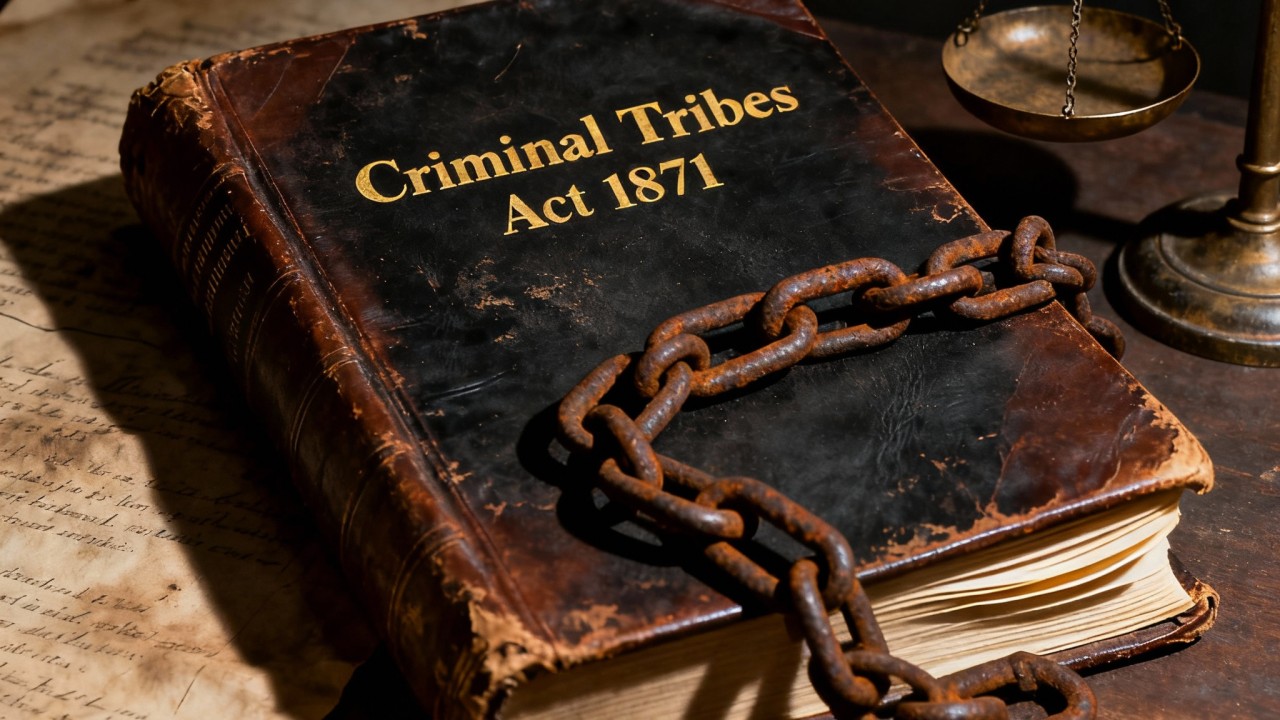

The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871: A Dark Chapter in Colonial Legal History

The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 represents one of the most draconian and discriminatory pieces of legislation enacted during British colonial rule in India. This Act fundamentally altered the legal landscape by introducing the unprecedented concept of hereditary criminality, branding entire communities as “born criminals” and subjecting millions of Indians to systematic surveillance, forced settlement, and social ostracization. At the time of Indian independence in 1947, thirteen million people across 127 communities remained under the shadow of this colonial law. The Act’s legacy extends far beyond its formal repeal in 1949, as denotified tribes continue to face discrimination and marginalization in contemporary India, highlighting the enduring impact of colonial legal frameworks on post-independence society.[1][2]

