Casteist Journalism and Its Implications on Society: An Analysis of Media Bias and Social Justice in India

Journalism, often regarded as the fourth pillar of democracy, carries the profound responsibility of shaping public discourse, challenging power structures, and giving voice to the marginalized. However, when journalism itself becomes a vehicle for perpetuating caste-based discrimination and prejudice, it undermines its fundamental purpose and inflicts deep wounds on society’s fabric. Casteist journalism—the practice of reporting, framing, and disseminating news through the lens of caste hierarchies and prejudices—represents one of the most insidious challenges facing media ethics and social justice today.

The phenomenon of casteist journalism extends far beyond overt discrimination. It manifests in subtle editorial choices, representational gaps, linguistic codes, and institutional structures that collectively reinforce centuries-old hierarchies. From the underrepresentation of marginalized castes in newsrooms to the sensationalization of caste-based violence, from the perpetuation of stereotypes to the erasure of anti-caste voices, casteist journalism operates through multiple mechanisms that demand critical examination.

Understanding Casteist Journalism

Casteist journalism represents a complex manifestation of structural discrimination within India’s media ecosystem, where news production, editorial decisions, and narrative construction are influenced by caste-based hierarchies and prejudices. This phenomenon extends beyond mere underrepresentation to encompass systematic exclusion, stereotypical portrayal, and the perpetuation of dominant-caste perspectives as universal truths. [1][2][3][4]

The concept encompasses multiple dimensions of bias, including editorial gatekeeping by predominantly dominant-caste decision-makers, selective news coverage that downplays caste-based atrocities, framing effects that present marginalized communities through deficit models, and source selection that privileges dominant-caste voices in discussions about caste-related issues. These practices collectively create what scholars term a “casteist media ecosystem” that reinforces existing social hierarchies rather than challenging them. [3][4][5][6][1]

Mechanisms of Casteist Bias in Media

The manifestation of casteist journalism operates through several interconnected mechanisms that scholars have identified through extensive research. Language and terminology choices often reflect caste prejudices, with media outlets frequently using coded language that reinforces stereotypes or employs euphemisms that dilute the severity of caste-based violence. Story selection and prioritization demonstrate clear patterns where issues affecting dominant-caste communities receive disproportionate coverage compared to systemic problems faced by downtrodden (Dalits & Adivasis). [1][3][4][7]

Visual representation in both print and electronic media consistently marginalizes downtrodden (Dalit and Adivasi) communities, either through complete absence or through stereotypical portrayals that reinforce existing prejudices. Expert sourcing patterns reveal a pronounced bias toward dominant-caste academics, activists, and commentators even when discussing issues directly affecting marginalized communities. These mechanisms work synergistically to create a media environment where dominant-caste perspectives are normalized while marginalized voices are systematically excluded or misrepresented. [2][4][6][8][9][1]

Representation Gap: Population vs Media Leadership in Indian Journalism

Statistical Evidence of Systemic Exclusion

The most compelling evidence of casteist journalism emerges from comprehensive quantitative studies that document the stark underrepresentation of marginalized communities in India’s media landscape. The landmark 2019 Oxfam-Newslaundry study, which analyzed over 65,000 articles across English and Hindi publications, revealed shocking disparities in representation. [9][10]

Dominant castes, comprising merely 20% of India’s population, occupy an overwhelming 88% of newsroom leadership positions across major media outlets. This dominance extends to content creation, with dominant-caste journalists producing 95% of all articles in English newspapers and 90% in Hindi publications. In stark contrast, downtrodden (Dalits), who constitute 16.6% of the population, hold zero representation in newsroom leadership positions and contribute to less than 5% of English newspaper articles. [10][11][9]

The study found that three out of every four anchors of flagship debate shows belong to dominant castes, with no representation from downtrodden (Dalit & Adivasi), or OBC communities in prime-time discussions. Even more troubling, over 70% of flagship debate show panellists are drawn from dominant castes, creating echo chambers that exclude diverse perspectives on critical social issues. This data starkly illustrates how India’s media functions as an exclusive dominant-caste domain that systematically marginalizes the voices of over 80% of the population. [11][12][9][10]

