Black Resistance to White Supremacy and Strategic Lessons for India’s Downtrodden Communities: A Comparative Framework for Liberation

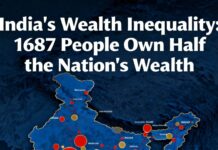

From the abolition struggles of the 1700s to the digital activism of the twenty-first century, Black Americans have waged a multifaceted, centuries-long resistance against the twin systems of white supremacy and racial capitalism. This resistance has evolved through distinct phases—from slave revolts and abolitionist organizing to mass-based civil rights campaigns, Black Power movements, and contemporary digital mobilization—each innovating new tactics while remaining rooted in fundamental demands for human dignity, economic justice, and self-determination. Simultaneously, in India, Downtrodden (Dalit), Adivasi, and Bahujan communities have engaged in parallel struggles against centuries of caste-based oppression and feudal exploitation, developing their own repertoires of resistance through legal mobilization, cultural assertion, grassroots organizing, and increasingly, digital activism. By examining these interconnected histories of resistance and drawing strategic parallels, marginalized communities in the Indian context can extract valuable lessons for coalition-building, policy reform, and reclaiming narrative control in their ongoing fights for justice and equality.[1][2][3]

Slavery-Era Abolitionism and the Genesis of Black Resistance: From Physical Defense to Political Mobilization

The Role of Free Black Communities and Early Organizing

The abolitionist movement was fundamentally animated by Black agency and intellectual leadership, despite historical narratives that centered white abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison. In the 1780s and beyond, free Black communities in the North organized independently, creating mutual aid societies, churches, and schools while simultaneously pushing white abolitionists toward more radical positions. By 1809, free Blacks had established an annual holiday commemorating the abolition of the international slave trade, asserting their own commemorative practices and historical narrative. In 1817, Black activists organized mass meetings to oppose the American Colonization Society, which sought to remove free Blacks from America and resettle them in Africa—a campaign that revealed how free Black communities understood the contradiction between racial oppression and national belonging.[1]

Free Black activists actively shaped the ideological direction of the antislavery movement. Their opposition to colonization and their emphasis on immediate emancipation influenced William Lloyd Garrison’s 1830 conversion to “immediatism,” the doctrine that slavery must be abolished entirely and immediately rather than gradually phased out. This demonstrates a critical strategic principle: marginalized communities themselves often articulate the most radical demands and drive movements forward through their intellectual and organizational contributions. Figures like Frederick Douglass, an escaped enslaved person, became a towering intellectual force, publishing the newspaper North Star and establishing himself as a leading abolitionist theorist. Sojourner Truth, Isabella Baumfree, and Henry Highland Garnet similarly emerged as eloquent voices challenging slavery’s foundations and calling for dramatic action.[2][3][1]

Political Violence and Armed Resistance: Beyond the Nonviolence Narrative

A critical but often obscured dimension of Black abolitionism was its embrace of armed self-defense and political violence as legitimate tools of liberation. The dominant historical narrative emphasizes nonviolent resistance, but Black abolitionists understood that slavery itself was inherently violent and that violence would be necessary to destroy it. In 1851, the Christiana Resistance witnessed armed Black abolitionists and two Quakers successfully defending fugitive slaves against enslavers and slave catchers. When Edward Gorsuch, the white enslaver, arrived with a posse to recapture fugitives, Eliza Parker—a Black abolitionist woman—sounded an alarm, mobilizing eighty armed Black men and women with guns and pitchforks who arrived within minutes. After shots were fired, Gorsuch was killed, with historical accounts noting that “the women put an end to him,” emphasizing how Black women were as likely as men to employ force in self-defense.[4]

This violent resistance was not aberrant but systematic. By the 1850s, following the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Black communities formed vigilance committees and militias across Northern towns, transforming daily life in places like Christiana into “flashpoints over the Fugitive Slave Act”. A shift from “prayers and petitions to politics and pistols” occurred as abolitionism evolved into a more militant enterprise. This strategic expansion of tactics—combining legal petitioning, cultural assertion, economic pressure, and armed self-defense—provides a crucial lesson for contemporary movements: the most effective resistance often operates across multiple registers simultaneously, refusing false dichotomies between “violence” and “nonviolence” while maintaining strategic clarity about when force becomes justified in defense of fundamental rights.[4]

Reconstruction and the Seizure of Political Power: Legal Mobilization and Black Self-Determination

Freedmen’s Conventions, Voter Registration, and the Construction of Parallel Institutions

The Reconstruction period (1865-1877) represents a dramatic, though tragically brief, moment when freed Black people seized political power and began constructing institutions aligned with their interests. Rather than passively accepting emancipation, Freedmen’s conventions held in 1865 and 1866 across the South demonstrated autonomous Black political organizing. These conventions protested the Black Codes—discriminatory laws enacted by former Confederate states to restrict the civil rights of newly freed people—and petitioned Congress for full voting rights. The conventions articulated a vision of democracy based on racial equality, with delegates arguing, “Give us the suffrage and you may rely upon us to secure justice for ourselves”.[5][6]

When the Reconstruction Acts of 1867-1868 enfranchised Black men, over 1,500 African Americans were elected to public office in the South. Some of these leaders were formerly enslaved people who had escaped North, gained education, and returned to build institutions serving their communities. Federal troops and Freedmen’s Bureau offices provided crucial protection for Black political participation and voter registration, enabling Blacks to achieve higher rates of educational access, occupational mobility, and farm ownership in counties with intensive federal presence. These gains persisted into the early twentieth century where Reconstruction was most rigorously enforced, suggesting that state protection of marginalized political participation can produce measurable improvements in socioeconomic outcomes.[7][5]

However, this promising moment was violently reversed. White supremacist groups including the Ku Klux Klan, White League, and Red Shirts engaged in paramilitary terrorism to disrupt Reconstruction governments. By 1876, the Compromise of 1877 effectively ended federal protection, withdrawing troops and enabling the restoration of white political dominance through disenfranchisement laws, Jim Crow segregation, and systematic violence.[5]

Strategic Lesson: The Necessity of Institutional Enforcement

Reconstruction’s tragic reversal illuminates a critical insight: legal rights alone are insufficient without institutional structures and continuous mobilization to enforce them. The moment federal enforcement mechanisms weakened, whites deployed systematic disenfranchisement, literacy tests with racial “grandfather clauses,” and violence to reverse Black political gains. This underscores that in India’s context, Downtrodden (Dalit) political representation through reservation policies requires not merely legal guarantees but sustained institutional mechanisms, community mobilization, and state capacity to prevent backlash and enforce protections.[5]

