Drafting Dignity: Dr. Ambedkar and the Soul of the Constitution

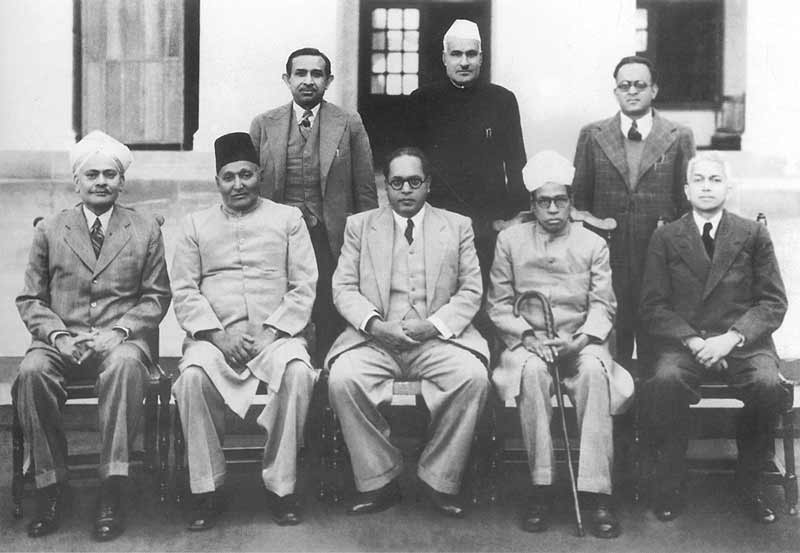

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar’s appointment as Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly on August 29, 1947, marked one of the most transformative moments in India’s constitutional history. Far more than a ceremonial position, this role allowed Ambedkar to embed his vision of social justice, human dignity, and democratic equality into the very fabric of independent India’s foundational document. His work in the Constituent Assembly represents not merely the drafting of legal provisions, but the conscious crafting of a constitutional framework designed to dismantle centuries of oppression and establish a truly egalitarian society.

Members of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constituent Assembly, including chairman Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, circa 1947 commons.wikimedia

The Architect’s Vision: Constitutional Democracy as Social Revolution

Ambedkar approached constitutional drafting with a profound understanding that political democracy without social democracy would remain an empty promise. His vision for the Constitution extended far beyond establishing governmental structures; it sought to create what he termed “associated living” – a society where liberty, equality, and fraternity would form an indissoluble trinity. Unlike many of his contemporaries who viewed the Constitution primarily as a framework for governance, Ambedkar saw it as an instrument of social transformation that would challenge entrenched hierarchies and create opportunities for the marginalized.

This philosophical foundation shaped every aspect of his constitutional work. Ambedkar firmly believed that democracy must permeate not just political institutions but social and economic relationships. In his seminal articulation of this principle, he warned the Constituent Assembly that “political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base social democracy”. This conviction drove his insistence on comprehensive fundamental rights, robust directive principles, and specific provisions targeting centuries-old discriminatory practices.

The Chairman of the Drafting Committee brought to his role an extraordinary combination of personal experience with oppression and scholarly expertise in constitutional law. His education at Columbia University and the London School of Economics had exposed him to diverse constitutional traditions, while his lived experience of caste discrimination provided him with intimate knowledge of the social realities that the Constitution needed to address. This unique perspective enabled him to craft provisions that were both legally sound and socially revolutionary.

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar working on official documents in a formal office setting during his tenure as chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution swarajyamag

The Drafting Process: Leadership Under Pressure

The Constituent Assembly’s decision to elect Ambedkar as Chairman of the Drafting Committee surprised even Ambedkar himself. In his own words, he had entered the Assembly with “no greater aspiration than to safeguard the interest of the Scheduled Castes” and was “greatly surprised when the Assembly elected me to the Drafting Committee” and “more than surprised when the Drafting Committee elected me to be its Chairman”. This appointment, however, proved to be providential, as it placed one of India’s most insightful constitutional thinkers in a position to influence the entire document.