Historical Context and Origins

Pre-Colonial Background and Caste Hierarchies

The foundations of the Criminal Tribes Act can be traced to ancient Indian social hierarchies that were later exploited and rigidified by colonial administrators. Ancient religious texts from the Rigveda to the Manusmriti had established caste-based distinctions that created social stratification in Indian society. However, the British colonial administration transformed these traditional social categories into administrative tools for control and governance. The colonial interpretation of Indian society as inherently lawless provided the ideological justification for extraordinary legal measures. A member of the British Viceroy’s Council observed in the 1860s that India was a nation “singularly void of law,” deliberately overlooking the complex traditional legal systems that had governed Indian communities for centuries. [1][3][4]

The Thuggee Precedent

The immediate legal precedent for the Criminal Tribes Act emerged from the British campaign against thuggee in the 1830s. The Thuggee and Dacoity Suppression Acts of 1836-48 established the revolutionary legal principle of collective criminality, allowing individuals to be convicted based solely on group affiliation without evidence of personal criminal activity. Major General William H. Sleeman led this campaign, developing extensive knowledge of what the British characterized as an organized criminal system. The suppression of thuggee created a legal framework that presumed hereditary criminal tendencies within specific groups, setting the stage for the broader application of this principle under the Criminal Tribes Act. [5][6][7][8][9][10]

Aftermath of the 1857 Revolt

The Criminal Tribes Act originated as a direct response to the aftermath of the 1857 revolt, where many tribal chiefs were labeled as traitors and considered rebellious. The revolt had exposed the vulnerability of British control over nomadic and semi-nomadic populations who could mobilize quickly and evade traditional surveillance methods. Colonial administrators viewed these mobile communities as inherently threatening to the stability of British rule. The Act thus served multiple purposes: suppressing potential sources of rebellion, facilitating taxation and administrative control, and implementing social engineering projects designed to transform Indian society according to British colonial visions. [3][11][12][13]

Timeline of the Criminal Tribes Act from Colonial Enactment to Post-Independence Repeal (1871-1952)

Legal Framework and Provisions

Core Legislative Structure

The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 was enacted on October 12, 1871, receiving the assent of the Governor General. The Act contained six distinctive features that set it apart from ordinary criminal law. First, it operated above normal penal law, prescribing restrictions and punishments for acts that typically did not constitute criminal offenses under standard legal frameworks. Second, it applied to entire tribes, gangs, or classes of persons that local governments claimed were “addicted to the systematic commission of non-bailable offences”. This sweeping application meant that individual innocence or guilt became irrelevant; membership in a designated group alone was sufficient for legal restrictions. [14][11][15]

Notification and Surveillance Mechanisms

Under Section 3 of the Act, local authorities possessed the power to label any group with a “systematic addiction to committing crimes not punishable by bail” as a criminal tribe. Once notified, these communities faced comprehensive surveillance measures including mandatory roll calls, restricted movement through a passport system, and various other legal disabilities. The Act established that “every such notification shall be conclusive proof that the provisions of this Act are applicable to the tribe, gang or class specified therein,” eliminating any possibility of legal challenge or judicial review. This provision effectively placed affected communities outside the protection of normal legal procedures. [14][3]

Registration and Movement Control

The Act mandated extensive registration requirements for all adult male members of notified tribes. Section 10(1)(a) required village police stations or panchayats to maintain registers containing names, left thumb impressions, and ages of all adult males in each household, including children and dependents. Every registered member was compelled to report to police or village administration either weekly or as required by the District Magistrate, severely limiting their freedom of movement and right to privacy. Any registered member who changed residence was required to immediately inform the village headman of both their permanent and temporary addresses, with all changes recorded in the village registry. [3]

Reformatory Settlements and Forced Labor

Section 6 of the Act empowered the government to establish special “reformatory settlements” for criminal tribe members, which functioned as forced relocation centers. Entire families were rounded up and transported to distant, isolated sites that operated like open prisons. Within these settlements, people were forced into labor under the guise of reform through industrial or agricultural work. In the Madras Presidency, members of notified tribes were herded into facilities like the Yerawada reformatory, where they worked under constant surveillance while being denied basic freedoms. These settlements served the dual purpose of containing perceived threats while providing cheap labor for colonial enterprises. [4][16]