The Civil Rights Movement: Nonviolent Mass Mobilization, Strategic Women’s Leadership, and Intersectional Organizing

Rosa Parks, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and Economic Resistance

The post-World War II civil rights movement revived and expanded the repertoires of Black resistance developed in earlier periods. The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956) demonstrated the power of coordinated economic resistance—a tactic rooted in earlier “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns of the Depression era. By refusing to purchase bus tickets, Black Montgomerians leveraged their economic power to demand access to dignity and equal treatment. The boycott succeeded in desegregating public transportation and validated the strategic principle that Black consumer power, when organized collectively and sustained over time, can force concessions from major institutions.[8][9]

Rosa Parks, the woman whose arrest sparked the boycott, was a carefully trained activist and member of the NAACP, though media narratives often portrayed her as a spontaneous symbol rather than a strategic organizer. This pattern of erasing women’s deliberate organizing recurs throughout civil rights historiography, with male leaders receiving disproportionate credit for victories achieved through collective labor.

Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Black Women’s Grassroots Leadership

Black women were the backbone of the Civil Rights Movement, yet remain systematically underrecognized in dominant narratives. Ella Baker, born in 1903, was the “mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” dedicating over five decades to social justice while rejecting the “great man” leadership model. Baker served as a field secretary for the NAACP in the late 1940s, traveling the South to charter new branches and build local organizations. She later became executive secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and, most notably, mentored and guided the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).[10][11]

Baker’s genius lay in her advocacy for “participatory democracy” and “leadership from the bottom up”—an approach that privileged grassroots organizing and rejected the charismatic, hierarchical leadership style that dominated 1960s activism. She believed that ordinary people possessed the capacity and right to lead their own liberation. Her mentees, including John Lewis, Diane Nash, and Kwame Ture, revered her as their “political mother,” and her organizational philosophy shaped SNCC’s approach to student activism, Freedom Rides, and voter registration campaigns.[12][11][10]

Fannie Lou Hamer exemplified grassroots leadership emerging from the material conditions of Black oppression. A Mississippi sharecropper and mother of six, Hamer became politicized through economic exploitation and personal violence—she was forcibly sterilized by a white doctor and beaten brutally by police while attempting to register to vote. Rather than remaining silent, Hamer traveled Mississippi organizing voter registration drives, founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), and delivered a televised testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention that exposed the brutality of Southern white supremacy to national audiences. Her speeches wove together spiritual hymns, biblical references, and searing political analysis, creating a powerful synthesis of faith, politics, and personal testimony that resonated across communities. Hamer’s work directly registered thousands of Black voters and, through the Freedom Farm Cooperative, provided material support and agricultural training to disenfranchised Black families.[13][10]

Dorothy Height, leading the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) for 40 years, ensured that Black women’s perspectives shaped every major civil rights initiative. Though less visible in photographs than male leaders, Height was instrumental in planning the March on Washington and consistently pushed the movement to integrate women’s rights with racial justice.[11][12]

These women’s contributions reveal that intersectional leadership—connecting struggles across race, gender, and class—was central to civil rights organizing from its inception, rather than being a later theoretical addition. Their emphasis on grassroots organizing, participatory democracy, and material support for base communities provides models for contemporary movements seeking to build power from below.

Strategic Litigation and Constitutional Victories

While mass mobilization was crucial, the movement also achieved constitutional victories through strategic litigation. Pauli Murray, a Black queer feminist lawyer and civil rights pioneer, developed legal arguments that became foundational to civil rights jurisprudence. Murray’s legal scholarship on the intersection of gender, race, and sexuality informed arguments in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared school segregation unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s decisions dismantling “separate but equal” doctrine, affirming voting rights, protecting freedom of expression, and recognizing fundamental rights to marriage across racial lines—including Loving v. Virginia (1967) on interracial marriage—created legal frameworks that constrained state-sanctioned discrimination, though their enforcement remained incomplete and contested. [14][12]

Black Cultural Assertion and the Black Arts Movement: Narrative Control and Aesthetic Resistance

Alongside political and legal mobilization, Black communities deployed cultural and artistic resistance as weapons against white supremacy and tools for building community consciousness. The Black Arts Movement (1965-1975) emerged symbolically the day after Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965, when poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) moved from New York’s Lower East Side to Harlem and established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre. The movement was, as poet Larry Neal wrote, “the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept,” emphasizing Black self-determination, the celebration of Black beauty and culture, and militant political engagement.[15][16][17]

Black Arts Movement poets and artists consciously deployed language and form as resistance. They drew on Black musical traditions—jazz, blues, gospel—and Black vernacular speech, deliberately rejecting the white literary establishment’s standards of “proper” language and aesthetics. Amiri Baraka’s plays and poetry employed violent imagery and fierce language to challenge white supremacy and call for liberation. Haki Madhubuti’s writings articulated the movement’s mission: “How do we become a whole people, and how do we begin to essentially tell our narrative, while at the same time move toward a level of success?”. Nina Simone’s “Young, Gifted and Black” became an anthem of self-affirmation, fusing classical training with blues and gospel to create a distinctive aesthetic that celebrated Black culture while politically challenging racism.[16][17][15]

The Black Arts Movement also established independent cultural institutions—theaters, publishing houses, magazines—creating economic and cultural spaces outside white institutional control. This institutional independence proved financially fragile, as mainstream theaters and publishers eventually co-opted select Black artists, leading to financial collapse of many grassroots outlets. Nevertheless, the movement demonstrated that narrative control and cultural self-representation are central to liberation struggles, not peripheral to “real politics.” By insisting on the right to tell their own stories in their own aesthetic forms, Black Arts activists rejected the narratives imposed by white supremacy.[17][15]

Digital Mobilization and Contemporary Black Activism: From #BlackLivesMatter to Economic Boycotts

Social Media, Hashtag Activism, and the Amplification of Police Violence

The killing of unarmed Black people by police has been endemic to American racism, yet historically received minimal media coverage or official accountability. Digital platforms revolutionized how Black communities document, amplify, and politically mobilize around police violence. In 2013, after George Zimmerman’s acquittal for killing Trayvon Martin, three Black women—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, and Opal Tometi—created the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, which became a rallying cry for movements against state violence.[18][19][20][21]

The hashtag spread explosively. From July 2013 through May 2018, #BlackLivesMatter was tweeted over 30 million times—averaging 17,002 times per day. By June 2020, following George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, the hashtag had been tweeted roughly 47.8 million times, with peak usage reaching nearly 500,000 tweets per day. This digital mobilization created networked publics that transcended geographic boundaries, enabling people globally to witness police brutality in real-time and participate in coordinated protests.[19][20][18]