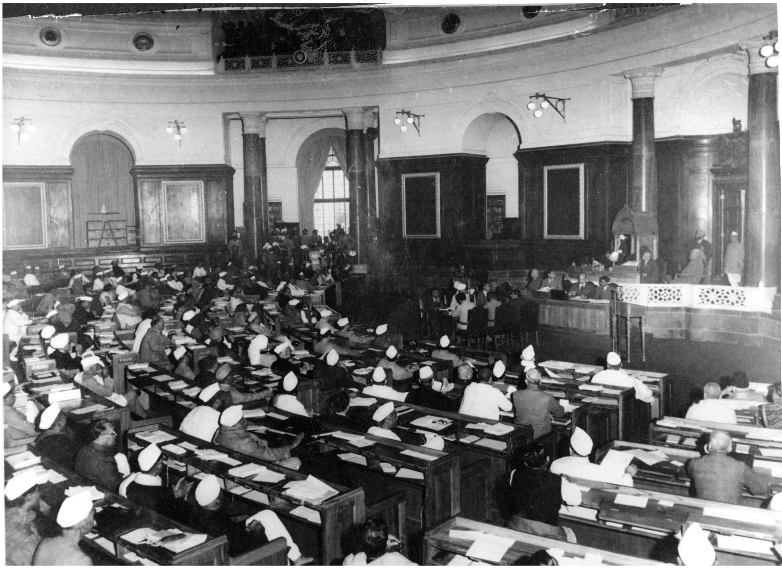

The Drafting Committee worked with remarkable intensity and dedication under Ambedkar’s leadership. From its formation on August 29, 1947, to the submission of the final draft, the Committee sat for 141 days, transforming the initial draft prepared by Constitutional Adviser B.N. Rau from 243 articles into a comprehensive document of 395 articles under the guidance of Ambedkar. Ambedkar’s role extended far beyond administrative oversight; he actively participated in refining language, resolving conceptual conflicts, and ensuring that the Constitution’s various parts formed a coherent whole.

The magnitude of the task cannot be overstated. The Constituent Assembly received approximately 7,635 amendment proposals, of which 2,473 were actually moved and debated. As Chairman of the Drafting Committee, Ambedkar had to defend virtually every provision of the draft Constitution, participating in nearly every major debate and demonstrating encyclopedic knowledge of constitutional law and comparative governance.

Fundamental Rights: The Constitutional Revolution

Perhaps nowhere is Ambedkar’s transformative vision more evident than in the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution. His approach to fundamental rights reflected a sophisticated understanding of both their protective and transformative functions. Rather than merely shielding citizens from state overreach, Ambedkar envisioned fundamental rights as active instruments of social change that would dismantle discriminatory practices and create genuine equality.

The debate over the scope and limitations of fundamental rights revealed Ambedkar’s nuanced constitutional philosophy. Critics argued that the fundamental rights in the draft Constitution were “riddled with so many exceptions that the exceptions have eaten up the rights altogether”. Ambedkar’s response demonstrated his deep understanding of constitutional jurisprudence. He argued that the distinction between fundamental and non-fundamental rights lay not in their absoluteness but in their source – fundamental rights being “the gift of the law” rather than agreements between parties.

Article 14, ensuring equality before law, Article 15, prohibiting discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth, and Article 17, abolishing untouchability, formed the triumvirate of Ambedkar’s constitutional revolution. These provisions, particularly when read together, created a comprehensive framework for challenging social hierarchy and ensuring human dignity.

Article 17 stands as perhaps Ambedkar’s most personal and revolutionary contribution to the Constitution. The provision declaring that “untouchability is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden” represented a direct assault on one of Hinduism’s most entrenched social practices. During the brief but decisive debate on November 29, 1948, the Constituent Assembly unanimously supported this article, though some members sought greater precision in defining “untouchability”. Ambedkar’s decision to keep the definition broad rather than restrictive demonstrated his understanding that constitutional language must be flexible enough to address various forms of social discrimination.

Federal Structure and Parliamentary Democracy

Ambedkar’s contribution to India’s federal structure reflects his sophisticated understanding of the balance between unity and diversity in a vast, pluralistic nation. When presenting the draft Constitution to the Constituent Assembly, he described it as “federal” while acknowledging its unique characteristics. His formulation that the Constitution “establishes a dual polity with the Union at the Centre and the States at the periphery, each endowed with sovereign powers to be exercised in the field assigned to them respectively” created a flexible federal framework suited to Indian conditions.