Implementation and Expansion

Geographic Extension

The Criminal Tribes Act was initially implemented in the northern regions of British India before being systematically extended across the subcontinent. The Act was extended to Bengal in 1876 and gradually expanded to other areas, with the Madras Presidency becoming the last to implement it in 1911. This phased expansion allowed colonial administrators to refine their methods and develop increasingly sophisticated systems of surveillance and control. By 1924, the Act had been implemented across most of colonial India through a series of amendments and consolidations that expanded its scope and severity.[3][2][17]

Administrative Implementation

Local officials, including village headmen and police officers, were granted extensive discretionary powers in determining which individuals and communities should be subject to the Act’s provisions. The regulation required local officials to compile comprehensive lists of every person classified as belonging to a criminal tribe within their jurisdiction. Once an individual’s name appeared on such a list, there was no legal mechanism for removal, creating permanent classifications that passed from generation to generation. The Act specifically prohibited legal challenges to an official’s determinations, eliminating even symbolic checks and balances on administrative power. [3]

Community Targeting and Scope

By its peak implementation, the Criminal Tribes Act affected hundreds of communities across India. The colonial government listed 237 criminal castes and tribes under the Act in the Madras Presidency alone by 1931. Initially targeting groups like Gujjars, Harni (a sub-clan of Rajput), and Lodhi communities, the Act’s enforcement expanded by the late 19th century to include most Shudras and “untouchables” such as Chamars, as well as Sanyasis and hill tribes. The Act also specifically targeted transgender communities, with the 1897 amendment adding eunuchs to its scope and ordering that “criminal” eunuchs “dressed or ornamented like a woman in a public street… be arrested without warrant” and imprisoned. [18][11][19][2]

| Community/Tribe | Region/State | Traditional Occupation | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gujjars | North India (Punjab, Haryana) | Pastoralism, Trading | Denotified – mostly OBC |

| Chamars | North India (UP, Bihar) | Leatherwork, Agriculture | Denotified – SC |

| Sansis | Punjab, Haryana | Trading, Performance | Denotified – OBC |

| Bhils | Central India (MP, Gujarat) | Agriculture, Forest Work | Mostly ST |

| Pardhis | Central India (MP, Maharashtra) | Hunting, Gathering | Denotified – struggling |

| Banjaras/Lambadas | South India (Karnataka, Telangana) | Trading, Cattle Rearing | Denotified – ST/OBC |

| Narikuravars | Tamil Nadu | Beadwork, Street Vending | Denotified – no ST status |

| Ahirs | North India (Rajasthan, UP) | Pastoralism | Denotified – OBC |

| Lodhi | Central India (MP, UP) | Agriculture, Trading | Denotified – OBC |

| Sanyasis | Across India | Religious Mendicancy | Denotified |

| Domes | Bengal | Scavenging, Manual Labor | Denotified – SC |

| Rebari | Rajasthan, Gujarat | Pastoralism | Denotified – OBC |

| Bhar | North India | Agriculture | Denotified |

| Pasi | North India | Agriculture, Labor | Denotified – SC |

| Yerukula | South India | Basket Making | Denotified |

| Bedia | Central India | Folk Performance | Denotified – struggling |

| Chharas | Gujarat | Street Performance | Denotified – ongoing stigma |

| Kanjars | North India | Trading | Denotified |

| Tadvis | Central India | Labor | Denotified |

| Nat | Across India | Performance, Acrobatics | Denotified |

| Irula | South India | Snake Catching | Denotified |

| Bowreah | Bengal | Trading | Denotified |

| Budducks | Bengal | Labor | Denotified |

| Bedyas | Bengal | Labor | Denotified |

Impact on Affected Communities

Social Stigmatization and Marginalization

The designation as “criminal tribes” created an indelible mark of social stigma that extended far beyond legal restrictions. The very label became what contemporary observers described as a “mark of Cain,” leading to intensified social ostracization from wider society. Dominant-caste and non-notified neighbors viewed these communities with increased suspicion and contempt, knowing that the government itself had classified them as hereditary criminals. British missionaries writing in the 1880s observed that even when members of criminal tribes attempted to settle and live honestly, villagers refused to accept them, referring to them derisively as “CTA-wallahs” and often barring them from accessing common resources.[4]

