The Forge of Folly: Solidification, Institutionalization, and the Enduring Legacy of the ‘Martial Race’ Doctrine in British India (1858-1900)

I. The Crucible of 1857: A System of Loyalty and Disloyalty

The doctrine of “martial races,” a cornerstone of British military policy in India for nearly a century, was not a sudden invention but a direct consequence of the catastrophic Indian Rebellion of 1857. Prior to this pivotal event, the East India Company’s military establishment was a varied force, its composition often reflecting regional demographics. The largest of these, the Bengal Army, was primarily composed of dominant-caste Hindu sepoys, a structure that had evolved with a degree of accommodation for their caste privileges.1 The Bombay Army, in contrast, was notably more inclusive, with soldiers from the Mahar community, a group with a long and distinguished military history in the region, making up a significant portion—between 20 and 25 percent—of its ranks.3

The widespread uprising that began in 1857 was fueled by deep-seated Indian grievances, including burdensome taxation, new land policies that displaced traditional landowners, and a profound fear of forced conversion to Christianity, epitomized by the infamous greased cartridges rumor.2 The British, whose rule was nearly extinguished, were not saved by their own scattered forces alone but by the loyalty of other Indian communities. Crucially, the Madras and Bombay armies remained largely unaffected, while Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims, and Gurkhas actively sided with the British to suppress the rebellion.1

The British did not interpret this outcome as a matter of simple circumstance. Instead, they constructed a narrative to rationalize their near-defeat and re-legitimize their control. They concluded, through a politically motivated and highly selective analysis, that the uprising was a result of the “unreliability” of the dominant-caste, politically aware, and often urbanized populations of the Bengal and Awadh regions. Conversely, the loyalty of the Sikhs, Gurkhas, and others was attributed to their supposedly innate, atavistic “warlike qualities”.5 This new intellectual framework allowed the British to pathologize the mutineers as “cowards whose virility had wilted” and justify a radical reorganization of their military as both a scientific and pragmatic measure.5

Following the rebellion, the British dissolved the East India Company and established the British Raj.5 The military was completely overhauled, with a new focus on recruiting from communities that had proven their loyalty. This policy led to a profound shift in the army’s regional composition, a process often referred to as the “Punjabisation” of the army.6 The Gurkhas, Sikhs, and Punjabi Muslims were elevated to the status of “chivalrous heroes,” becoming the new pillars of the empire’s military strength.5

The profound shift in military composition and policy after 1857 is starkly illustrated in the following table.

| Military Class / Community | Pre-1857 Recruitment (Approximate) | Post-1857 Recruitment (Approximate) | Policy Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant-Caste Hindus | High proportion in Bengal Army (e.g., Brahmins, Rajputs) 1 | Systematically excluded; seen as disloyal and dangerous 6 | “Non-martial race” |

| Mahars | 20-25% of the British Bombay Army 3 | Systematically excluded; demobilized by 1892 3 | “Non-martial race” |

| Sikhs, Gurkhas, & Punjabi Muslims | Supported British, but not dominant 1 | Heavy recruitment; elevated to “chivalrous heroes” 4 | “Martial race” |

| Bengalis | Politicized middle class seen as dangerous 6 | Systematically excluded; mocked for “effeminate character” 5 | “Non-martial race” |

II. The Formalization of Doctrine: Codifying the ‘Martial Race’ (1858-1900)

In the decades following the rebellion, the ad-hoc recruitment preferences of the British were formalized into a coherent, though often contradictory, military doctrine.8 The martial race theory was a political and social construct, relying on a combination of racial, social, and religious criteria to classify populations.6 At its core was the belief that certain ethnic, religious, or caste groups possessed a more masculine character and an innate loyalty to the British Crown, making them uniquely suited for military service.6

This doctrine was not merely an administrative tool; it also functioned to redefine British identity in a post-mutiny world. The British, facing a crisis of confidence, reasserted their own martial identity by projecting an idealized, “virile” masculinity onto their chosen Indian subjects.5 The “chivalrous” Gurkhas, Sikhs, and Rajputs, with their supposed “Aryan ancestry” and noble, warlike qualities, became a kind of colonial mirror for the British officer’s self-image.5 This narrative was buttressed by an intentional campaign to denigrate nationalist and educated Indian populations, such as the urbanized Bengalis, who were dismissed as “effeminate” and “precious,” their lack of perceived virility becoming a convenient pretext for their political unreliability.5 This created a powerful and self-serving binary that legitimized both British rule and British national identity in the wake of a traumatic event.

