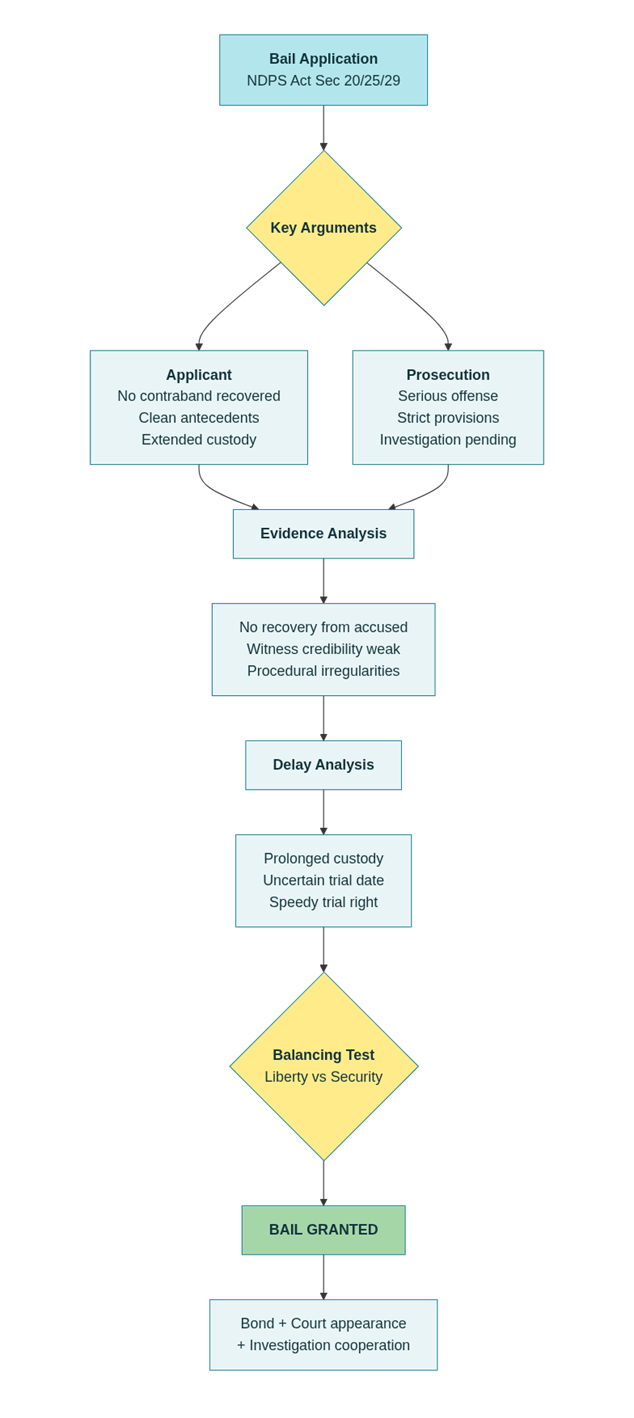

Landmark Delhi High Court Judgment: Vivek Kumar v. State (NCT of Delhi) – A Comprehensive Analysis on NDPS Bail and the Right to Speedy Trial

The Delhi High Court’s recent decision in Bail Application No. 1552/2025 (Vivek Kumar v. State of NCT of Delhi), rendered on December 12, 2025, by Justice Amit Mahajan, represents a significant development in the jurisprudence governing bail in narcotic drug cases. The judgment demonstrates a nuanced approach to balancing the state’s compelling interest in combating drug trafficking with the fundamental constitutional rights of accused persons, particularly their right to a speedy trial and liberty under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The case provides crucial insights into how courts are addressing evidentiary deficiencies, the weight of procedural irregularities, and the impact of prolonged pre-trial detention on bail decisions in NDPS cases governed by the stringent provisions of Section 37 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985.

The Factual Matrix and Criminal Charges

The case originated from FIR No. 192/2023, registered on March 25, 2023, at Police Station Subzi Mandi in Delhi. According to the prosecution’s version, acting on secret information received on March 24, 2023, a police raiding party apprehended Vivek Kumar (the applicant) and co-accused Sonu Kumar from an auto-rickshaw driven by co-accused Mehboob Ali in the Subzi Mandi area. The charges invoked against Vivek Kumar encompassed Sections 20, 25, and 29 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, which deal with the cultivation, transportation, and possession of narcotic drugs with the intention to commit an offense.[1]