Economic Disruption and Impoverishment

The Act’s movement restrictions devastated the economic foundations of many affected communities, particularly those dependent on nomadic trade and seasonal migration. The Lambada/Banjara people, traditional caravan traders, lost their extensive trade networks when mobility was curtailed and were forced into settlements where meaningful work was scarce. Similarly, the Sansis of Punjab, who had sustained themselves through performance and petty trading, were relocated to reformatory settlements and reduced to manual labor under colonial supervision. Many communities possessed minimal land ownership due to pre-existing caste discrimination, and whatever lands or possessions they had were often confiscated during forced relocations.[4]

Loss of Cultural Identity and Traditional Practices

The forced settlement of nomadic communities resulted in the systematic destruction of cultural practices and traditional knowledge systems. Communities that had maintained oral traditions, seasonal festivals, and specialized crafts for generations found their cultural transmission disrupted by surveillance requirements and geographical confinement. Children were frequently separated from their families and placed in reformatory institutions, breaking the intergenerational transfer of cultural knowledge and traditional skills. The Act’s emphasis on transforming these communities into “productive” laborers according to colonial definitions fundamentally altered their relationship with traditional occupations and cultural practices. [11][2]

Physical Hardships and Human Rights Violations

The reformatory settlements established under the Act subjected residents to harsh physical conditions and systematic human rights abuses. The British government established special settlements where people were “imprisoned, shackled, caned and flagellated while being encompassed by high walls”. Adult males were required to report weekly to police stations, while entire families faced constant surveillance and could be arrested without warrant for any perceived violation of movement restrictions. The psychological impact of living under permanent suspicion and surveillance created lasting trauma that affected multiple generations within affected communities. [3][18][20]

Legal and Constitutional Challenges

Absence of Due Process

The Criminal Tribes Act operated outside established principles of due process and natural justice by eliminating fundamental legal protections. The Act’s provision that notification of a group as criminal constituted “conclusive proof” meant that affected individuals had no recourse to judicial review or legal challenge. This extraordinary departure from established legal norms meant that entire communities could be subjected to severe restrictions without any opportunity to contest their classification or seek redress through normal legal channels. The Act thus created a parallel legal system that bypassed constitutional protections and established precedents for administrative detention and collective punishment. [14]

Violation of Individual Rights

The presumption of hereditary criminality fundamentally violated principles of individual responsibility and personal autonomy that formed the basis of modern legal systems. By treating criminal tendency as an inherited characteristic, the Act denied the possibility of individual reform or choice, creating a deterministic view of human behavior that contradicted evolving understanding of criminal justice. The weekly reporting requirements, movement restrictions, and surveillance measures violated basic freedoms of association, movement, and privacy that were increasingly recognized as fundamental human rights in legal systems worldwide. [15][13]

Colonial Legal Innovation

The Act represented a significant innovation in colonial legal strategy by creating a framework for permanent surveillance and control that extended far beyond traditional criminal law. Unlike conventional criminal legislation that responded to specific acts, the Criminal Tribes Act sought to prevent potential crimes by controlling entire populations deemed inherently dangerous. This preventive approach to criminal justice established precedents that would influence policing strategies and security legislation throughout the colonial period and beyond.[3]