Historical Context and Evolution

The roots of casteist journalism in India trace back to the colonial period and the early days of the independence movement, when media ownership and editorial control were concentrated among educated dominant-caste elites. The 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the emergence of newspapers like The Hindu and The Indian Mirror, which often portrayed downtrodden (Dalits) and other marginalized communities through deficit lenses, reinforcing colonial and Brahmanical stereotypes. [1][6][13]

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s prescient recognition of media bias led to the establishment of Mooknayak (Leader of the Voiceless) in 1920, marking the first systematic attempt to create alternative media platforms for marginalized communities. Ambedkar astutely observed that mainstream media served specific caste interests while remaining indifferent to the concerns of others, writing in the first edition of Mooknayak: “If we throw even a cursory glance over the newspapers that are published in the Bombay presidency, we will find that many among these papers are only concerned about protecting the interest of some castes”. [6][13][14]

The post-independence period saw the institutionalization of these biases through formal media structures that continued to privilege dominant-caste perspectives while marginalizing downtrodden (Dalit and Adivasi) voices. The 1920s through 1940s represented a golden period of downtrodden (Dalit) journalism, with publications like Bahishkrut Bharat and various regional publications challenging dominant narratives. However, the consolidation of mainstream media under corporate control gradually squeezed out these alternative voices, leading to the current crisis of representation. [12][13][6]

Contemporary Manifestations and Case Studies

Modern casteist journalism manifests through subtle yet pervasive practices that shape public understanding of caste-related issues. The Rohith Vemula case exemplifies how mainstream media initially downplayed the role of caste discrimination in the young scholar’s suicide, with several outlets suggesting factors other than institutional casteism were responsible. This tendency to deflect attention from structural casteism represents a consistent pattern in media coverage of caste-related incidents. [1][7][15]

Coverage of caste-based violence frequently exhibits problematic framing that focuses on law and order aspects while ignoring the underlying structural causes of such incidents. The recent case of a nine-year-old downtrodden (Dalit) boy beaten to death by his teacher in Rajasthan’s Jalore district illustrates this pattern, with mainstream outlets primarily debating whether the incident was “caste-driven” rather than examining the systemic factors that enable such violence. [8][16][17][1]

Linguistic bias represents another significant manifestation, with media outlets often using euphemistic language to describe caste atrocities while employing harsh terminology for crimes involving dominant-caste victims. Visual representation patterns consistently marginalize Downtrodden (Dalit & Adivasi) communities, either through complete absence from advertisements and programming or through stereotypical portrayals that reinforce existing prejudices. [2][7][18][8]

Television programming, particularly in entertainment media, perpetuates harmful stereotypes by depicting downtrodden-caste characters as uneducated, criminal, or servile while maintaining dominant-caste dominance in positive roles. These representations have far-reaching implications for public perception and social attitudes toward marginalized communities. [1][2][8]

Impact on Marginalized Communities and Social Cohesion

The implications of casteist journalism extend far beyond media representation, profoundly affecting the lived experiences of marginalized communities and broader social cohesion. Psychological impact on Downtrodden (Dalit and Adivasi) communities includes internalized oppression, reduced self-esteem, and limited aspirational horizons when positive role models and success stories from their communities remain invisible in mainstream media. [4][11]

Political participation suffers when marginalized communities lack adequate representation in media discourse, limiting their ability to influence public policy debates and electoral outcomes. The absence of diverse voices in media discussions about education, healthcare, employment, and social policy ensures that the specific needs and perspectives of marginalized communities remain unaddressed in policy formulation. [10][12][19]

Social violence and discrimination are perpetuated when media coverage fails to adequately contextualize caste-based atrocities within broader patterns of systematic oppression. When media outlets treat isolated incidents of caste violence as aberrations rather than symptoms of structural discrimination, they contribute to public apathy and policy inaction. [1][7][8][15][17]