The alleged recoveries in the case were substantial, constituting what is termed a “commercial quantity” under NDPS jurisprudence. The initial recovery consisted of 20 kilograms of ganja from the footrest of the passenger seat of the auto-rickshaw in which the accused were traveling. Significantly, following the disclosure statements allegedly made by Vivek Kumar and his co-accused during interrogation, the prosecution claimed to have recovered an additional 290 kilograms of ganja from two different locations—specifically 125 kilograms and 165 kilograms respectively. This aggregate quantity of 310 kilograms placed the case squarely within the commercial quantity threshold under NDPS provisions, thereby triggering the stringent bail conditions prescribed under Section 37 of the NDPS Act.[1]

A critical fact in the narrative is that Vivek Kumar was arrested on March 25, 2023, and had remained in custody for substantially more than two and a half years at the time of the bail application, with charges still not framed despite the considerable passage of time. This delay in the trial process became a pivotal consideration in the court’s eventual decision.[1]

The Legal Framework: Section 37 of the NDPS Act and Its Stringent Conditions

To understand the significance of the High Court’s decision in Vivek Kumar’s case, one must first comprehend the extraordinary restrictive nature of Section 37 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985. Unlike general bail jurisprudence under the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), which operates on the principle that “bail is the rule and jail is the exception,” Section 37 reverses this presumption in NDPS cases, particularly those involving commercial quantities. Under this provision, bail becomes the exception and pre-trial detention becomes the rule for accused persons charged with serious narcotics offenses.[2][3]

Section 37 stipulates that bail in NDPS cases can be granted only if the court is satisfied regarding two crucial twin conditions. First, the court must have reasonable grounds to believe that the accused is not guilty of the offense charged—a formidable burden that shifts the onus of proof substantially toward the defense, contrary to the fundamental principle of criminal law that presumes innocence. Second, the court must be satisfied that the accused is unlikely to commit any offense if released on bail. These conditions represent a marked departure from conventional bail jurisprudence and exist precisely because the legislature recognized that drug trafficking poses an extraordinary threat to societal wellbeing and public health.[4][5][3][2]

The rationale underlying Section 37’s stringency is well-articulated in legal literature and case law: drug trafficking “not only eats into the vitals of the society” but the proceeds of illicit drug trafficking are frequently channeled into other criminal activities, including terrorism. The legislature thus considered it essential to impose stringent pre-trial detention conditions to prevent accused persons from continuing their nefarious activities or absconding from the judicial process.[6]

However, this strict statutory framework has increasingly come into tension with constitutional protections guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which secures the fundamental right to life and personal liberty. The Supreme Court and various High Courts have grappled with reconciling this tension, leading to the development of important jurisprudential principles that now temper the absolute application of Section 37’s restrictions.[7][8][9]

Legal Reasoning Structure in Vivek Kumar NDPS Bail Case

The Applicant’s Arguments: False Implication and Procedural Irregularities

The counsel for Vivek Kumar articulated multiple grounds challenging the prosecution’s case and advocating for bail, each grounded in constitutional and legal principles. The applicant’s primary contention was that he had been falsely implicated in the present case and was innocent of the charges leveled against him. This assertion formed the foundation upon which subsequent arguments were built.[1]

The applicant emphasized a critical procedural lacuna: despite the fact that the initial recovery of 20 kilograms of ganja was made from an auto-rickshaw in a busy public place, no public witness (independent witness) had been joined by the prosecution in the search and seizure process. This omission is particularly significant because in narcotics cases, the involvement of independent witnesses serves as a crucial safeguard against police misconduct, planting of evidence, and fabrication. The requirement for independent witnesses is not merely procedural formality but a protective mechanism rooted in criminal jurisprudence and repeatedly endorsed by the Supreme Court.[7][9][1]

Furthermore, the applicant’s counsel pointed out the complete absence of any corroborative audio-visual documentation of the recovery process. In the modern era where digital technology is ubiquitous and readily accessible, the failure to photograph or videograph the recovery—particularly when it occurred in a public place where such documentation could have been undertaken—casts serious questions on the transparency and reliability of the seizure procedure. The applicant submitted that there was no CCTV footage, video recording, or photography to demonstrate that the recovery was actually made from the applicant.[1]

A related argument advanced by the defense pertained to the applicant’s status in relation to the alleged offense. Even accepting the prosecution’s case at its highest (meaning taking all the prosecution allegations as true), the applicant argued that he was merely a passenger in the auto-rickshaw and not the person actually in possession of or controlling the contraband. This distinction is legally and constitutionally significant because criminal liability demands a proximate connection between the individual and the criminal activity—mere presence at the scene without active participation may be insufficient for conviction.[1]