Resistance and Opposition

Community Responses

Despite severe restrictions and surveillance, many affected communities developed strategies of resistance and adaptation to colonial control. Some groups attempted to petition colonial authorities for removal from criminal tribe lists, though the Act’s provisions made such appeals legally impossible. Others sought to modify their traditional practices to avoid surveillance while maintaining cultural identity. The complexity of these responses demonstrates the agency retained by affected communities even under systematic oppression. [3]

Early Reform Movements

By the 1930s and 1940s, growing awareness of the Act’s injustices led to increased criticism from Indian political leaders and social reformers. The Criminal Tribes Act Enquiry Committee appointed by the Bombay Government in 1937 recommended significant dilution of the Act’s punitive elements, recognizing that the legislation had failed to achieve its stated objectives while causing enormous social harm. These official acknowledgments of the Act’s failures provided important groundwork for its eventual repeal. [14]

International Critique

The concept of hereditary criminality embodied in the Criminal Tribes Act increasingly came under international scrutiny as global understanding of human rights and individual dignity evolved. The Act’s presumption of inherited criminal tendencies contradicted emerging international legal principles and scientific understanding of human behavior, making it difficult to defend even within colonial administrative circles.

Repeal and Aftermath

The Path to Repeal

The Criminal Tribes Act was finally repealed in August 1949, following recommendations from the Criminal Tribes Enquiry Committee Report of 1949-50. The newly independent Indian government recognized that the Act was fundamentally incompatible with constitutional principles of equality and individual rights. The formal repeal process involved “denotifying” all previously classified criminal tribes, officially removing their legal designation as hereditary criminals. However, the transition from colonial to post-colonial legal frameworks proved more complex than simply repealing discriminatory legislation. [21][17]

The Habitual Offenders Act of 1952

Despite the repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act, the Indian government soon introduced the Habitual Offenders Act of 1952, which continued to target many of the same communities under different legal terminology. While framed around individual behavior rather than group membership, the Habitual Offenders Act disproportionately affected denotified tribes and maintained many of the surveillance and control mechanisms of its predecessor. The Act asked police to investigate suspects’ “criminal tendencies” and whether their occupation was “conducive to settled way of life,” language that effectively continued colonial-era discrimination against nomadic and marginalized communities.[21][17][22]

Persistent Discrimination and Contemporary Challenges

More than seven decades after the repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act, denotified tribes continue to face systematic discrimination and marginalization. Many police training manuals still identify certain communities as suspects in crimes by default, perpetuating colonial-era prejudices in law enforcement practices. The social stigma attached to these communities persists, affecting their access to education, employment, healthcare, and government services. Contemporary challenges include lack of proper documentation and identity papers, limited access to education and healthcare, continued police harassment under habitual offender laws, and ongoing social ostracization based on historical stereotypes. [22][23][24][25]

Contemporary Relevance and Ongoing Issues

Current Legal Status and Rights

Today, there are 313 Nomadic Tribes and 198 Denotified Tribes in India who continue to face the legacy of colonial classification through continued alienation and stereotyping by policing and judicial systems. According to the National Commission for Denotified, Nomadic and Semi-Nomadic Tribes, there are 1,262 such communities across India. While most denotified tribes are spread across Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC) categories, some remain outside any reservation category, limiting their access to affirmative action benefits. [2][23][26]

Recent Legal Developments

In October 2024, the Supreme Court of India expressed serious concern over the continued use of habitual offender classifications, with then-Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud stating that “a whole community ought not to have either been declared a criminal tribe in the past or a habitual offender in the present”. The Court urged states to review the relevance and application of these laws, particularly when they function as tools for profiling entire communities. This intervention represents a significant judicial recognition of the ongoing discrimination faced by denotified tribes.[17][27]

International Perspectives

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) asked India to repeal the Habitual Offenders Act in 2007, recognizing it as a continuation of colonial-era discrimination. The National Human Rights Commission has repeatedly emphasized the importance of implementing recommendations from various committees studying denotified tribes, including the complete repeal of discriminatory legislation. These international and national human rights perspectives highlight the global significance of addressing the legacy of the Criminal Tribes Act. [21][26][28]