Economic implications emerge when discriminatory media practices limit access to employment opportunities for qualified Downtrodden (Dalit and Adivasi) professionals in media industries. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where lack of representation in media workforces reinforces exclusion from media narratives and public discourse. [11][12][20][4][10]

Educational impact manifests when young people from marginalized communities lack positive media representation, affecting their career aspirations and self-perception. The absence of successful Downtrodden (Dalit and Adivasi) role models in media contributes to reduced educational motivation and limited professional aspirations among these communities. [6][12][14][11]

A woman wearing a pink saree seated indoors, symbolizing the presence and activism of Downtrodden (Dalit) journalists in Indian media.

Alternative Media Movements and Digital Resistance

The emergence of alternative media platforms represents a significant response to mainstream media’s casteist bias, with downtrodden (Dalit, Adivasi) communities leveraging digital technologies to create independent narrative spaces. Contemporary alternative media platforms such as Round Table India, Dalit Camera, The Mooknayak, Velivada, and Justice News have created robust ecosystems for marginalized voices. [21][22][23]

Digital activism through platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube has enabled marginalized communities to document atrocities, challenge stereotypes, and build solidarity networks across geographical boundaries. The Dalit Camera YouTube channel, for instance, functions as an archive of downtrodden (Dalit) experiences while providing a platform for community organizing and consciousness-raising. [4][22][23][24]

Khabar Lahariya, the all-women media collective from rural Uttar Pradesh, exemplifies how marginalized communities are creating innovative media models that challenge both caste and gender hierarchies. Their transition from print to digital media demonstrates the transformative potential of technology in democratizing media production and distribution. [11]

However, these alternative platforms face significant challenges including limited financial resources, restricted reach compared to mainstream media, technical barriers, and coordinated harassment campaigns by dominant-caste groups seeking to silence marginalized voices. The digital divide also limits access for many Downtrodden (Dalit and Adivasi), particularly in rural areas, constraining the reach and impact of alternative media initiatives. [10][12][23]

Ethical Implications and Professional Standards

The persistence of casteist journalism raises fundamental questions about professional ethics and the role of media in democratic societies. Press Council of India guidelines explicitly prohibit caste-based discrimination in reporting, stating that “recognition of the caste or class of a person should be avoided, particularly when in the context it conveys a sense or attributes a conduct or practice derogatory to that caste”. [25][26][27]

Violation of journalistic principles occurs when media outlets fail to provide accurate, fair, and comprehensive coverage of caste-related issues. The principle of objectivity is compromised when newsrooms lack diverse perspectives and when editorial decisions are influenced by caste prejudices rather than news values. [26][28][25]

Professional training and education in journalism programs rarely address caste sensitivity or the specific challenges faced by marginalized communities. This educational gap perpetuates cycles of exclusion by failing to prepare future journalists to recognize and address their own biases. [28][29]

Accountability mechanisms remain weak, with press councils and media watchdogs lacking the authority or inclination to enforce meaningful sanctions against casteist reporting practices. The self-regulatory nature of media ethics enforcement allows discriminatory practices to continue with minimal consequences. [27][25][26]

International journalism standards emphasize diversity, inclusion, and representation as core professional values, highlighting how Indian media practices fall short of global best practices. The failure to implement these standards not only violates professional ethics but also undermines media credibility and public trust. [29][25][28]

Regulatory Framework and Legal Dimensions

India’s legal and regulatory framework provides multiple avenues for addressing casteist journalism, though enforcement remains problematic. Constitutional provisions under Articles 14, 15, 16, and 17 prohibit caste-based discrimination and guarantee equality before law, creating a legal foundation for challenging discriminatory media practices. [25][30]

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act includes provisions that could theoretically apply to media content that promotes hatred or discrimination against these communities. However, practical application of these provisions to media content remains limited due to enforcement challenges and definitional ambiguities. [31][25]

