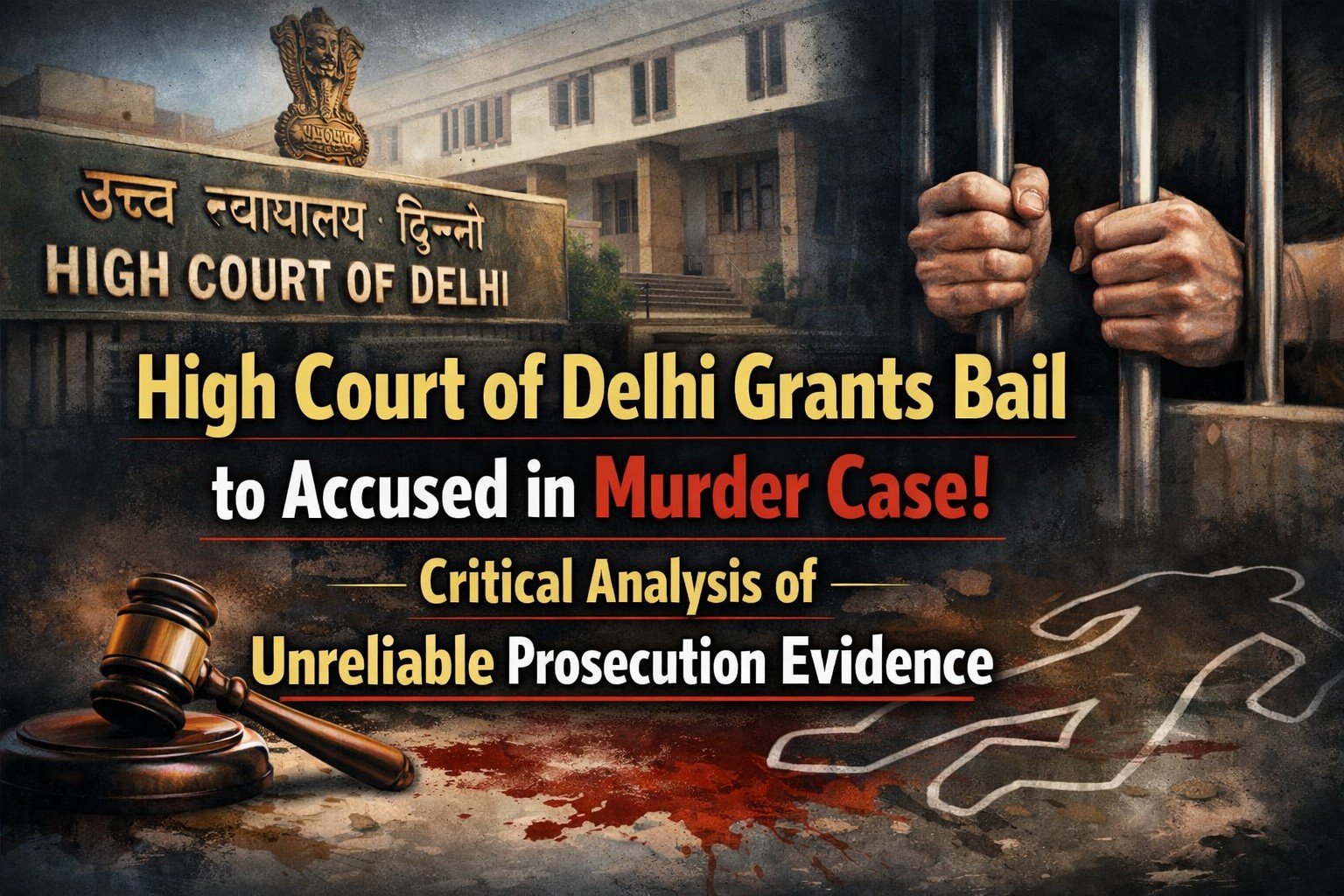

High Court of Delhi Grants Bail to Accused in Murder Case: Critical Analysis of Unreliable Prosecution Evidence

Overview

In a significant judgment delivered on January 12, 2026, Justice Girish Kathpalia of the High Court of Delhi granted regular bail to Mohsin @ Abrar in Bail Application 4135/2025, accused of murder under Sections 302/120B/34 of the Indian Penal Code and offences under the Arms Act. The order provides an instructive case study on the critical importance of robust, reliable evidence in criminal proceedings, particularly in cases involving serious offences like murder. The court’s decision demonstrates that despite the gravity of allegations, weak corroborating evidence and scientific inconsistencies warrant the release of an accused on bail while trial proceedings continue.[1]