Socioeconomic Challenges

Contemporary denotified tribes face multiple intersecting challenges that reflect the enduring impact of colonial classification. With a population of around 110 million, these communities confront extraordinary levels of discrimination extending beyond documented stigma and persecution. Many continue to engage in traditional occupations like street vending, itinerant labor, and petty trading, often living in poverty due to limited access to education and formal employment opportunities. Landlessness remains a critical issue, with many communities forced to live on pavements or in insecure housing due to lack of land rights. [23][29]

Government Initiatives and Reform Efforts

Policy Interventions

The Indian government has launched several welfare schemes to address the socioeconomic challenges faced by denotified tribes. The SEED Scheme introduced in 2022 supports DNTs through education, employment, and entrepreneurship initiatives. Various scholarship programs, including the Dr. Ambedkar Pre-Matric and Post-Matric Scholarship schemes, have been designed to increase educational access for students from DNT, NT, and SNT backgrounds. Additionally, the government provides skill development programs and financial support for housing to create sustainable livelihoods for nomadic families. [22][24]

State-Level Initiatives

Different states have implemented targeted programs for specific denotified communities. Maharashtra provides special financial assistance and hostels for NT students, while Tamil Nadu offers scholarships for Narikuravars and other DNT students. Madhya Pradesh has established free housing and skill training programs for the Pardhi community, and Gujarat has developed rehabilitation programs for the Chharas community, formerly labeled as criminals. These state-level interventions demonstrate recognition of the specific challenges faced by different denotified communities. [22]

Institutional Mechanisms

The establishment of the National Commission for Denotified, Nomadic, and Semi-Nomadic Tribes (NCDNT) represents an important institutional mechanism for studying and addressing DNT issues. The commission works on categorization within SC/ST/OBC frameworks to ensure proper representation and has studied the socioeconomic conditions of these communities through various reports, including the Renke Commission (2008) and Idate Commission (2014). These institutional efforts provide frameworks for policy development and implementation of targeted interventions. [22][26]

Conclusion

The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 stands as one of the most egregious examples of discriminatory colonial legislation, demonstrating how legal frameworks can be weaponized to systematically oppress entire communities based on birth and social identity. The Act’s presumption of hereditary criminality violated fundamental principles of justice and individual rights while serving colonial administrative objectives of control and social engineering. Its impact extended far beyond legal restrictions, creating enduring social stigma and economic marginalization that continues to affect millions of Indians today.

The persistence of discrimination against denotified tribes more than seven decades after independence highlights the deep structural nature of colonial legacies and the inadequacy of formal legal reforms alone in addressing systemic injustice. The replacement of the Criminal Tribes Act with the Habitual Offenders Act demonstrates how discriminatory practices can be perpetuated through new legal frameworks while maintaining the appearance of reform. Contemporary challenges faced by denotified tribes—including police harassment, social ostracization, economic marginalization, and lack of access to basic services—reflect the enduring impact of colonial classification systems on post-independence Indian society.

The recent Supreme Court intervention questioning habitual offender laws and international calls for their repeal indicate growing recognition of the need for comprehensive legal and social reforms. However, addressing the legacy of the Criminal Tribes Act requires more than legislative changes; it demands fundamental transformation of social attitudes, policing practices, and institutional frameworks that continue to perpetuate colonial-era prejudices. The struggle of denotified tribes for dignity, equality, and justice represents a critical test of India’s commitment to constitutional principles and social justice, highlighting the ongoing relevance of historical injustices in contemporary legal and social discourse.