Press Council of India regulations establish ethical guidelines for caste-sensitive reporting, but the council’s quasi-judicial powers are limited to moral censure rather than punitive action. The voluntary nature of compliance with these guidelines reduces their effectiveness in preventing discriminatory practices. [26][27][25]

Recent legal developments, including the Supreme Court’s judgment in Sukanya Shantha v. Union of India regarding caste-based discrimination in prisons, demonstrate growing judicial recognition of the need to address systemic casteism in public institutions. This precedent could potentially extend to media institutions, creating new legal avenues for challenging discriminatory practices. [30][32]

International human rights law, including the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), provides additional frameworks for addressing caste-based discrimination in media. India’s commitments under these international instruments create obligations to prevent and remedy discriminatory practices in all sectors, including media. [25]

Solutions and Recommendations

Addressing casteist journalism requires comprehensive, multi-stakeholder interventions that target structural, institutional, and cultural dimensions of the problem. Diversity and inclusion initiatives must go beyond tokenistic hiring to implement meaningful affirmative action policies in media organizations. This includes establishing minimum representation targets for Downtrodden (Dalit, Adivasi), and OBC communities in newsrooms, editorial boards, and management positions. [9][11][12][14]

Educational reform in journalism programs should incorporate mandatory courses on caste sensitivity, social justice reporting, and intersectional analysis. Media literacy programs for the general public can help audiences critically evaluate news content and recognize caste biases in reporting. [18][28][29]

Funding mechanisms for alternative media platforms need strengthening through public-private partnerships, civil society support, and innovative financing models that reduce dependence on advertising revenue from caste-privileged businesses. Technology platforms can implement policies to prevent the harassment and suppression of marginalized voices while promoting diverse content. [12][14][19][21][18]

Regulatory strengthening should include enhanced powers for press councils to investigate and sanction discriminatory practices, along with clearer guidelines on caste-sensitive reporting. Industry self-regulation through professional associations can establish peer review mechanisms and professional development programs focused on inclusive journalism practices. [25][26][27][28][29]

Community-based monitoring initiatives can document instances of casteist journalism and advocate for improved coverage of marginalized communities. Collaboration between mainstream and alternative media can create pathways for incorporating diverse perspectives into mainstream narratives while building capacity in alternative media platforms. [7][14][17][21][22][18]

Global Context and Comparative Perspectives

The challenge of casteist journalism in India resonates with broader global patterns of media discrimination based on race, ethnicity, and social class. International research demonstrates how marginalized communities worldwide face similar patterns of exclusion, misrepresentation, and stereotyping in mainstream media. [33]

