Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025: Revolutionary Metal-Organic Frameworks Transform Molecular Architecture

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to three pioneering scientists whose groundbreaking work has fundamentally transformed our understanding of molecular architecture and porous materials. Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University (Japan), Richard Robson of the University of Melbourne (Australia), and Omar M. Yaghi of UC Berkeley (USA) share this prestigious recognition for their development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), a revolutionary class of materials that promises to address some of humanity’s most pressing challenges, from climate change to water scarcity. [1][2][3]

Nobel Prize medal for Chemistry

Foundation of a Revolutionary Field

Richard Robson: The Pioneering Vision

The journey toward MOFs began in 1989 when Richard Robson, working at the University of Melbourne, conducted a transformative experiment that would reshape modern chemistry. Born in Glusburn, Yorkshire, in 1937, Robson completed his doctorate at Oxford University before establishing his career in Australia. His inspiration came from an unexpected source: creating wooden models of crystalline structures for undergraduate lectures in 1974. This experience led him to wonder whether specially designed molecules could similarly assemble themselves into ordered structures. [1][2][4][5][6]

Robson’s breakthrough came when he combined positively charged copper ions with a four-armed organic molecule, creating the first stable diamond-like crystal structure with large internal cavities. This pioneering work, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in 1989, laid the foundation for an entirely new field of chemistry. However, his initial constructions were unstable and prone to collapse, requiring further innovation to realize their full potential. [2][7][1]

Susumu Kitagawa: Discovering Dynamic Properties

Building upon Robson’s foundational work, Susumu Kitagawa emerged as a transformative figure in the development of MOF chemistry. Born in Kyoto in 1951, Kitagawa obtained his PhD from Kyoto University in 1979 and has spent his career advancing coordination chemistry. His seminal contribution came in 1997 when he demonstrated that coordination polymers could function as stable porous materials capable of gas adsorption—a discovery that established the viability of MOFs as functional materials. [8][9][10][11]

Kitagawa’s most revolutionary insight was recognizing that MOFs could be flexible or “soft” materials, unlike traditional rigid porous substances like zeolites. Between 1992 and 2003, he made a series of groundbreaking discoveries showing that gases could flow in and out of MOF constructions and that these frameworks could dynamically respond to external stimuli. His work introduced the concept of “soft porous crystals” that could adapt their structure in response to temperature, pressure, or chemical environment. [2][9][10][12]

Omar Yaghi: Engineering Stability and Design

The third laureate, Omar M. Yaghi, brought crucial stability and rational design principles to MOF development. Born in 1965 in Amman, Jordan, to Palestinian refugee parents, Yaghi’s journey to scientific excellence represents a remarkable story of perseverance and determination. Growing up in a single room shared with livestock, without electricity or running water, Yaghi moved to the United States at age 15 to pursue his education. [13][14][15]

After completing his PhD at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1990, Yaghi made his breakthrough contribution by creating highly stable MOFs and demonstrating that they could be systematically designed and modified to achieve specific properties. His work between 1992 and 2003 established the principles of “reticular chemistry”—the precise stitching of molecular building blocks into extended crystalline frameworks. Yaghi’s innovations made it possible to rationally design MOFs for specific applications, transforming the field from accidental discovery to deliberate engineering.[2][14][16]