The applicant also highlighted his prolonged incarceration—approximately two and a half years—without charges being framed. This delay in the trial process became a powerful argument for bail on the grounds of fundamental fairness and the constitutional right to a speedy trial.[1]

The Prosecution’s Countervailing Arguments

The Additional Public Prosecutor for the State of NCT of Delhi presented arguments centered on the seriousness of the charges and statutory restrictions. The prosecution emphasized that the sheer magnitude of contraband recovered—the aggregate quantity of 310 kilograms of ganja—attracted the stringent provisions of Section 37 of the NDPS Act. In NDPS jurisprudence, the quantity of contraband recovered is itself a critical factor in determining both the severity of the offense and the applicability of the statutory bail restrictions.[1][4]

The prosecution further argued that the recoveries made from locations other than the initial auto-rickshaw seizure were the result of disclosure statements allegedly made by Vivek Kumar during interrogation. Under NDPS jurisprudence, such disclosure-based recoveries are considered significant evidence of the accused’s knowledge and involvement in the drug trafficking enterprise, as they demonstrate that the accused possessed specific information about the location of hidden contraband.[1]

Additionally, the State relied on Call Detail Records (CDR) connectivity between the applicant and other accused persons as circumstantial evidence linking the applicant to the alleged conspiracy. CDR connectivity establishes that the applicant had telephonic communication with co-accused persons, which the prosecution argued corroborated the conspiracy allegation.[1]

The prosecution also placed reliance on the fact that the bail application of co-accused Mehboob Ali had already been dismissed by the same court. This argument, however, carried limited logical force since each accused’s case must be evaluated on its individual merits, circumstances, and evidence.[1]

The Court’s Analysis: Section 37 Conditions and Procedural Safeguards

Justice Amit Mahajan’s analysis began with an articulation of well-established principles governing bail applications generally. The Court noted that when considering bail applications, courts must keep in mind multiple factors: whether there exists a prima facie case against the accused; the circumstances peculiar to the specific accused; the likelihood of offense recurrence; the nature and gravity of the accusations; the severity of potential punishment upon conviction; the danger of the accused absconding; and the reasonable apprehension of witness intimidation.[1]

The Court unequivocally acknowledged that to secure bail for an NDPS offense, the accused must fulfill the conditions stipulated in Section 37 of the NDPS Act. This recognition established that the court was not disregarding the statutory framework but rather interpreting and applying it within constitutional bounds.[1]

Significantly, the Court proceeded to examine the quality and reliability of the prosecution’s evidence with meticulous scrutiny. The judgment notes that although the recovery from the auto-rickshaw was effected in a busy public place on the basis of secret information, no public witnesses were joined by the prosecution and no photography or videography was conducted to corroborate the recovery. Similarly, despite having ample opportunity, the prosecution failed to associate public persons during the secondary recoveries allegedly effected based on disclosure statements.[1]

The Court then articulated a crucial principle that has become increasingly central to NDPS bail jurisprudence: while the absence of independent witnesses and audio-visual documentation would not be fatal to the prosecution’s case at trial, such procedural gaps can, in certain circumstances, cast a shadow over the credibility of the prosecution’s evidence. The Court noted that reliance on the testimony of official witnesses (police personnel) is permissible if established that these witnesses harbor no animosity toward the accused that would motivate false implication. However, the testimonies of official witnesses cannot be mechanically accepted merely because they are police officials; the absence of corroborating independent evidence raises legitimate questions about the reliability of the official narrative.[1]

The Court buttressed this reasoning by reference to the Delhi High Court’s earlier decision in Bantu v. State Govt of NCT of Delhi: 2024 DHC 5006. In that case, the Court had observed that while independent witness testimony is sufficient to secure conviction if it inspires confidence during trial, the lack of independent witnesses in certain cases can cast doubt upon the credibility of the prosecution’s case. Importantly, the Court in Bantu held that when the investigating agency has had sufficient time to prepare before a raid is conducted, the absence of public witnesses combined with the lack of photography and videography in the contemporary era—when such documentation is readily available—casts serious doubt on the credibility of the evidence.[7][1]

The applicability of this principle to Vivek Kumar’s case was evident. The police had received secret information in advance (on March 24, 2023) regarding the scheduled movement of accused persons with contraband, thereby allowing time for preparation of the raid. Yet despite this advance notice and the availability of technology, no public witnesses were secured and no audio-visual documentation was created. The prosecution offered a “mechanical explanation” that although some persons were asked to join the investigation, they left after citing their reasons—an explanation repeated identically for both the initial seizure and the subsequent disclosure-based recoveries. The Court found this mechanical repetition of the same explanation suspect, observing that the benefit of doubt regarding the lack of corroboration must be extended to the applicant at the bail stage, to be tested more rigorously during trial.[1]