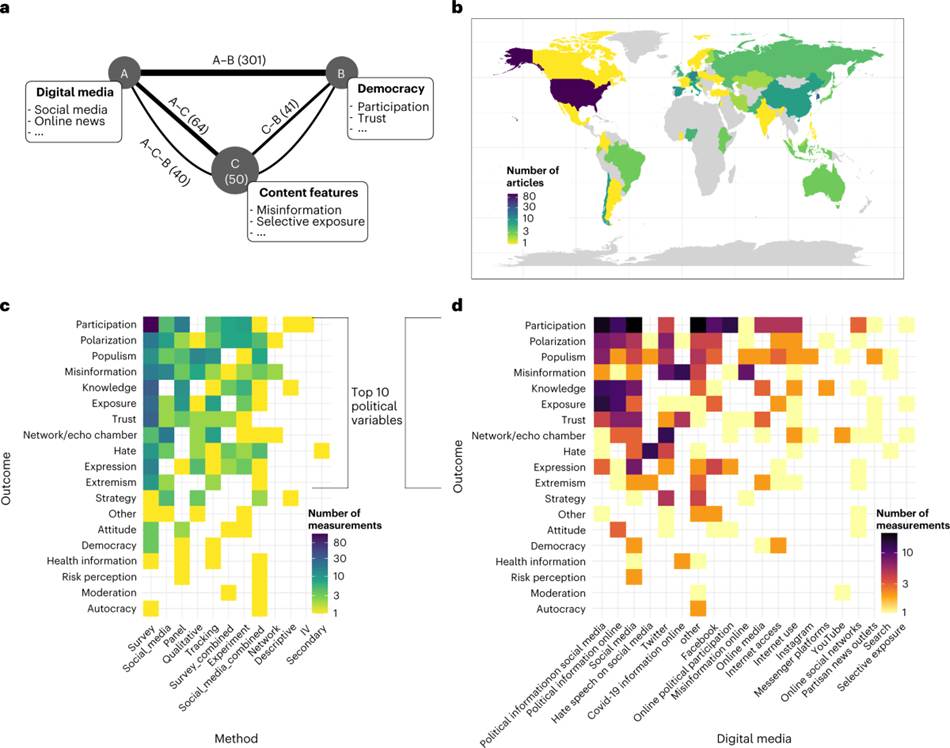

Global overview of research on digital media’s impacts on democracy, content features, and political outcomes across countries and methods.

Studies from the United States, United Kingdom, and other democratic societies reveal parallel structural biases that privilege dominant groups while marginalizing minorities.

Digital media’s dual impact mirrors global trends where technology simultaneously democratizes content creation while replicating existing power structures. The rise of social media platforms has created new opportunities for marginalized voices globally, but these platforms also enable coordinated harassment campaigns and the spread of discriminatory content. [18][19]

Best practices from other countries include affirmative action policies in media organizations, public funding for diverse media content, and regulatory frameworks that actively promote inclusion rather than merely prohibiting discrimination. Media development programs in various countries demonstrate how targeted interventions can increase diversity and improve coverage of marginalized communities. [28][29]

International advocacy efforts by human rights organizations increasingly recognize media representation as a critical component of broader equality and justice initiatives. The United Nations and other international bodies have developed frameworks for assessing media diversity and promoting inclusive journalism practices that could inform Indian policy interventions. [25]

Technological Transformation and Future Prospects

The rapid digitization of India’s media landscape presents both opportunities and challenges for addressing casteist journalism. Artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-making in content distribution can either amplify existing biases or be programmed to promote diverse perspectives. Data analytics can help track representation patterns and measure progress toward inclusion goals. [9][10][19]

Emerging platforms such as podcasts, streaming services, and independent digital channels are creating new spaces for marginalized voices, though access remains limited by economic and technological barriers. Mobile technology penetration in rural areas offers opportunities to reach previously excluded audiences with alternative narratives. [11][21][23][24]

Generational change among media consumers, particularly younger audiences who are more receptive to diverse perspectives and social justice content, creates market incentives for inclusive journalism. Crowdfunding and subscription models enable independent media outlets to reduce dependence on traditional advertising and corporate sponsorship. [14][21][29]

Virtual and augmented reality technologies offer new possibilities for immersive storytelling that can challenge stereotypes and build empathy across caste lines. Blockchain and decentralized technologies could potentially create censorship-resistant platforms for marginalized voices. [19][23]

Conclusion

Casteist journalism represents one of the most significant challenges to India’s democratic media landscape, perpetuating structural inequalities that undermine social justice and inclusive development. The systematic exclusion of marginalized voices from mainstream media not only violates professional journalistic ethics but also impedes India’s constitutional commitment to equality and social justice.

The evidence presented demonstrates that current patterns of media ownership, editorial control, and narrative construction serve to reinforce caste hierarchies rather than challenge them. This situation demands urgent, comprehensive intervention that addresses structural, institutional, and cultural dimensions of discrimination within India’s media ecosystem.

The emergence of alternative media platforms and digital resistance movements offers hope for transformative change, but these initiatives require sustained support and systemic reforms to achieve their full potential. The path forward requires collaborative efforts among media organizations, civil society, government institutions, and marginalized communities themselves to create a truly inclusive and representative media landscape.

Only through such comprehensive transformation can India’s media fulfill its democratic mandate to serve as a platform for all voices and perspectives, contributing to the creation of a more just and equitable society. The implications extend far beyond media representation to encompass broader questions of democracy, citizenship, and social cohesion in contemporary India.