Social media platforms, particularly Instagram, enabled visual documentation of state violence with unprecedented reach and speed. Multimodal analysis of Instagram posts addressing police brutality reveals that BLM and allied activists used hashtags like #SayHisName and #SayHerName to create networks of remembrance, documenting the systematic killing of Black people and demanding recognition of victims’ humanity. Visual affordances of platforms enabled emotional solidarity, with followers amplifying posts through likes, comments, and shares, creating alternative narratives to official police statements.[18]

Importantly, BLM’s leadership reflected intersectional commitments established by earlier movements. Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Alicia Garza, both Black queer women, ensured that the movement addressed police violence against Black LGBTQ+ people, Black women, Black immigrants, and other marginalized communities within the Black diaspora, preventing the movement from centering only heterosexual cisgender men. This intersectional grounding distinguished BLM from earlier movements that sometimes marginalized or excluded queer and trans activists.[21]

Youth-Led Digital Activism and the Globalization of Resistance

Generation Z has expanded the repertoires of digital activism beyond hashtags to encompass TikTok videos, Discord servers, Instagram infographics, and coordinated campaigns spanning multiple platforms. Young people use digital spaces not merely to document injustice but to develop civic identities, express political commitments, and organize offline action. A 2020 UK study found that 34% of 8-17-year-olds report the internet has inspired them to take action about a cause, while 43% say it makes them feel their voices matter.[22][23]

Youth-led movements have leveraged digital tools to achieve global coordination. The School Strike for Climate movement (March 2019) mobilized 1.4 million youth across countries, with local protests documented on Twitter and then replicated elsewhere through “glocal” networking—simultaneously local and global. Similarly, Gen Z activists have organized around racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and climate justice, using social media to connect isolated individuals into movements while maintaining the flexibility of decentralized organization.[23][22]

This digital activism has produced measurable results. The hashtag #MeToo, initiated by African American sexual assault survivor Tarana Burke in 2006, brought visibility to sexual violence against marginalized women, particularly Black women and women of color who face disproportionate sexual violence. Digital campaigns against corporate backlash on diversity initiatives—including the 2024-2025 boycotts of Target and other companies retreating from DEI commitments—leveraged social media to coordinate consumer pressure, resulting in CEO resignations and measurable corporate losses.[9][21][8]

Mutual Aid Networks and Community Care: Economic Resistance Beyond Markets

Alongside digital mobilization, contemporary Black liberation movements have revived and innovated mutual aid practices as alternatives to market provision and state neglect. The Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program served 20,000 meals weekly to Black children in 1969, not merely providing charity but creating spaces for community analysis, movement building, and liberation. Black Panthers understood nutrition and health as political questions inseparable from antiracism and economic justice.[24][25]

Contemporary mutual aid networks continue this tradition. During the COVID-19 pandemic, radical mutual aid organizations organized collective shopping for immunocompromised community members, established food pantries, and created neighborhood “pods” for mutual support. Queer mutual aid organizations like Pansy Collective mobilized within 48 hours of Hurricane Helen in North Carolina to provide direct assistance when government disaster response proved inadequate. These networks operate on principles of solidarity rather than charity—rejecting the paternalism of hierarchical aid distribution and instead fostering reciprocal relationships where all participants both give and receive.[25][24]

Community bail funds, bystander intervention trainings, and cop-watch programs represent mutual aid merged with political organizing, serving immediate survival needs while building community power and consciousness. These practices recognize that sustainable liberation requires ongoing material support and collective care, not merely political victories disconnected from daily survival.[24]

Economic Resistance: From Montgomery to Contemporary Boycotts

Black communities have consistently deployed economic resistance as a lever for change. The “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns during the Great Depression in cities like Chicago, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh pressured businesses to hire Black workers, yielding hundreds or thousands of jobs. In Durham, North Carolina, the 1968-1969 “Black Christmas” boycott of downtown businesses and Northgate Shopping Center, organized by the Black Solidarity Committee for Community Improvement, achieved negotiations on six joint committees addressing welfare, housing, employment, and Black representation. The boycott succeeded despite lacking the mass media coverage of more publicized campaigns, demonstrating that disciplined, organized economic resistance achieves results even without mainstream attention.[26][8][9]

Contemporary boycotts have reignited these tactics. When Target retreated from DEI commitments in 2025, Pastor Jamal Bryant’s organized boycott, amplified through digital channels, produced immediate measurable consequences: Target’s sales plummeted and income dropped 21%, leading to the CEO’s resignation within months. In contrast, Costco, which maintained DEI commitments, saw increased customer loyalty and rising sales, demonstrating consumer alignment with progressive corporate positions.[8][9]

These successes reveal the power of sustained, focused economic action. However, boycotts also present risks for Black businesses. Black-owned brands stocked in targeted retailers face sales declines when consumers boycott major chains, highlighting tensions between macro-level pressure and micro-level consequences for Black entrepreneurs. Strategists emphasize that effective boycotts require complementary “buy-cotts” directing support to Black-owned businesses and alternatives, ensuring that economic pressure produces not merely corporate losses but wealth accumulation and economic sovereignty for Black communities.[9][8]

Intersectionality, Queer Leadership, and Gender Justice: From Black Feminist Theory to Practice

The theoretical and practical frameworks of intersectionality—understanding how race, gender, sexuality, class, and other identities interact to produce distinct experiences of oppression—emerged from Black feminist organizing and intellectualism. Pauli Murray’s theorization of how gender, race, and sexuality intersect provided conceptual foundations. In the 1960s-1970s, while mainstream (white) feminism ignored Black women’s distinctive experiences, Black women organized the Black Feminist Movement, centered on intersectional analysis and committed to opposing racism, sexism, and homophobia simultaneously.[21]

This intersectional commitment distinguished Black liberation movements from many other social movements. While second-wave feminism often excluded Black women and queer women, the Black Lives Matter movement—founded by queer and trans Black women—has consistently centered the most marginalized members of Black communities. BLM platforms address anti-trans violence, police violence against Black immigrants, sexual violence against Black women, and interconnected systems of oppression rather than treating race as an isolated category.[22][21]

Black queer and trans activists have played pivotal leadership roles despite facing exclusion even within progressive Black movements. Queer and trans Black women articulate how caste-like systems within Black communities—including homophobia and transphobia—reinforce white supremacist hierarchies. This analysis reveals that liberation requires dismantling all systems of hierarchy, not merely racial oppression in isolation. [27][28][21]

Contemporary Black queer feminist discourse emphasizes joy and pleasure as dimensions of resistance, not merely responses to oppression. Scholars argue that Black queer communities create joy “created anew”—not dependent on material circumstances but emerging from collective self-determination and cultural production. This framework moves beyond deficit-focused narratives of trauma and resilience to recognize Black queer creativity as inherently liberatory.[28]

Strategic Parallels and Lessons: From American Black Resistance to India’s Marginalized Communities

Having traced Black American resistance across multiple centuries and registers, we now turn to exploring how Downtrodden (Dalit), Adivasi, and Bahujan communities in India can draw strategic inspiration from these experiences while adapting them to India’s specific contexts of caste oppression, communal violence, and differential state capacity.