Regarding the CDR connectivity argument, the Court held that in the absence of any supporting material linking the applicant to the contraband or recovery, CDR connectivity alone was insufficient to establish the applicant’s involvement. The mere fact of telephonic communication does not establish participation in a criminal conspiracy without additional corroborating evidence.[1]

Overcoming Section 37: The Doctrine of Delay in Trial

The most transformative aspect of the judgment pertains to the Court’s treatment of the applicant’s prolonged incarceration in relation to the stringent provisions of Section 37 of the NDPS Act. This dimension of the ruling reflects significant evolution in Supreme Court jurisprudence and represents a crucial check on unlimited pre-trial detention even in serious drug trafficking cases.

The applicant emphasized that he had remained in custody since March 25, 2023—a period extending beyond two and a half years—and charges had not yet been framed. The Court recognized this as a powerful factor militating in favor of bail. This recognition embodied an important legal principle: grant of bail on the grounds of undue delay in trial cannot be said to be fettered by the statutory embargo under Section 37 of the NDPS Act.[1]

The Court grounded this principle in landmark Supreme Court jurisprudence, particularly the decision in Mohd. Muslim v. State (NCT of Delhi): 2023 SCC OnLine SC 352. In that watershed case, the Supreme Court observed that laws imposing stringent conditions for bail may be necessary in public interest; yet if trials are not concluded in time, the injustice inflicted on the individual is immeasurable. The Supreme Court in Mohd. Muslim noted with profound concern that as of December 31, 2021, over 554,034 prisoners were lodged in jails against a total capacity of 425,069, with 122,852 being convicts and 427,165 being undertrials. This quantitative observation underscores the systemic problem of trial delay and undertrial incarceration in the Indian criminal justice system.[10][11][1]

The Supreme Court in Mohd. Muslim further described the phenomenon of “prisonisation” as articulated by the Kerala High Court in A Convict Prisoner v. State. Prisonisation is “a radical transformation” whereby the prisoner loses his identity, becomes known only by a number, loses personal possessions and personal relationships. The prisoner suffers psychological problems from the loss of freedom, status, possessions, dignity, and autonomy. The inmate culture of prison becomes dreadful, and the prisoner becomes hostile by ordinary standards, with self-perception fundamentally altered.[1]

The Supreme Court warned of a further danger: that incarcerated individuals, exposed to the prison culture where crime becomes “not only admirable but the more professional the crime, the more honour is paid to the criminal,” may themselves be drawn toward criminality. The Mohd. Muslim judgment also highlighted the particularly deleterious effects of incarceration on accused persons from the weakest economic strata, who face immediate loss of livelihood and, in many cases, scattering of families and alienation from society.[1]

Drawing upon this Supreme Court framework, Justice Mahajan emphasized that courts must be sensitive to these societal consequences and ensure that trials—especially in cases where special laws enact stringent provisions—are taken up and concluded speedily. The Court applied Section 436A of the CrPC, which mandates release on bail when an undertrial has served more than half the maximum sentence, observing that grant of bail on the ground of delay in trial cannot be fettered by Section 37 of the NDPS Act.[1]

The Court referenced additional Supreme Court authorities supporting this principle. In Man Mandal & Anr. v. The State of West Bengal: SLP(CRL.) No. 8656/2023, the Supreme Court had granted bail to a petitioner in an NDPS case on the ground that the accused had been incarcerated for almost two years and the trial was likely to take a considerable amount of time.[10][1]

In Rabi Prakash v. State of Odisha: 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1109, while granting bail to the petitioner, the Supreme Court held that the prolonged incarceration—more than three and a half years—must weigh heavily against the statutory embargo of Section 37(1)(b)(ii). The Supreme Court in that case reasoned that “the conditional liberty must override the statutory embargo created under Section 37(1)(b)(ii) of the NDPS Act.”[1]

Justice Mahajan synthesized this jurisprudence into a coherent principle: various courts have recognized that prolonged incarceration fundamentally undermines the right to life and liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution, and therefore conditional liberty must take precedence over statutory restrictions under Section 37 of the NDPS Act. This principle represents a constitutional check on legislative restrictions that, if applied without limitation, would result in indefinite pre-trial detention contrary to fundamental rights.[1]