The time for cosmetic changes and token gestures has passed; what is needed now is fundamental structural reform that recognizes media diversity and inclusion not as charitable obligations but as essential prerequisites for a functioning democracy. The future of Indian journalism—and indeed Indian democracy—depends on the media’s ability to transcend caste-based exclusions and embrace its role as a truly public institution serving all citizens regardless of their social origins.

- https://journal.hmjournals.com/index.php/JMCC/article/download/1708/2003/3324

- https://www.ijraset.com/research-paper/caste-gender-and-media-stereotypes

- http://onlineregistration.bgco.ca/news/subtle-caste-bias-in-media

- https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Oxfam NewsLaundry Report_For Media use.pdf

- https://www.apc.org/en/news/proposal-caste-ing-out-media-exploring-role-media-plays-ushering-caste-sensitive-society

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/5038699.pdf?abstractid=5038699&mirid=1

- https://www.polecom.org/index.php/polecom/article/download/162/406/770

- https://www.hindusforhumanrights.org/news/caste-system-in-india-and-its-representation-in-popular-cinema

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5038699

- https://www.fairplanet.org/story/in-their-own-words-dalit-journalists-challenge-media-bias/

- https://idsn.org/report-dalits-and-adivasis-missing-from-mainstream-indian-news-media-dominant-castes-dominate-leadership-positions/

- https://feminisminindia.com/2020/04/03/rise-fall-dalit-journalism-india/

- https://www.statecraft.co.in/article/dalit-journalists-indian-mainstream-media-a-manifestation-of-caste-and-class-privilege

- https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/04/04/980097004/indias-lowest-caste-has-its-own-news-outlet-and-shes-in-charge

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/meet-the-dalits-who-are-using-online-platforms-to-tell-stories-of-their-community/story-nkg4lHQ1DL44DbCBiJ7CrN.html

- https://sprf.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/SPRF-2021_Dalit-Media_Final.pdf

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/how-one-woman-defies-caste-discrimination-in-india

- https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/dalits-and-social-media/

- https://m.thewire.in/article/caste/full-text-why-a-journalist-filed-a-petition-against-caste-based-practices-in-indias-prisons

- https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol19-issue2/Version-5/R01925125129.pdf

- https://www.dw.com/en/india-dalit-journalists-give-a-voice-to-the-marginalized/a-66067288

- https://blog-iacl-aidc.org/2024-posts/2024/12/5/the-case-of-caste-based-discrimination-in-indian-prisons-a-new-constitutional-right-to-overcome-prejudice

- https://jmi.ac.in/upload/advertisement/ccmg_PrePhD_2023september18.pdf

- https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/06/world/asia/india-caste-discrimination-dalit-journalist-mooknayak.html

- https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/journalists-from-indias-lowered-castes-are-making-their-stories-known

- https://feminisminindia.com/2023/01/30/dalit-women-journalists-resistance-against-the-caste-bias-discrimination/

- http://archives.christuniversity.in/disk0/00/00/71/89/01/1424054_Tessy_Jacob_28_Nov_PM.pdf

- https://www.theswaddle.com/by-stifling-marginalized-voices-social-media-mimics-real-life-casteism

- https://www.tezu.ernet.in/tu_codl/slm/Open/MAMCD/2/MMC-201-BLOCK-II.pdf

- https://desikaanoon.in/media-coverage-on-sensitive-issues-an-analysis-on-law-and-ethics-of-media-reporting/

- https://www.ijirct.org/download.php?a_pid=2406074

- https://thekashmirhorizon.com/2024/03/19/role-of-ethics-and-law-in-indian-journalism/

- https://www.presscouncil.nic.in/WriteReadData/PDF/Norms2010.pdf

- http://www.mahratta.org/CurrIssue/2019_March/March19_4.pdf

- https://aaft.edu.in/blog/what-are-the-ethics-of-journalism-in-india