Case Background and Charges

Mohsin @ Abrar faced allegations of murder in connection with FIR No. 79/2019 registered at PS Krishna Nagar in Delhi. According to the prosecution narrative, the accused fired a country-made pistol at the deceased, resulting in fatal injuries. The case began as a “blind FIR” – a common situation in criminal law where an incident is reported but initial eyewitnesses are not immediately present at the scene. The injured person was taken to the hospital where he subsequently succumbed to his injuries.[1]

The prosecution charged that the accused acted in conspiracy with three other alleged assailants, and claimed that the entire incident was captured on CCTV footage. The allegation further rested on the identification of the accused by two purported eyewitnesses who allegedly named him as one of the assailants involved in the shooting. The accused was in continuous police custody from April 26, 2019, throughout the investigation and trial phases, though he was briefly released on COVID-related bail during the pandemic.

Prosecution’s Evidence and Arguments

The prosecution presented three primary pieces of evidence against the accused. First, eyewitness identification: Two witnesses examined during the investigation and trial allegedly identified the accused as one of the assailants responsible for firing the fatal shots. Second, CCTV footage: The prosecution claimed that the entire incident had been captured on surveillance cameras and that the eyewitnesses had identified the accused from this footage. Third, the refusal to participate in a Test Identification Parade (TIP): The accused declined to undergo a TIP, which the prosecution argued made dock identification by eyewitnesses more significant as corroborating evidence.[1]

The prosecuting counsel, Mr. Amit Ahlawat, argued that the gravity of the alleged offence – murder – warranted the accused’s continued detention. He presented the CCTV footage before the court, contending that it clearly captured the alleged offence. However, the prosecution’s case, despite its apparent strength on paper, suffered from critical evidentiary deficiencies.

The Court’s Critical Analysis of Evidence

Justice Kathpalia conducted a meticulous examination of the prosecution’s evidence and identified several fatal weaknesses that undermined the credibility of the case. The judge’s analysis, delivered in an oral judgment, reveals a sophisticated understanding of evidence law and the standards required for linking an accused to serious criminal charges.

Inadequacy of CCTV Footage

The most striking aspect of the judgment concerns the CCTV footage, which formed the cornerstone of the prosecution’s case. After the footage was played in court, the learned prosecutor, exercising fairness and professional responsibility, did not dispute that the CCTV footage did not depict the actual incident of firing. More critically, the footage did not clearly show the faces of the alleged assailants. As the court observed: “Where faces of the alleged assailants are not clearly depicted, identity of any of the alleged assailants on the basis of that footage would be a suspect, to say the least at this stage.”[1]

This observation is legally significant because identification is a cornerstone of criminal proof. When a person’s identity cannot be clearly established from video footage, relying on such footage becomes problematic, particularly when the prosecution claims CCTV recording as primary evidence. The prosecutor further conceded that the CCTV footage did not even depict the presence of either of the two eyewitnesses at the spot of the incident, raising serious questions about the veracity of their claimed presence at the scene.[1]

Forensic Evidence Contradiction

The judgment highlighted a critical forensic discrepancy that the prosecution could not overcome. The bullet retrieved from the deceased’s body did not correspond to the country-made pistol allegedly used by the accused, according to the Forensic Science Laboratory (FSL) report. This is a significant finding because it suggests that even if the accused committed some act of violence, the weapon he allegedly carried was not the one that caused the fatal injury.[1]

The court noted that “This point is not disputed by the learned APP after examining the FSL report,” indicating that the prosecution had no counter-argument to this critical forensic finding. In criminal law, forensic evidence, being objective and scientific in nature, carries substantial weight. A mismatch between the alleged weapon and the bullet extracted suggests either that the accused was framed or that he was not directly involved in the fatal shooting.[1]

Weaknesses in Eyewitness Identification

The court synthesized these findings to conclude that the only evidence connecting the accused to the crime was based on identification by eyewitnesses from CCTV footage that did not clearly show faces or the firing incident itself. The defense counsel had argued that such evidence was unreliable, and the court implicitly agreed with this assessment. The refusal to participate in a TIP, which the prosecution had highlighted, loses its significance when the corroborating evidence itself is suspect.[1]

Mitigating Factors Considered

Beyond the evidentiary deficiencies, the court considered several other factors favoring bail:

Duration of Custody: The accused had been imprisoned for nearly seven years (from April 26, 2019) at the time of judgment. Such prolonged detention, particularly when the trial is far from completion, constitutes a compelling humanitarian reason for bail consideration.[1]