Evidentiary Deficiencies and the Applicant’s Role

The Court’s examination of whether the evidence actually established Vivek Kumar’s culpability proved significant. The prosecution’s core allegations rested on the discovery of 20 kilograms of ganja in the auto-rickshaw in which the applicant was traveling. However, the Court noted that the applicant could arguably be characterized as merely a passenger in the vehicle rather than its owner or the person in actual possession and control of the contraband. Without evidence establishing that the applicant was in conscious possession of or exercised dominion and control over the drugs, establishing guilt under Section 20 of the NDPS Act—which penalizes “whoever cultivates, produces, manufactures, possesses, sells, purchases, transports, imports inter-State, exports, uses or abuses any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance”—would require careful evaluation of the evidence.[1]

The secondary recoveries, while voluminous in quantity, were entirely dependent on disclosure statements allegedly made by the accused during custodial interrogation. Indian criminal law, through the Evidence Act and constitutional protections, has long harbored suspicions regarding confessions made in police custody, recognizing the inherent coercive atmosphere and potential for abuse. The courts treat such disclosure-based evidence with caution, recognizing that it may be elicited through psychological or physical pressure. While disclosure-based recoveries are admissible in evidence if the disclosure itself is voluntary, the courts must carefully assess whether the disclosure and subsequent recovery actually establish the accused’s knowledge and involvement or merely reflect the accused’s attempts to cooperate under duress.[1]

The Requisite Personal Condition of the Applicant

Recognizing that the accused’s personal attributes and history constitute relevant considerations in bail jurisprudence, the Court noted that Vivek Kumar was stated to have clean antecedents—that is, no prior criminal convictions. This absence of a criminal history militated against the apprehension that he would commit offenses if granted bail, thereby partially satisfying the second condition under Section 37.[1]

The Bail Order and Its Conditions

Upon analysis, the Court determined that the applicant had made out a sufficient case for grant of regular bail. The judgment represents a sophisticated balancing of the competing interests: the state’s legitimate concern in preventing drug trafficking and securing the accused’s presence during trial, against the individual’s fundamental rights to liberty and a speedy trial.[1]

The Court accordingly directed that Vivek Kumar be released on bail on furnishing a personal bond for a sum of ₹25,000 with two sureties of the like amount, subject to the satisfaction of the learned Trial Court. This moderate bail amount reflects the Court’s confidence in the applicant’s likelihood of appearance and the absence of significant flight risk.[1]

The bail conditions imposed were carefully calibrated to address the prosecution’s legitimate concerns while preserving the accused’s liberty. These conditions included the following critical requirements:[1]

- The applicant shall not directly or indirectly make any inducement, threat, or promise to any person acquainted with the facts of the case or tamper with evidence in any manner whatsoever.[1]

- The applicant shall under no circumstance leave the boundaries of the country without permission of the learned Trial Court.[1]

- The applicant shall appear before the learned Trial Court as and when directed.[1]

- The applicant shall provide the address where he would reside after release and shall not change the address without informing the concerned Investigating Officer or Station House Officer.[1]

- Upon release, the applicant shall give his mobile number to the concerned Investigating Officer or Station House Officer and shall keep his mobile phone switched on at all times.[1]

The Court also preserved the prosecution’s right to seek cancellation of bail if any new FIR, diary entry, or complaint is lodged against the applicant, thereby maintaining governmental safeguards against the misuse of bail.[1]

Importantly, the Court clarified that observations made in the order were solely for the purpose of deciding the bail application and should not influence the outcome of the trial nor be taken as an expression of opinion on the merits of the case. This clarification exemplifies judicial wisdom in separating the bail determination (which must assess the limited question of whether conditions under Section 37 are satisfied) from the guilt determination (which will await full trial evidence).[1]

Broader Jurisprudential Significance

The Vivek Kumar judgment crystallizes several important legal principles that are reshaping NDPS bail jurisprudence across Indian courts:

Evidentiary Quality as a Bail Factor: The judgment establishes that while procedural irregularities in evidence collection (absence of independent witnesses, lack of audio-visual documentation) may not be fatal to the prosecution’s case at trial, they legitimately cast doubt on evidentiary credibility and warrant cautious evaluation at the bail stage. This principle reflects contemporary understandings of scientific criminal investigation and the availability of technology that makes audio-visual documentation feasible and expected.[1][7][12]