Downtrodden (Dalit) Movements: Legal Mobilization, Political Representation, and the Fight for Constitutional Rights

The Indian Constitution, adopted in 1950, included groundbreaking provisions theoretically protecting Scheduled Castes (Downtrodden) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) from discrimination and caste-based violence. Article 17 abolished untouchability; Articles 14 and 15 guaranteed equality before law and prohibited caste-based discrimination; Article 16(4) enabled reservation policies for SCs/STs in government employment and education. These constitutional provisions represented a massive intellectual and political victory, particularly since B.R. Ambedkar, himself a Downtrodden (Dalit), served as Chair of the Constitution Drafting Committee.[29][30][31]

However, as the Supreme Court observed in 2021, atrocities against SCs and STs “continue to be a reality” despite these constitutional safeguards. Police officials refuse to register complaints, victims fear retaliation from dominant castes, and perpetrators evade conviction due to inadequate investigation and prosecution. This gap between legal rights and lived reality mirrors the situation in post-Reconstruction America, where constitutional amendments abolishing slavery and guaranteeing equal protection were systematically circumvented through Jim Crow laws, violence, and institutional neglect.[30]

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, represents a crucial legal instrument created in response to widespread caste violence. Enacted to address the inadequacy of earlier protections, the SC/ST Act creates specific criminal offenses for caste-based violence and establishes special courts for prosecution. Yet enforcement remains weak, with victims facing barriers at every stage—from initial complaint registration through trial. This pattern reveals that legal victories require sustained grassroots mobilization, media attention, and institutional accountability mechanisms to prevent the laws from becoming paper tigers.[30]

Ambedkar, Buddhist Conversion, and Religious Alternatives to Brahminical Structures

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar recognized that Hinduism’s theological foundations embedded caste hierarchy and that Downtrodden (Dalit) liberation required religious transformation, not merely legal reform. In 1956, Ambedkar led the conversion of over 500,000 Downtrodden (Dalit) to Buddhism—a dramatic assertion of collective self-determination and rejection of Hindu caste structures. This Buddhist conversion movement represented a strategic pivot away from integrationist hopes that constitutional democracy would dissolve caste hierarchy, instead constructing autonomous religious and cultural spaces where Downtrodden (Dalit) could practice dignity free from Brahminical domination.[32][33][34]

Ambedkar’s approach parallels how Black Muslims in America used Islam as an alternative to white Christian theology that had historically justified slavery and segregation. Both recognized that marginalized communities cannot rely on oppressors’ religious frameworks for liberation but must construct autonomous spiritual and philosophical systems aligned with their interests.[33]

The Dalit Panthers: Militant Resistance and the Radicalization of Downtrodden (Dalit) Youth

Just as the Black Panther Party in America represented a militant turn from civil rights nonviolence, the Dalit Panthers (founded 1972) represented a radical departure from integrationist Downtrodden (Dalit) politics. Founded by poets and young intellectuals including J.V. Pawar and Namdeo Dhasal, the Panthers adopted militant language and confrontational tactics to challenge caste atrocities.[35][36][37]

The Panthers emerged amid growing Downtrodden (Dalit) youth consciousness and specific incidents of state violence. In 1972, two Dalit women were forced to walk naked by dominant-caste villagers—incidents that crystallized Downtrodden (Dalit) outrage and motivated radical organizing. The Panthers adopted the slogan “Black Independence Day” to oppose the 25th Independence Day celebrations, arguing that independence from British rule had not liberated Dalits from caste slavery. This strategic language drew parallels between colonial and caste oppression, prefiguring later articulations of caste as a form of internal colonialism.[36][37][35]

The Panthers’ manifestos defined Downtrodden (Dalit) broadly to encompass “Scheduled Castes and Tribes, neo-Buddhists, the working-people, the landless and poor peasants, women, and all those being exploited politically, economically, and in the name of religion”. This expansive definition attempted to build solidarity across marginalized groups while maintaining analytical focus on caste and class oppression. The movement used radical poetry, theatrical performances, and direct action to bring visibility to caste violence while attacking both the dominant-caste perpetrators and complicit Downtrodden (Dalit) political leaders.[37][36]

Like the Black Panthers, the Dalit Panthers faced police repression, arrests, torture, and efforts to suppress their publications. Despite their brief organizational lifespan (roughly the 1970s-1980s), their impact on Downtrodden (Dalit) consciousness, literature, and organizing remains profound.[36][37]

Downtrodden (Dalit) Literature: Testimony, Counter-Narrative, and Consciousness-Raising

Downtrodden (Dalit) literature serves as a powerful vehicle for consciousness-raising, documentation, and counter-narrative production—analogous to Black Arts Movement cultural resistance. Downtrodden (Dalit) writers, emerging from the late nineteenth century but flourishing in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, create autobiographies, poetry, fiction, and testimonies that articulate Dalit experiences and assert Dalit humanity against centuries of dehumanization. [38][39][40]

Writers like Omprakash Valmiki, Bama Faustina, and Meena Kandasamy transform personal trauma into collective resistance through literary innovation, deploying folk idioms alongside contemporary techniques to reach diverse audiences. Their work documents not merely individual suffering but systemic caste violence, educational exclusion, land dispossession, and sexual violence against Downtrodden (Dalit) women. By writing in English, regional languages, and vernacular forms, Downtrodden (Dalit) writers reach educated audiences while remaining rooted in community languages and oral traditions.[38]

Downtrodden (Dalit) literature’s role in reshaping educational curricula, catalyzing national discourse, and empowering new generations of activists parallels how Black literature, music, and cultural production have continuously disrupted white supremacist narratives and enabled Black cultural survival. Both recognize that cultural production is political work essential to liberation struggles, not supplementary to “real” organizing.[15][16][17]