The systematization of these ideas is often credited to Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of India from 1885-1893, who is frequently portrayed as the “father figure” of the theory.8 He took the disparate, pre-existing strands of thought and publicized them as a formal basis for recruitment.8 The policy was then firmly cemented into the military’s institutional fabric by Lord Kitchener’s reforms in 1903. While Kitchener’s reforms were presented as a move to transform the army from a constabulary to a modern fighting force, they fundamentally accepted and codified the martial race doctrine as the primary principle for recruitment and organization.9 This marked a critical shift from a preference to a foundational institutional principle.

The “divide and rule” aspect of the doctrine was not simply a diplomatic tactic; it was woven into the very structure of the military. By creating a system of “class regiments” or “class companies” 3, where specific units were composed of men from a single “class,” caste, or religion, the British fostered a strong internal solidarity within each unit while simultaneously reinforcing the social and religious divisions that formed the doctrine’s basis.11 This institutional design created a powerful, self-perpetuating mechanism of control. The British used some Indian populations to maintain order and quell dissent among others, a strategy that went beyond a simple policy and became a long-term, foundational principle of the Indian Army’s organization.5

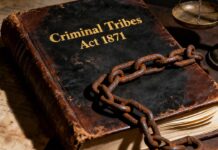

III. The Ethnographic State: Codification of Caste (1871-1931)

The institutionalization of the martial race doctrine was enabled and reinforced by a broader colonial project of knowledge production. Beginning with the first modern, decennial census in 1871, the British undertook to “know” India in order to “rule” it more effectively.12 This initiative transformed the fluid, decentralized, and highly localized social structures of jatis into rigid, administrative categories of “caste”.12 This was not a mere academic exercise. The census classifications became a direct tool of governance, used to distribute rights, formulate land taxes, and determine which groups were qualified for government jobs and appointments.12

Two of the leading “official anthropologists” of the era, Denzil Ibbetson and Herbert Risley, were instrumental in this process of classification.13 They operated under the foundational assumption that caste was a “concrete and measurable” entity with “definable characteristics—endogamy, commensality rules, fixed occupations”.13 Risley, a noted proponent of “race science,” used physical measurements, such as the ratio of a nose’s width to its height, to divide Indians into “Aryan” and “Dravidian” races, which he then linked directly to the caste hierarchy.14 Ibbetson, though more nuanced, similarly created a hierarchical classification of tribes and “menial castes” in his foundational census reports.16

This ethnographic work provided a “scientific” pretext for the military’s discriminatory recruitment policies. The British assumed that the traditional Kshatriya (warrior) caste, from the ancient Vedic social system, were the direct ancestors of the “martial races” they favored, such as the Rajputs.8 This linkage provided a historical justification for a contemporary policy of exclusion. The doctrine was also used to exclude the “educated populace,” particularly Bengalis, who were seen as a “dangerous” and “politicized middle class” and thus unfit for military service.6

The colonial administration established a self-reinforcing system of control. The census and ethnographic surveys provided the “data” to justify the military’s exclusionary policies, and the military, in turn, reinforced the social classifications by granting prestige, land, and economic opportunities to “martial” groups while denying them to “non-martial” ones. This created a synergistic feedback loop of colonial power: the state produced knowledge that legitimized its discriminatory policies, and those policies then reinforced the social divisions the knowledge had created. The infamous Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, which targeted “low castes and inferior races” and labeled entire groups as “criminal by birth,” further demonstrates how these legal, administrative, and military systems worked in tandem to control and marginalize “unreliable” populations.8

IV. The World Wars: A Doctrine Under Strain (1914-1945)

For all its supposed rigidity and scientific basis, the martial race doctrine proved to be a flexible instrument when faced with the immense pressures of two global conflicts. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 created an unprecedented and immediate demand for military manpower.8 The Indian Army, which began the war with a modest force of just over 159,000 men, ultimately recruited approximately 1.5 million combatants and non-combatants over the course of the conflict.18

This exponential demand forced the British to pragmatically modify the martial race theory.8 Recruitment was expanded beyond the traditional regions of Punjab, the North-West Frontier, and Nepal to include new groups from Rajputana and Central India.6 This demonstrates that the doctrine was not a rigid, immutable scientific law, but a flexible political tool that could be adapted to meet imperial needs. However, despite the expansion of recruitment, the bulk of the army still came from the traditional martial races.8 This adherence to core principles, even under duress, proves that the ideology, while not static, remained deeply ingrained.