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5349605

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criminal_Tribes_Act

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/criminal-tribes-act-1871/

- https://oaskpublishers.com/assets/article-pdf/the-criminal-tribes-act-of-1871-and-its-global-legacy.pdf

- https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/corvette/article/view/17067/7283

- https://angusalive.scot/museums-galleries/world-cultures-collection/the-thuggee/

- https://www.csas.ed.ac.uk/sites/csas/files/assets/pdf/WP19_Tom_Lloyd.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thuggee_and_Dacoity_Suppression_Acts,_1836–48

- https://victorianweb.org/history/empire/india/thuggee.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thuggee

- https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/criminal-tribes-act-1871/

- https://stophindudvesha.org/tracing-the-roots-indias-dalit-problem-the-criminal-tribes-act-of-1871/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/IndianHistory/comments/1jgdo6p/why_do_you_think_the_british_colonial_government/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5414894/

- https://garudalife.in/the-criminal-tribes-act-1871-the-devious-law-that-turned-heroic-legends-into-born-criminals

- https://indianapublications.com/articles/IJAL_3(3)_27-31_63bffb03759c45.28431082.pdf

- https://vajiramandravi.com/current-affairs/indias-habitual-offender-laws-a-legacy-of-discrimination/

- https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criminal_Tribes_Act

- https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/criminal-tribe-act-1871

- https://ignited.in/index.php/jasrae/article/download/6359/12520/31277

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denotified_Tribes

- https://theuniqueacademy.com/news/5444/de-notified-tribes-in-india

- https://fortuneiascircle.com/backgrounder/denotified_tribes

- https://www.actionaidindia.org/the-stigma-and-challenge-of-having-no-fixed-address-rights-of-denotified-nomadic-and-semi-nomadic-tribes-in-india/

- https://idronline.org/article/rights/why-are-nt-dnt-tribes-struggling-to-establish-their-identity/

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-analysis/idate-commission-report

- https://www.civilsdaily.com/news/21st-march-2025-the-hindu-op-ed-how-do-habitual-offender-laws-discriminate/

- https://nhrc.nic.in/press-release/habitual-offenders-act-be-repealed-nhrc-takes-cause-denotified-and-nomadic-tribes

- https://www.ksgindia.com/blog/indias-denotified-tribes.html

- https://www.studocu.com/in/messages/question/7783198/list-main-provision-and-implications-of-criminal-tribe-act-1871-in-1000-words

- https://open.library.ubc.ca/media/stream/pdf/24/1.0390312/4

- https://nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/CRS_HR_Status_denotified_Nomadic_Communities_Delhi_Gujarat_Maharasthra_20042018.pdf

- https://www.actionaidindia.org/more-than-70-years-from-liberation-former-criminal-tribes-continue-to-endure-stigma-and-discrimination/

- https://sprf.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/SPRF-2022_DP_Criminalising-Tribes-Pt-1_Final-1.pdf

- https://www.indiacode.nic.in/repealedfileopen?rfilename=A1871-27.pdf

- https://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/mmt/ambedkar/web/readings/Simhadri.pdf

- https://www.shankariasparliament.com/current-affairs/considering-repeal-of-habitual-offenders-act-denotified-tribes

- https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/thugee-and-dacoit-suppression-acts-1836-48/

- http://indianculture.gov.in/digital-district-repository/district-repository/thuggee-and-dacoity-suppression-acts

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/5349605.pdf?abstractid=5349605&mirid=1

- https://nluassam.ac.in/docs/Journals/NLUALR/Volume-7/Article 12.pdf

- https://amoghavarshaiaskas.in/denotified-tribes-classification-a-step-towards-socialjustice/

- http://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/64016C83-7AF3-474F-A80F-F4468C5FCCC2.pdf

- https://www.shankariasparliament.com/current-affairs/state-of-denotified-tribes

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-analysis/challenges-and-developments-related-with-denotified-tribes

- http://www.commonlii.org/in/journals/NALSARLawRw/2011/11.pdf

- https://ppl-ai-code-interpreter-files.s3.amazonaws.com/web/direct-files/2b8c2a8ee976d56ffb6eb75a7823ca0d/a3d1c127-0c8d-42fa-b275-9d96de3d2125/d975f00f.csv