Digital Activism and the Downtrodden (Dalit) Camera: Contemporary Resistance Through Visual Documentation

In a contemporary parallel to Black Lives Matter’s use of social media to document police violence, Dalit Camera—a YouTube channel founded by Bathran Ravichandran—documents caste atrocities, Dalit activism, and counter-narratives to mainstream media’s erasure of caste. Established after 20 students attacked Ravichandran on his university campus, Dalit Camera operates as “a historical documentation of realities in India through the eyes of the untouchable”.[41][42][43]

Dalit Camera produces documentary-style videos, interviews, protest coverage, and analysis addressing everyday caste violence, institutional discrimination, sexual violence against Dalit women, and Dalit resistance movements. Their videos documenting anti-caste activist Rohith Vemula’s suicide—an institutional murder triggered by caste-based scholarship suspension and harassment by Hindu nationalist students—mobilized Dalit activists nationally and produced testimonies in Telugu celebrating his life and demanding justice. By making content in regional languages with Dalit perspectives, Dalit Camera reaches audiences excluded from mainstream English-language or upper-caste-dominated media.[42][43][41]

Hashtag activism on Twitter and other platforms has enabled rapid mobilization around caste atrocities. Hashtags like #DalitLivesMatter, #JusticeForRohithVemula, and #HathrasJustice trend during crises, keeping caste violence in national conversation and forcing mainstream media engagement. However, like Black digital activism, Downtrodden (Dalit) digital movements face challenges: content removal, algorithmic suppression, harassment of activists, and limited offline translation of online visibility into material political victories.[43]

Downtrodden (Dalit) Women and Intersectional Resistance: Gender, Caste, and Collective Liberation

Downtrodden (Dalit) women face compounded discrimination from both upper-caste domination and patriarchy within Downtrodden (Dalit) and broader Indian society. Scholars emphasize that Downtrodden (Dalit) women’s oppression is not merely the sum of caste and gender oppression but a distinct, embodied intersection producing unique experiences of violence, labor exploitation, and exclusion.[44][45][46]

Downtrodden (Dalit) women have been forced into manual scavenging, devadasi (sexual slavery to temples), and agricultural wage labor under conditions of brutal exploitation. Their bodies have been sites of systematic violence by upper-caste men and, increasingly, the state through forced sterilization and police brutality. Yet Dalit women have also pioneered distinctive forms of resistance. Organizations including the National Federation of Dalit Women (NFDW) and All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch (AIDMAM) have brought Dalit women’s issues to national and international forums, demanding education, land rights, legal literacy, and dignity.[45]

Downtrodden (Dalit) feminism provides crucial corrective to both mainstream feminism (which often ignores caste) and Downtrodden (Dalit) movements (which often marginalize women). Downtrodden (Dalit) feminist scholars like Sharmila Rege advocate a “standpoint feminist” approach recognizing Downtrodden (Dalit) women’s unique epistemic position and authority over their own experiences. Rather than accepting male-centered Downtrodden (Dalit) politics or upper-caste-centered feminism, Dalit women articulate independent demands centered on their own liberation.[46][44][45]

This intersectional approach parallels how Black women have insisted on centered leadership addressing racism and sexism simultaneously, rejecting movements that treat these as separate struggles. Both Downtrodden (Dalit) and Black women activists understand that liberation requires transforming all systems of hierarchy, not merely centering one axis of oppression.[11][21]

Adivasi Resistance, Land Rights, and Constitutional Self-Determination

While Downtrodden (Dalit) movements have centered caste as their primary axis of analysis, Adivasi (Indigenous) movements emphasize land rights, forest access, and collective self-determination against both caste and colonial capitalist encroachment. The Forest Rights Act (FRA) and Panchayats Extension to Scheduled Areas Act (PESA) theoretically protect Adivasi land and forest rights and establish Gram Sabhas (village councils) as decision-making bodies with autonomy in Scheduled Areas.[47][48][49]

However, these rights remain violated systematically. Over 54,000 hectares of Abujhmad forest are being acquired for an Indian Army training range, expected to displace over 10,000 Adivasis. Over 450 people have been killed since January 2024 in Bastar, Chhattisgarh—primarily Adivasis allegedly killed by police and paramilitary forces under the guise of anti-Naxalite operations. The violence accompanies expanding mining activities and military presence, revealing how Adivasi dispossession proceeds through simultaneous legal appropriation, militarization, and extra-judicial killing.[47]

Adivasi movements have deployed innovative forms of resistance including Pathalgadi—erecting boundary stones with constitutional provisions to assert territorial sovereignty and demand recognition of their rights. As one elder explained, “With Pathalgadi we know that we are special people and have specific protections under the Constitution”. This assertion of constitutional rights while simultaneously asserting territorial sovereignty represents a distinctive Adivasi politics refusing both assimilationism and marginalization.[48][49]

Movements like Moolvasi Bachao Manch (Tribal Protection Forum) have organized resistance to land acquisition and militarization, only to face state repression including arrest and organizational banning. This reveals structural parallels to how Black and Downtrodden (Dalit) activism face state violence and criminalization—a pattern across marginalized communities whose demands for justice threaten existing power structures.[47]

Periyar and the Self-Respect Movement: Rationalism, Women’s Rights, and Anti-Brahminism in South India

Periyar (E.V. Ramasamy), a key figure in Tamil Nadu’s caste resistance, developed a distinctive ideological approach emphasizing rationalism, women’s liberation, and Dravidian identity as alternatives to Brahminical domination. Periyar organized the Self-Respect Movement beginning in the 1920s, campaigning against untouchability, caste inequality, child marriage, and women’s subordination.[50][51][52]

Unlike Ambedkar’s emphasis on Buddhism and legal constitutionalism, Periyar deployed rationalist ideology and cultural assertion of Dravidian identity to challenge Brahminism. He argued that Vedas and Brahminical texts were not divine truth but human productions perpetuating caste hierarchy, and he famously declared his intention to burn these texts to demonstrate his rejection of their authority. This radical epistemological challenge—questioning the sacred texts undergirding caste oppression—parallels how Black intellectuals challenged Christian theology’s theological justifications for racism.[51][52][50]

Periyar’s self-respect ideology emphasized personal dignity, rational critique, and collective pride. He advocated reservations and affirmative action decades before Indian Constitution, believing historical injustices necessitated compensatory discrimination. His influence shaped Tamil Nadu politics, eventually leading to the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and transformation of Tamil Nadu into a state with comparatively stronger anti-Brahminical politics and greater assertion of non-Brahmin interests.[52][50][51]