The federal structure that emerged under Ambedkar’s guidance was neither rigidly federal nor unitary but what he termed a system that “can be both unitary as well as federal according to the requirements of time and circumstances”. This flexibility proved prescient, allowing the Constitution to adapt to various challenges while maintaining democratic governance. In normal times, the system operates federally, but during emergencies, it can function with unitary characteristics.

Ambedkar’s advocacy for parliamentary democracy stemmed from his belief that it provided the best framework for accountability and representation. He argued that parliamentary system offered “daily and periodic assessment of responsibility of the Government” and was more conducive to democratic governance than presidential systems. His vision of the President as a “ceremonial device on a seal by which the nation’s decisions are made known” reflected his commitment to responsible government and ministerial accountability.

Directive Principles: The Constitution’s Social Conscience

The Directive Principles of State Policy, which Ambedkar described as “novel features” of the Indian Constitution, embodied his vision of transformative governance. These principles, contained in Articles 36 to 51, provided a comprehensive roadmap for creating a welfare state that would address India’s massive social and economic inequalities.

Ambedkar’s conception of directive principles reflected his understanding that constitutional mandates alone could not create social transformation. The principles required active state intervention to “promote the welfare of the people by securing and protecting just social order”. Articles 38 and 39, promoting social justice and equitable distribution of resources, directly reflected Ambedkar’s commitment to economic democracy.

The directive principles served multiple functions in Ambedkar’s constitutional framework. They provided constitutional guidance for policy-making, created standards for evaluating government performance, and established the ideological foundation for a welfare state. Most importantly, they complemented fundamental rights by providing the positive obligations that would make constitutional promises meaningful for India’s marginalized populations.

The Constituent Assembly of India in session during the 1940s, where Dr. B.R. Ambedkar played a pivotal role in drafting the Constitution apnagyaan

Challenges and Opposition: Navigating Constitutional Politics

Ambedkar’s tenure as Chairman of the Drafting Committee was not without significant challenges and opposition. His initial skepticism about a Constituent Assembly itself revealed his concerns about the democratic process being dominated by elite interests. In a 1945 speech, he had argued that a Constituent Assembly was “absolutely superfluous” and “a most dangerous project, which may involve this country in civil war”. His fear that constitutional decision-making would be captured by narrow interests proved prescient in many ways.

Within the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar faced criticism from various quarters. Some members, like K.T. Shah, challenged the lack of specific definitions in constitutional provisions, arguing that undefined terms could be exploited by “busybodies and lawyers”. Others criticized what they saw as Western influence in the Constitution, arguing that it was “un-Indian” and surrendered to Western values.

Ambedkar’s response to such criticisms demonstrated both his diplomatic skills and his principled commitment to constitutional excellence. Rather than dismissing opposition voices, he acknowledged their contributions to the constitutional discourse. In his final speech, he specifically thanked the “rebels” in the Assembly – members like Kamath, Deshmukh, Sidhva, and others – for enriching the debates and preventing the Assembly from becoming merely “a gathering of yes men”. This gracious acknowledgment of dissent reflected his deep commitment to democratic deliberation.

Perhaps the most significant challenge came from conservative elements who opposed the Constitution’s progressive provisions, particularly those related to social reform. The subsequent controversy over the Hindu Code Bill, which Ambedkar championed after independence, revealed the persistent opposition to his vision of social transformation. By 1953, this opposition had led to his profound disillusionment with Indian democracy, culminating in his stark assessment that democracy would not work in India due to the incompatibility between parliamentary democracy and India’s social structure.

Constitutional Philosophy: Democracy as a Way of Life

Central to understanding Ambedkar’s role in the Constituent Assembly is his sophisticated philosophy of constitutional democracy. For Ambedkar, democracy was not merely a political system but “a way of life which recognizes liberty, equality and fraternity as the principles of life”. This trinity – borrowed from the French Revolution but infused with his own understanding of social oppression – formed the ideological core of his constitutional vision.

