf

- https://www.indiatoday.in/history-of-it/story/ambedkar-gandhi-caste-system-poona-pact-1932-reservation-2445208-2023-10-06

- https://lawfullegal.in/ambedkar-and-gandhian-concepts-of-equality-a-comparative-study-and-contemporary-relevance/

- https://www.drishtiias.com/mains-practice-question/question-7804

- https://indianhistorycollective.com/ambedkar-warns-against-india-being-a-democracy-in-form-dictatorship-in-fact/

- https://www.scribd.com/document/488045998/322215128-Ambedkar-Annihilation-of-Caste

- https://library.bjp.org/jspui/handle/123456789/321

- https://www.journalofpoliticalscience.com/uploads/archives/7-6-44-367.pdf

- https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.71655

- https://testbook.com/question-answer/poona-pact-1932-was-signed-between-________–5e0aff9d72a2a90d02bd9b5f

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/ambedkar/2015.71655.Annihilation-Of-Caste-With-A-Reply-To-Mhatma-Gandhi.pdf

- https://gandhipedia150.in/static/data/highlighted_pdfs_output/Rajkot_volume54_book_383.pdf

- https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR1807747.pdf

- https://scroll.in/article/892922/shaming-the-hindus-gandhis-anti-untouchability-tour-of-1933-34

- https://uppcsmagazine.com/evaluation-of-gandhis-views-on-the-varna-system/

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Round-Table-Conference

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Round_Table_Conferences_(India)

- https://www.dailypioneer.com/2025/columnists/gandhi—s-morality-and-ambedkar—s-modernity.html

- https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/round-table-conference/

- https://prepp.in/news/e-492-third-round-table-conference-nov-17-dec-24-1932-modern-india-history-notes

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234668651.pdf

- https://namibian-studies.com/index.php/JNS/article/view/4561

- https://byjus.com/social-science/poona-pact/

- https://www.drishtiias.com/sambhav-daily-answer-writing-practice/papers/sambhav-2024/the-ideological-differences-between-gandhi-and-ambedkar-concerning-the-methods-for-achieving-societal-change/print

- https://www.granthaalayahpublication.org/Arts-Journal/ShodhKosh/article/download/2381/2126/16987

- https://www.hijlicollege.ac.in/lms/Sociology/2nd_Sem/gandhi and ambedkar.pdf

- https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/Gandhi-Ambedkar-and-eradication-of-Untouchability.php

- https://www.journalofpoliticalscience.com/uploads/archives/7-8-39-918.pdf

- https://www.socialsciencejournal.in/assets/archives/2025/vol11issue4/11078.pdf

- https://anubooks.com/uploads/session_pdf/16625312643.pdf