From Inspiration to Strategy: Building Coalition Power in India’s Marginalized Communities

Coalition-Building Across Caste, Religion, Gender, and Class Lines

Effective social movements require coalitions bringing together diverse constituencies around shared demands while respecting distinctive identities and concerns. Research on coalition formation identifies critical factors: strong social ties and “bridge builders” with connections across groups; shared ideology and culture; conducive organizational structures; institutional environment enabling mobilization; and available resources.[53][54]

In the Indian context, coalitions must bridge Downtrodden (Dalit), Adivasi, Bahujan, and religious minority communities facing systematic oppression, while navigating tensions between their specific struggles. For instance, Downtrodden (Dalit) movements have sometimes marginalized Adivasi specificity, and Hindu nationalist politics have driven wedges between Hindu-majority Downtrodden (Dalit) communities and Muslim minorities facing communal violence. Effective coalitions must articulate shared analysis of oppressive systems while creating space for autonomous organizing and cultural specificity.[48][45][46]

Downtrodden (Dalit) feminist frameworks provide models for coalition-building across oppressed communities, as they insist on addressing multiple intersecting systems of oppression—caste, gender, class, religion—rather than treating any single axis as primary. When Downtrodden (Dalit) women organize around land rights, economic justice, and freedom from sexual violence, they necessarily create space for Adivasi women’s struggles and Muslim women’s experiences of communal violence.[44][45][46]

Narrative Control and Media Production: Creating Counter-Publics

Marginalized communities cannot rely on mainstream media to represent their struggles authentically. Instead, they must create autonomous media platforms producing counter-narratives and developing alternative public spheres. Downtrodden (Dalit) Camera’s success demonstrates how low-cost digital tools enable marginalized communities to document, analyze, and circulate their own representations.[41][42][43]

Strategic media production requires:

Investment in independent digital platforms (YouTube channels, podcasts, newsletters, social media accounts) enabling marginalized communities to control representation without filters of dominant-caste or upper-class gatekeepers. Regional language and vernacular production reaching audiences excluded from English-language or high-literacy media. Visual, textual, and audio formats accommodating diverse literacy levels and cultural preferences. Hashtag campaigns and trending strategies amplifying visibility of caste atrocities and generating pressure on mainstream media. Documentary and testimonial formats centering survivors and activists as knowledge producers rather than mere interview subjects.[42][43][41]

Indian marginalized communities can learn from Black media production that centers Black stories, aesthetics, and analysis rather than seeking white validation. This requires accepting that some platforms and audiences may not engage with counter-narratives initially—the goal is building alternative publics autonomous from dominant institutions, not convincing oppressors.[17][15]

Legal Mobilization and Institutional Accountability

While law cannot alone achieve liberation, strategic legal mobilization can constrain state violence, document atrocities officially, and create space for political organizing. The SC/ST Atrocities Act, reservation policies, land rights legislation, and constitutional provisions protecting marginalized communities provide legal resources that must be aggressively deployed.[31][55][30]

Strategic legal approaches include:

Public interest litigation (PIL) in higher courts documenting systemic atrocities and demanding governmental action. Complaint registration campaigns overwhelming police with demands to register cases and prosecute perpetrators, creating administrative pressure. Victim support and legal aid networks enabling survivors to navigate courts and pursuing cases through extended timeframes. International advocacy bringing cases to United Nations forums and international human rights bodies, creating pressure through global attention when domestic institutions fail. Media-court coordination ensuring court proceedings receive public attention, preventing quiet dismissals.[45][31][43][30][41]

Importantly, legal strategies must complement rather than substitute for political organizing and grassroots power-building. Laws are enforced only when communities mobilize to demand implementation, as Reconstruction’s reversal and civil rights victories’ partial implementation have demonstrated.

Economic Resistance: Boycotts, Alternative Markets, and Material Autonomy

Marginalized communities possess collective economic power that can constrain oppressive institutions and build autonomous economic spaces. Boycott strategies rooted in Black consumer activism can be adapted to Indian contexts:[8][24][9]

Organized consumer boycotts targeting corporations complicit in caste discrimination or Adivasi dispossession, requiring sustained coordination and clarity about demands. Buy-cotts supporting Downtrodden (Dalit)-owned, Adivasi-led, and marginalized-community businesses, creating wealth accumulation and economic sovereignty. Cooperative structures enabling collective ownership and equitable resource distribution—paralleling the Black Panthers’ community institutions and contemporary mutual aid networks. Alternative markets and direct producer-consumer relationships bypassing exploitative middlemen and building economic relationships rooted in solidarity rather than profit maximization.[25][24][9][8]

India’s existing cooperative structures, including women’s self-help groups and agricultural cooperatives, provide frameworks for scaling economic resistance. Digital platforms enable coordination across geographic distances, enabling marginalized communities to identify, support, and scale alternatives to exploitative mainstream markets.

Digital Mobilization and Social Media Strategy

Digital platforms provide unprecedented tools for marginalized communities to document injustice, organize mobilization, and build transnational solidarities. However, digital activism requires strategic sophistication to avoid co-optation, algorithmic suppression, and performative activism disconnected from material organizing.[43][18][22][41][42]

Effective digital strategies include:

Hashtag campaigns with clear political demands—not merely awareness-raising but calls to action. Visual storytelling combining documentary video, photography, infographics, and testimony to create emotional resonance alongside factual documentation. Coordinated posting strategies maximizing reach and algorithmic visibility through timing, cross-platform amplification, and engagement metrics. Offline-online integration ensuring digital mobilization translates into protests, direct action, community organizing, and institutional pressure. Language diversity producing content in regional languages and vernacular forms rather than defaulting to English. Community accountability preventing platform dynamics from privileging certain voices over others and maintaining connections to grassroots constituencies.[20][19][18][22][41][42][43]

Intersectional Leadership and Gender Justice

Marginalized communities cannot achieve liberation while reproducing patriarchy, homophobia, transphobia, and ableism internally. Intersectional leadership models—centered on women, queer people, trans people, disabled people, and other multiply-marginalized community members—produce stronger, more transformative movements.[27][28][46][21][44][45]

This requires:

Centering women’s leadership and paying women organizers, particularly Downtrodden (Dalit) women and Adivasi women whose analysis illuminates interconnected oppressions. Creating safe space for LGBTQ+ activists in movements often hostile to gender and sexual minorities, learning from Black LGBTQ+ organizing that has consistently advanced liberation movements. Prioritizing accessibility for disabled people through physical access, digital accessibility, mental health support, and pace-setting that doesn’t center able-bodied norms. Building accountability mechanisms addressing sexual violence, harassment, and patriarchy within movements rather than reproducing oppressive patterns while fighting external oppression.[10][11][21][27][44][45]

Downtrodden (Dalit) and Adivasi women have articulated these intersectional demands persistently; mainstreaming their analysis requires shifting power and resources toward their leadership.