Status of Co-Accused: The defense counsel highlighted that two of the four alleged assailants had already been granted bail by the High Court itself, suggesting that even those more directly implicated had been freed pending trial. Moreover, one alleged assailant was a Child in Conflict with Law, whose case would be handled under special juvenile justice procedures. This inconsistency in treating co-accused was a relevant consideration.[1]

Trial Timeline: At the time of bail application, only two of approximately 32 witnesses had been examined in trial. This indicated that the trial was in its nascent stages, and completion was nowhere in the immediate future. Keeping an accused in custody for years during a prolonged trial, particularly when evidence is weak, raises constitutional concerns.[1]

Criminal Record: The prosecution conceded that the accused had no prior criminal antecedents, suggesting he posed no risk as a repeat offender or habitual criminal.[1]

The Court’s Reasoning and Bail Grant

Drawing together these threads, Justice Kathpalia articulated the essence of the prosecution’s case in paragraph 9 of the judgment: “the offence concerned was a blind offence in which involvement of the accused/applicant is alleged solely on the basis of identification by the alleged eyewitnesses through CCTV footage, which does not depict faces clearly and according to the FSL, the bullet retrieved from the dead body was not fired from the country-made pistol allegedly used by the accused/applicant.”[1]

This synthesis demonstrated that the prosecution’s entire case rested on questionable pillars. The court found the situation untenable: an accused imprisoned for nearly seven years based on evidence that was demonstrably unreliable and contradicted by scientific analysis.

The court granted bail subject to the accused furnishing a personal bond of Rs. 10,000 with one surety in the like amount. This was a relatively standard bail condition, reflecting that while the court found reason to release him, it still required basic assurances.[1]

Important Judicial Caution

The judgment includes a significant cautionary note: “As a matter of cautious rider, it is made clear that none of the observations made above shall be read at the time of final decision of the trial.” This rider is important because it clarifies that the judge’s observations on the weakness of evidence at the bail stage are provisional and exploratory, made in the context of the specific bail application. These observations would not prejudge the trial court’s ultimate verdict.[1]

This distinction is crucial in criminal jurisprudence – bail decisions and final verdict decisions operate at different thresholds. A bail decision asks whether there is a reasonable case to detain the accused pending trial; it does not require proof beyond reasonable doubt. Conversely, a conviction requires satisfaction of guilt beyond reasonable doubt. The judge’s preliminary assessment of evidence weakness does not predetermine the trial’s outcome.

Legal and Procedural Significance

This judgment exemplifies several important principles in Indian criminal law and bail jurisprudence:

Scrutiny of Evidence at Bail Stage: Bail courts are not mere formality-following bodies; they must critically examine evidence and cannot grant bail based on unsubstantiated allegations. The court’s detailed engagement with CCTV footage and forensic reports demonstrates this responsibility.

Limits of Circumstantial Evidence: When an accused’s guilt rests entirely on circumstantial evidence—here, eyewitness identification from unclear footage—courts must ensure that the circumstantial evidence is of the highest quality and not merely speculative.

Forensic Evidence Primacy: The court’s reliance on FSL findings that contradicted the prosecution narrative highlights the importance of scientific evidence in modern criminal law. When such evidence exculpates or creates doubt, it must be given substantial weight.

Proportionality in Detention: Prolonged custody without corresponding strength in evidence violates principles of human rights and due process, enshrined in Articles 21 and 22 of the Indian Constitution.

Conclusion

The judgment of Justice Girish Kathpalia stands as a reminder that the criminal justice system, while addressing serious crimes like murder, must not lose sight of the fundamental principle that the burden of proof rests on the State and that evidence must be reliable and credible. The case of Mohsin @ Abrar illustrates how weak prosecution evidence, even when dressed up with eyewitness accounts and video footage, cannot sustain the deprivation of liberty without stronger corroboration.

The bail grant does not mean the accused is innocent or will necessarily be acquitted at trial. However, it reflects the court’s assessment that the case against him, as currently constituted, is insufficient to warrant continued imprisonment while the trial proceeds. This judgment serves as an important precedent for trial courts and practitioners handling criminal matters involving questionable evidence and demonstrates that appellate courts will not hesitate to intervene when lower courts overlook evidentiary deficiencies that justify bail.

![Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [1978] 2 SCR 621: A Watershed Moment in Indian Constitutional Jurisprudence](https://www.infipark.com/articles/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Image-Feb-18-2026-10_47_59-AM-218x150.jpg)