The Second World War saw an even more dramatic expansion. The Indian Army grew to a force of over 2.5 million men by August 1945, becoming the largest volunteer army in history.19 This scale of recruitment forced the British to tap into previously excluded “non-martial races,” particularly from South India.20 The most striking example of this pragmatic shift was the formation of the Chamar Regiment in 1943.21 This unit, which was raised from a community classified as “low caste” and “non-martial,” fought with distinction against the Japanese in Burma and was awarded the Battle Honor of Kohima.21

A fundamental hypocrisy underlies this wartime pragmatism. While the British were forced to recruit from “non-martial” communities, their propaganda continued to emphasize the loyalty and valor of the “martial races”.20 Photographic collections from 1942, for instance, often excluded images of Sikh recruits and focused on so-called “Madrasi” troops from the south, but without the “ethnographic attention” and symbolic prestige reserved for their northern counterparts.20 This reveals that while the British needed the manpower from these communities, they were unwilling to grant them the same symbolic legitimacy or fully integrate them into the preferred colonial narrative of a “martial” army. The doctrine was bent to meet an existential crisis but was never broken.

V. Erasure as a Tool of Power: A Case Study of Mahar, Chamar, and Jatav Histories

The British classification of “martial” and “non-martial” was not a reflection of reality but a political construction designed to consolidate power and control. A closer examination of the military histories of communities branded as “non-martial” reveals a deliberate and purposeful act of historical erasure. The Mahar community, for instance, had a celebrated martial tradition that predated the British, serving the Maratha king Shivaji and comprising a significant portion of the British Bombay Army from the 1750s.3 Their bravery was praised by British officers, and their sacrifice at the Battle of Koregaon is memorialized on the Koregaon pillar.3

Despite this history of valor and loyalty, the Mahars were systematically demobilized in 1892 when the British instituted “class regiments” that excluded them.3 This was not an accident or a simple oversight. It was a calculated political act. The reason given for their exclusion was the new emphasis on “class regiments” 3, but the underlying motivation was to weed out communities deemed “unreliable” and potentially politicized after the 1857 mutiny.3 The demobilization was regarded by the Mahars as a “betrayal of their loyalty”.3 This demonstrates that the British were not simply selecting for “martial qualities,” but were actively erasing the military history of communities they feared would become a threat to their rule.

Similarly, the British classified the Chamar and Jatav communities as “non-martial” and “low caste”.8 However, their historical record contradicts this narrative entirely. The Satnami revolt of 1672 against the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb was led by a sect composed largely of downtrodden-caste groups, including leather workers, who inflicted several defeats on the Mughal forces and established their own administration.22 Furthermore, members of these communities, such as Banke Chamar and Chetram Jatav, actively participated in the 1857 rebellion, directly challenging the British narrative of their “disloyalty”.22

In the early 20th century, the Jatavs demonstrated a profound political awakening by directly challenging the British’s classificatory system. They actively sought to improve their social status by claiming a Kshatriya (warrior) ancestry and successfully petitioned the British to be classified as ‘Jatav’ instead of ‘Chamar’ in the 1931 census.23 This campaign demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of how the colonial state was using knowledge (the census) as a tool of control. The Jatavs fought back by using the same system to assert their historical identity, proving that the British classification was a tool of power, not a reflection of reality.

VI. Post-War Transition and Enduring Legacy

The legacy of the martial race doctrine did not end with the departure of the British. Following the partition of British India in 1947, the military establishment was divided between the newly independent nations of India and Pakistan.25 The Indian government, in a move to build an egalitarian and national military, formally abolished the official application of “martial race” principles in recruitment in February 1949.17

However, despite this formal repeal, the unacknowledged legacy of the doctrine persists in the modern Indian Army’s composition. The Indian government inherited not just a military but a deeply ingrained institutional culture and a regimental system built on the colonial “class composition” model.11 While the official ideology of the modern army is egalitarian, the social and regional recruitment networks established over a century of colonial rule continue to create a de facto over-representation of certain groups.