Primacy of Constitutional Rights: The judgment reaffirms that fundamental constitutional rights under Article 21—particularly the right to life, liberty, and speedy trial—cannot be rendered nugatory by statutory provisions, however stringent. While the legislature may impose conditions on bail through statutes like Section 37, such conditions must yield when their application would result in unconstitutional outcomes, such as indefinite pre-trial detention.[7][9][1]

Section 436A as a Countervailing Provision: The judgment establishes that Section 436A of the CrPC, which mandates release on bail when an undertrial has served specified periods, applies equally to NDPS offenses despite Section 37’s stringency. This application of Section 436A prevents Section 37 from becoming a tool for indefinite detention.[10][9][1][7]

Proportionality in Bail Conditions: The judgment demonstrates judicial sensitivity to proportionality—that is, bail conditions should be calibrated to address legitimate state interests (prevention of offense repetition, witness intimidation, absconding) without imposing unnecessarily onerous restrictions that themselves become punitive.[1]

Conclusion

The Vivek Kumar judgment represents a mature articulation of contemporary bail jurisprudence in NDPS cases, demonstrating that even in the context of serious drug trafficking offenses and stringent statutory provisions, courts must remain faithful to constitutional principles and the administration of justice. The decision does not diminish the state’s legitimate interest in combating the menace of drug trafficking, nor does it suggest that serious drug traffickers will automatically receive bail. Rather, it establishes that bail decisions must engage in careful, particularized analysis of the evidence, the accused’s personal circumstances, trial delays, and procedural irregularities, with due regard for the fundamental right to liberty and speedy trial.

The judgment will likely influence bail determinations not only in Delhi but across Indian jurisdictions, particularly in establishing that mere quantity of contraband, while relevant, does not render bail determinations mechanical or automatic. Courts must remain vigilant custodians of constitutional rights, ensuring that the fight against drug trafficking does not sacrifice the foundational principles of fair trial and proportionate justice. As the Supreme Court observed in Mohd. Muslim, injustice perpetrated through indefinite pre-trial detention is itself a grave social harm that the law must address with the same seriousness with which it addresses drug trafficking.

- 59512122025BA15522025_200703.pdf

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/interpretation-of-section-37-of-the-narcotic-drugs-and-psychotropic-substances-act-1985/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/lawtics/know-your-rights-drug-terror-economic-offences-bail-laws-in-india/

- https://advocatepooja.com/bail-in-ndps-cases-in-india-understanding-the-legal-landscape/

- https://tarungaur.in/mediacenter/how-to-get-bail-in-ndps-cases-ndps-case-bail-explained/

- https://www.courtkutchehry.com/judgements/657555/pdf/

- https://www.verdictum.in/court-updates/high-courts/delhi-high-court/sahil-sharma-alias-maxx-v-state-govt-of-nct-of-delhi-2025dhc10798-lack-of-independent-witnesses-bail-to-ndps-accused-1600301

- https://rawlaw.in/bombay-high-court-grants-bail-under-section-436-a-crpc-prolonged-pre-trial-detention-without-trial-violates-article-21-bail-is-the-rule-jail-is-the-exception/

- https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/01/14/bail-ndps-case-undue-delay-in-trial-unfettered-by-s-37-punjab-haryana-hc/

- https://aklegal.in/mohd-muslim-v-state-nct-of-delhi/

- https://narcoticsindia.nic.in/Judgments/Mohd. Muslim 22.02.2023.pdf

- https://supremetoday.ai/prolonged-incarceration-and-evidentiary-discrepancies-override-section-37-ndps-act-rigors-for-bail-grant-delhi-high-court-INDDEL00000153424

- https://delhihighcourt.nic.in/app/showFileJudgment/SVN22072025BA5522025_175910.pdf

- https://delhihighcourt.nic.in/app/showFileJudgment/SVN28112025BA31212025_203537.pdf

- https://www.devdiscourse.com/article/law-order/3609119-teen-nabbed-with-30kg-of-cannabis-in-delhi-bust

- https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2022/12/31/undertrial-prisoners-cannot-be-detained-in-custody-for-an-indefinite-period-delhi-high-court/

- https://www.ilms.academy/blog/bail-provisions-under-NDPS-act

- https://devgan.in/crpc/section/436A/

- https://delhihighcourt.nic.in/app/showFileJudgment/59503122025BA30682025_211518.pdf

- https://delhihighcourt.nic.in/app/showFileJudgment/75101082025BA16262025_205242.pdf

- https://lawtrend.in/sc-clarifies-bail-principles-under-article-21-and-section-436a-crpc-explains-reverse-burden-in-criminal-trials/