Ambedkar’s emphasis on fraternity distinguished his democratic theory from purely individualistic or majoritarian conceptions of democracy. He argued that liberty and equality without fraternity would remain incomplete, as fraternity provided the social solidarity necessary for democratic functioning. This insight proved particularly relevant for India’s diverse and hierarchical society, where social divisions threatened to undermine democratic institutions.

His famous warning in the final speech to the Constituent Assembly about entering “a life of contradictions” – having equality in politics while maintaining inequality in social and economic life – reflected his deep understanding of democracy’s requirements. Ambedkar recognized that constitutional provisions alone could not eliminate social inequalities, but he believed that a properly crafted Constitution could provide the framework and momentum for gradual social transformation.

The Constitution’s success, in Ambedkar’s view, would depend not on its textual provisions but on the character of those charged with implementing it. His observation that “however good a Constitution may be, it is sure to turn out bad because those who are called to work it, happen to be a bad lot” emphasized the crucial role of political culture and leadership in constitutional success.

Legacy and Impact: The Constitution as Living Document

Ambedkar’s work in the Constituent Assembly created a constitutional framework that has endured for over seven decades, adapting to changing circumstances while maintaining its core commitments to justice, liberty, and equality. The Constitution’s emphasis on fundamental rights, federal flexibility, and directive principles has enabled it to respond to diverse challenges while preserving democratic governance.

The transformative impact of Ambedkar’s constitutional vision is evident in the gradual expansion of rights and opportunities for marginalized communities. The constitutional provisions he championed – from the abolition of untouchability to reservations for scheduled castes and tribes – have created unprecedented opportunities for social mobility and political participation. While complete social transformation remains a work in progress, the constitutional foundation he established has made possible advances that would have been inconceivable under previous legal frameworks.

Contemporary constitutional interpretation continues to draw on Ambedkar’s vision and language. Supreme Court decisions regularly invoke the constitutional principles he articulated, particularly the commitment to dignity, equality, and social justice. The expansion of fundamental rights through judicial interpretation reflects the dynamic quality that Ambedkar built into the constitutional text.

Perhaps most significantly, Ambedkar’s constitutional philosophy has provided a framework for ongoing struggles for social justice. His understanding of the Constitution as an instrument of transformation rather than merely a procedural document continues to inspire movements for equality and human rights. The constitutional language he crafted – emphasizing human dignity, social justice, and inclusive democracy – remains a powerful resource for those seeking to expand democratic participation and challenge persistent inequalities.

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of Constitutional Vision

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s role in the Constituent Assembly transcended the technical work of constitutional drafting to encompass a visionary reimagining of Indian society and governance. His leadership of the Drafting Committee produced not merely a legal document but a transformative charter that challenged centuries of social hierarchy and established unprecedented commitments to human dignity and equality.

The Constitution that emerged under Ambedkar’s guidance reflected his profound understanding that successful democracy required more than political procedures; it demanded social solidarity, economic justice, and cultural transformation. His insistence on fundamental rights that actively challenged discrimination, directive principles that mandated state action for social welfare, and federal structures that balanced unity with diversity created a framework uniquely suited to India’s complex realities.

The challenges Ambedkar faced and the opposition he encountered revealed the revolutionary nature of his constitutional vision. By embedding principles of social justice and human dignity into India’s foundational law, he created possibilities for transformation that continue to inspire and guide democratic struggles today. His warning about the contradictions between political equality and social inequality remains as relevant now as it was in 1949, challenging each generation to work toward the fuller realization of constitutional promises.

Today, as India continues to grapple with questions of justice, equality, and democratic governance, Ambedkar’s constitutional legacy provides both inspiration and guidance. His vision of the Constitution as a living document committed to human dignity and social transformation continues to offer resources for building a more inclusive and egalitarian democracy. The soul of the Constitution that Ambedkar helped craft remains a powerful force for justice and equality, embodying his enduring faith in democracy’s potential to create a society worthy of human dignity.

[…] “Drafting Dignity: Ambedkar and the Soul of the Constitution” […]