The following table demonstrates this enduring effect.

| Regiment Name | Composition | Colonial-Era Designation | Post-Independence Expansion (1947-1970s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Punjab Regiment | Sikhs, Dogras | “Martial Race” 17 | Expanded from five to 29 battalions 17 |

| Rajputana Rifles | Jats, Rajputs | “Martial Race” 17 | Expanded from six to 21 battalions 17 |

| President’s Bodyguard | Exclusively Sikhs, Jats, and Rajputs | “Martial Race” 17 | Explicit ethnic requirements persist 17 |

The existence of an over-representation of certain groups, such as the Sikhs, Jats, and Rajputs, is not accidental; it is a direct result of a century of deliberate colonial policy.17 The Punjab Regiment and Rajputana Rifles, for example, have seen a massive expansion in battalions since independence and remain over-represented in the army’s headcount.17 The President’s Bodyguard, a ceremonial unit, still has explicit ethnic requirements, a vestige of the colonial-era regimental system.17 This highlights a central paradox of post-colonial nation-building: how does a new state overcome institutional structures that were designed to be exclusionary, even when the formal policies that created them have been discarded? The persistence of these recruitment patterns demonstrates that the martial race doctrine, though formally dead, remains a powerful, unacknowledged force in shaping the institutional and social fabric of the modern Indian Army.

Works cited

- Why did the Indian Mutiny happen? | National Army Museum, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/why-did-indian-mutiny-happen

- Causes of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_the_Indian_Rebellion_of_1857

- Mahar Regiment – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahar_Regiment

- 1857 Indian Uprising – OER Project, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.oerproject.com/en/oer-materials/oer-media/html-articles/origins/unit7/1857-indian-uprising

- Martial Races | EHNE, accessed September 11, 2025, https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/gender-and-europe/european-man-a-hegemonic-masculinity-19th-21st-centuries/martial-races

- Martial Races, Theory of – 1914-1918 Online, accessed September 11, 2025, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/martial-races-theory-of-1-1/

- Martial Races, Theory of – 1914-1918 Online, accessed September 11, 2025, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/martial-races-theory-of-1-1/?format=pdf

- Race and Recruitment in the Indian Army: 1880–1918* | Modern …, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/modern-asian-studies/article/race-and-recruitment-in-the-indian-army-18801918/054587B97D07557F48A4CEAC7553D0AC

- [Autom. eng. transl.] From the Indian Army to the Army of India. The Kitchener reform (1903) and the modernization of the British Indian military device – PubliRES, accessed September 11, 2025, https://publires.unicatt.it/en/publications/dallindian-army-allarmy-of-india-la-riforma-kitchener-1903-e-la-m-7

- The Untouchable Soldier: Caste, Politics, and the Indian Army | The Journal of Asian Studies, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-asian-studies/article/untouchable-soldier-caste-politics-and-the-indian-army/3CFBA8546235C6D0328757C437ADD34F

- Indian Army (Class Composition) – Hansard – UK Parliament, accessed September 11, 2025, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1932-05-26/debates/7a7c7487-3f22-4313-8d5d-80ab194f91a2/IndianArmy(ClassComposition)

- Lecture 4: Colonial societies, state formation and comparative development (India, China, Japan) – Thomas Piketty, accessed September 11, 2025, http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/PikettyEconHist2023Lecture4.pdf

- Anthropologists and Viceroys: Colonial knowledge and policy making in India, 1871–1911* | Modern Asian Studies | Cambridge Core, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/modern-asian-studies/article/anthropologists-and-viceroys-colonial-knowledge-and-policy-making-in-india-18711911/F1176F90556A70AF2178AB813DE051CF

- Caste system in India – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caste_system_in_India

- Colonial Ethnography and Theories of Caste in Late‑Nineteenth‑Century India – Bérose, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.berose.fr/article2793.html

- Anthropologists and Viceroys: Colonial knowledge and policy making in India, 1871–1911 – Cambridge University Press & Assessment, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/F1176F90556A70AF2178AB813DE051CF/S0026749X15000037a.pdf/anthropologists_and_viceroys_colonial_knowledge_and_policy_making_in_india_18711911.pdf

- Martial race – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martial_race

- Military Planning and Wartime Recruitment (India) – 1914-1918 Online, accessed September 11, 2025, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/military-planning-and-wartime-recruitment-india/

- Indian Army during World War II – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Army_during_World_War_II

- Anxieties and Absences: What a photographic collection depicting the recruitment of Indian soldiers tells us about the British Indian Army in 1942 | Imperial War Museums, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.iwm.org.uk/research/research-projects/provisional-semantics/anxieties-and-absences

- Chamar Regiment – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chamar_Regiment

- Military History | The Ravidassia Community – WordPress.com, accessed September 11, 2025, https://ravidassia.wordpress.com/chamars-in-the-military/

- Jatav – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jatav

- Jatav Mahasabha – Wikipedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jatav_Mahasabha

- How did India and Pakistan organize armed forces after 1947? : r …, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/IndianHistory/comments/1klah5j/how_did_india_and_pakistan_organize_armed_forces/