International Solidarity and Transnational Coalition-Building

Marginalized communities globally face structurally similar oppression rooted in colonialism, racial capitalism, patriarchy, and religious hierarchies. Building transnational solidarities enables knowledge-sharing, material support, and amplification of struggles that might otherwise remain isolated and locally contained.[56][54][53][25]

Concrete strategies include:

Documented solidarity exchanges where activists from different contexts learn from each other’s organizing, adapted to their specific conditions. Shared analysis and theorization developing frameworks explaining how oppressive systems interconnect globally—understanding caste not merely as Indian phenomenon but as comparable to racial hierarchies globally. Material support networks channeling resources toward most vulnerable communities, complementing domestic funding. Joint statements and coordinated advocacy at international forums including UN bodies and regional human rights mechanisms. Decentralized coordination respecting autonomous decision-making while enabling coordinated pressure on shared targets.[54][56][53][18][24][45][25]

Black Lives Matter’s solidarity with Palestinian resistance—articulated through shared analysis of colonialism and racial capitalism—provides a model for how movements can build internationalism while respecting contexts’ specificities and centering locally-led organizing.[56][25]

Policy Reform: From Individual Rights to Structural Transformation

Policy reform isolated from grassroots power-building produces hollow victories as demonstrated by post-Reconstruction disenfranchisement and contemporary backlash against civil rights protections. Nevertheless, strategic policy demands anchored in mass movements can expand rights protections and constrain oppressive state violence.[57][55][5]

Criminal Justice and Security Sector Reform

Police and militarized security forces perpetuate violence against marginalized communities worldwide. Policies addressing this require simultaneous investment in community-based safety alternatives and accountability mechanisms for officers committing atrocities. Specific policy demands include:[55][57][30]

Special Fast-Track Courts with trained judges prosecuting atrocities against marginalized communities, ensuring justice rather than acquittal rates approaching 90% as currently occurs. Mandatory arrest and prosecution protocols for caste atrocities, overriding police discretion to ignore complaints. Community policing with community accountability, replacing military-style policing with officers embedded in communities and subject to community oversight. Demilitarization of Scheduled Areas and Downtrodden (Dalit) neighborhoods, replacing paramilitary occupation with community-controlled security structures. Reparations for victims including compensation, psychological support, and institutional reform ensuring non-recurrence.[57][55][30][47]

Education and Cultural Production

Marginalized communities cannot achieve liberation while educational systems and cultural institutions remain controlled by dominant groups and teach dominant narratives. Policy demands must include:

Affirmative action in faculty and administration, ensuring marginalized communities control educational institutions affecting their communities. Curriculum reform incorporating Downtrodden (Dalit) literature, Adivasi history, caste science, and perspectives from marginalized communities as central rather than supplementary. Protection for marginalized student activists facing violent suppression for demanding social justice—ensuring campuses become sites of liberation rather than reproduction of oppression. Public funding for independent media and cultural institutions run by marginalized communities, creating platforms autonomous from market pressures and state control. Language policies ensuring regional and minority languages receive equal status and resources as dominant languages.[38][44][45][41][42][43][47]

Economic and Land Rights

Structural economic transformation requires redistributing land and productive resources toward marginalized communities, not merely individual rights protections:

Comprehensive land reform redistributing government wasteland and agricultural land to landless Downtrodden (Dalit) and Adivasi communities, implementing demands Ambedkar articulated. Implementation of Forest Rights Act protecting Adivasi land and forest access against corporate extraction and military appropriation. Living wages and employment guarantees ensuring marginalized workers earn sufficient income to meet basic needs without state welfare dependence. Elimination of manual scavenging and hazardous occupational categories historically forced on Downtrodden (Dalit), with dignified alternative livelihoods. Asset redistribution and wealth transfer to communities historically robbed through slavery, colonialism, and caste oppression.[33][55][48][56][30][57][47]

Representation and Political Power

Marginalized communities require genuine political power to shape decisions affecting their lives, not merely consultation or tokenism:

Strengthened reservation policies expanding proportional representation of SCs/STs/OBCs in elected bodies, bureaucracy, judiciary, and security forces—with enforcement against evasion. Meaningful devolution of power to Gram Sabhas and community bodies in Scheduled Areas, respecting Adivasi self-determination. Decentralization and participatory democracy enabling grassroots communities to control decisions about their neighborhoods, schools, and resources rather than distant bureaucrats. Campaign finance reform reducing wealthy donors’ political power and enabling marginalized communities to fund candidates independently.[49][46][55][10][11][48][21][44][45][57]

Conclusion: Toward Transformative Liberation

The centuries-long resistance of Black Americans to white supremacy—from slavery-era abolitionist organizing through contemporary digital activism—demonstrates that oppressed communities possess remarkable capacity for sustained, innovative struggle across changing historical conditions. Black resistance has evolved through armed self-defense, legal mobilization, mass nonviolent action, cultural production, economic power, and digital mobilization—never settling into a single tactic but rather expanding the repertoire of liberation while maintaining focus on fundamental demands: dignity, self-determination, economic justice, and collective liberation.

Simultaneously, India’s marginalized communities have waged parallel struggles against caste, religious oppression, and economic domination, developing distinctive approaches rooted in their own histories, philosophies, and organizational traditions. Downtrodden (Dalit) movements draw on Ambedkarite thought emphasizing constitutional democracy, Buddhist conversion, and political representation. Adivasi movements center territorial sovereignty and land rights. Periyarist and Dravidian movements deploy rationalism and regional identity. Together, these movements articulate a vision of India as a land where all communities live in dignity, free from caste hierarchy, communal violence, and economic exploitation.

The strategic parallels are profound: both contexts reveal that liberation requires simultaneously advancing political representation and military/police accountability; developing autonomous cultural institutions and media platforms; building grassroots power through collective organizing and community solidarity; deploying legal and institutional mechanisms while maintaining skepticism toward state benevolence; emphasizing intersectional leadership centered on women and LGBTQ+ people; and connecting struggles globally while respecting local autonomy and cultural specificity.

Yet transformation ultimately requires not merely remaking institutions within existing systems but fundamentally reconstructing social relations around principles of collective liberation, mutual aid, and dignity. This demands policy reform alongside cultural revolution—changing laws while simultaneously changing consciousness, expanding what communities understand as possible. It requires sustained organizing amid repeated setbacks and co-optation, building institutions that survive repression and maintain vision across generations.

The Black Freedom struggle continues into an uncertain future, facing renewed backlash against civil rights protections, militarized policing targeting marginalized communities, and systemic racism embedded in every institution. Similarly, Downtrodden (Dalit) and Adivasi communities face intensifying state violence, communal attacks, and capitalist displacement, even as they sustain movements demanding justice. Yet the historical record demonstrates that marginalized communities transform themselves through struggle, develop new forms of consciousness and organization, and create possibilities seemingly impossible beforehand.

The work ahead requires Indian marginalized communities to learn from Black resistance—not to imitate but to adapt lessons to their distinctive contexts. This means building coalitions across caste, religion, gender, and class while centering those most oppressed; producing counter-narratives and controlling media representation; deploying law strategically while maintaining skepticism toward state institutions; sustaining grassroots organizing across decades of incremental progress and dramatic reverses; leading with women and queer activists whose analysis illuminates interconnected oppression; and connecting struggles internationally while remaining accountable to local constituencies demanding transformation.

The vision animating both Black and marginalized Indian communities is one of collective liberation—not merely individual freedom from oppression but collective reconstruction of social relations founded on equality, democracy, and mutual aid. This vision emerged from centuries of struggle, from ordinary people refusing oppression and collectively imagining alternatives. Actualizing it requires sustained commitment, strategic sophistication, willingness to learn and adapt, courage to face repression, and faith in collective capacity for transformation. The historical record suggests this is possible. The future depends on whether marginalized communities can sustain the movements this moment demands.

- http://fas-history.rutgers.edu/bay/TAAI_FreeBlacksAndAbolition.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abolitionism_in_the_United_States

- https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/african/resistance-and-abolition/

- https://www.aaihs.org/the-role-of-violence-in-the-abolitionist-movement/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstruction_era

- https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/reconstruction/voting-rights

- https://www.economics.harvard.edu/resource/freedomroaddeadendpdf

- https://caro.news/the-power-of-the-black-dollar-a-century-of-economic-boycotts/

- https://www.communityvoiceks.com/2025/03/03/black-economic-boycott-success-goes-on/

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/women-in-the-african-american-civil-rights-movement-an-historic-context.htm

- https://www.albert.io/blog/black-women-civil-rights-leaders-ap-african-american-studies-review/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/list-of-key-figures-in-the-American-civil-rights-movement

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fannie_Lou_Hamer

- https://civics.supremecourthistory.org/eras/incorporating-rights/

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/collections/148936/an-introduction-to-the-black-arts-movement

- https://fiveable.me/african-american-literature-since-1900/unit-5/amiri-baraka-black-arts-movement/study-guide/3A5lRACY9b1SmCJS

- https://www.albert.io/blog/the-black-arts-movement-ap-african-american-studies-review/

- https://thesis.eur.nl/pub/65003/Korhonen_Sara.pdf

- https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2387/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Lives_Matter

- https://now.org/blog/the-original-activists-black-feminism-and-the-black-feminist-movement/

- https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220803-gen-z-how-young-people-are-changing-activism

- https://globalfundforchildren.org/story/modern-day-youth-activism-youth-engagement-in-the-digital-age/

- https://afsc.org/news/how-create-mutual-aid-network

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9347405/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_Blackout

- https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=ugrad_theses

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11848048/

- https://dennana.in/2025/03/06/dalit-movement-in-india/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheduled_Caste_and_Scheduled_Tribe_(Prevention_of_Atrocities)_Act,_1989

- https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT25A4866.pdf

- https://vajiramandravi.com/current-affairs/dalit-movements-in-india/

- https://ras.org.in/index.php?Article=b_r_ambedkar_on_caste_and_land_relations_in_india

- https://www.journalofpoliticalscience.com/uploads/archives/4-2-18-450.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalit_Panthers

- https://journals.library.brandeis.edu/index.php/caste/article/download/693/1955

- https://www.forwardpress.in/2019/04/short-but-impactful-life-of-dalit-panthers/

- https://www.academia.edu/120627972/Role_of_Dalit_Literature_in_Social_Change_in_India

- https://czasopisma.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters/article/download/6953/6529/18411

- https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jdms/papers/Vol13-issue4/Version-5/U013459197.pdf

- https://asapconnect.in/post/380/singlestories/documenting-dalit-resistance

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-25502849

- https://www.ijraset.com/best-journal/caste-gender-and-media-stereotypes-a-study-of-representation-and-resistance

- https://clpr.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Intersectionality-A-Report-on-Discrimination-based-on-Caste-with-the-intersections-of-Sex-Gender-Identity-and-Disability-in-Karnataka-Andhra-Pradesh-Tamil-Nadu-and-Kerala.pdf

- https://theacademic.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/140.pdf

- https://lhsscollective.in/the-dalit-movement-within-the-feminist-movement/

- https://icmagazine.org/india-crackdowns-on-adivasi-communities-spark-global-outcry/

- https://www.forwardpress.in/2019/11/an-adivasi-rebellion-to-uphold-the-constitution/

- https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/dissolving-go-3-threat-to-jal-jangal-jameen/

- https://hubsociology.com/e-v-ramasamy-periyar-his-movements-for/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periyar

- https://countercurrents.org/dalit-periyar280603.htm

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8108406/

- https://sites.ucmerced.edu/files/nvandyke/files/van_dyke_and_amos_-_social_movement_coalitions.pdf

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001203

- https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/post/mutual-aid-and-a-pluralistic-account-of-solidarity

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10897090/

- https://hmh.org/about/25-human-rights-advocates-organizations/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_rights_movement

- https://www.lwv.org/blog/women-civil-rights-movement

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-025-04535-2

- https://pacificlegal.org/plf-supreme-court-track-record/

- https://www.actec.org/resource-center/video/landmark-civil-rights-cases-decided-by-the-supreme-court/

- https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/11830

- https://theconversation.com/consumer-resistance-is-rising-in-the-age-of-trump-history-shows-how-boycotts-can-be-effective-251448

- https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15338/1/scheduled_castes_and_the_scheduled_tribes.pdf

- https://hpa.haryanapolice.gov.in/pdfs/study material/Handbook.pdf

- https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/soc4.12858

- https://www.migpolgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/FINAL-VERSION-Policy-brief-Oct-2024.pdf

- https://www.humanitiesjournal.net/archives/2025/vol7issue2/PartE/7-2-56-505.pdf