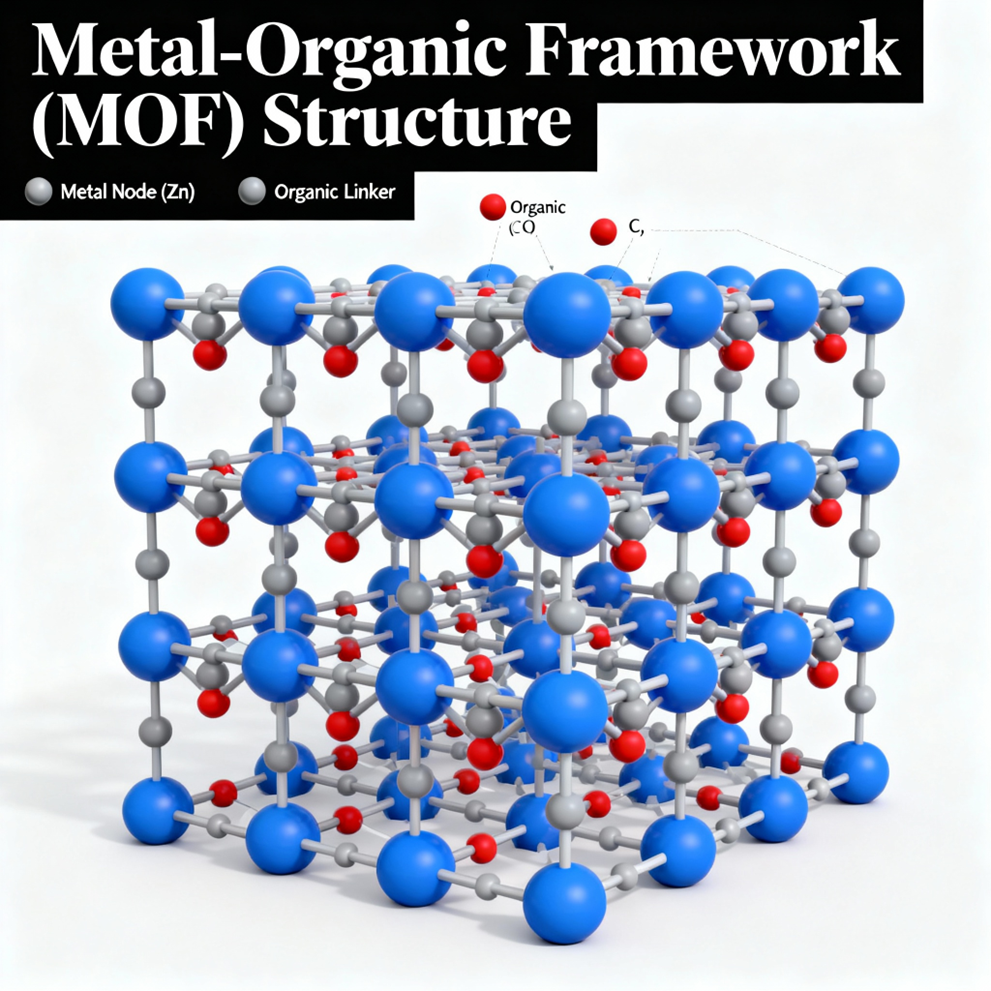

Metal-organic framework molecular structure

Understanding Metal-Organic Frameworks

Structural Architecture

MOFs represent a unique class of hybrid organic-inorganic crystalline materials formed by the coordination of metal ions or clusters with organic ligands. The structure consists of metal nodes that function as cornerstones, connected by long organic molecules acting as linkers or “struts”. This dual nature creates extended three-dimensional networks with precisely controlled pore sizes and exceptionally high surface areas—some MOFs exhibit surface areas exceeding 7,000 square meters per gram. [2][17][18]

The remarkable feature of MOFs lies in their tunability. By varying the metal centers and organic linkers, chemists can design frameworks with specific properties tailored for particular applications. The resulting materials contain large internal cavities that remain stable even after removal of guest molecules, creating permanent porosity that can be exploited for various functions. [17][2]

Unique Properties and Advantages

What distinguishes MOFs from traditional porous materials like zeolites or activated carbon is their unprecedented customizability and multifunctionality. The modular nature of MOF construction allows for the integration of multiple functions within a single material. The organic linkers can incorporate functional groups for specific molecular recognition, while the metal nodes can provide catalytic activity or electronic properties. [19][18]

MOFs also exhibit remarkable structural diversity, with over 90,000 different MOF structures now reported in the literature. This vast library of materials provides chemists with an enormous toolkit for addressing specific challenges. The ability to create flexible or “breathing” MOFs, as demonstrated by Kitagawa, adds another dimension of functionality, allowing these materials to adapt dynamically to changing conditions.[2][9][12]

Revolutionary Applications

Water Harvesting from Desert Air

One of the most striking applications of MOFs is their ability to harvest water from extremely arid environments. Yaghi’s team has developed MOF-based devices capable of extracting water from desert air with relative humidity as low as 9-36%. In field tests conducted in Death Valley, California—one of the world’s driest locations—MOF harvesters produced 210-285 grams of water per kilogram of MOF material per day using only ambient sunlight. [20][21][22]

The water harvesting mechanism exploits the unique properties of MOFs to capture water vapor at night when humidity is slightly higher, then release it during the day when solar heating raises the temperature. The collected water meets national drinking standards and represents a breakthrough for addressing water scarcity in arid regions. These devices operate passively with no energy input aside from ambient sunlight, making them particularly suitable for remote locations. [21][22][20]

MOF water harvesting device in desert environment

Environmental Remediation and PFAS Removal

MOFs have emerged as powerful tools for environmental cleanup, particularly for removing persistent pollutants like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from water. These “forever chemicals” have contaminated water supplies globally and are extremely resistant to degradation. MOF-based systems can selectively capture PFAS through electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and fluorophilic interactions. [23][24][25]

Recent research has demonstrated that specially designed fluorinated MOFs can achieve enhanced PFAS removal efficiency, with some systems maintaining over 90% recovery rates through multiple regeneration cycles. The ability to tailor MOF surface chemistry allows for the development of materials that selectively target specific PFAS compounds while leaving beneficial substances in water unchanged. [24][25][26][23]

Carbon Capture and Climate Solutions

The climate crisis has made carbon dioxide capture and storage a critical technological need, and MOFs offer promising solutions. Their high surface areas and tunable pore sizes make them ideal for selective CO₂ adsorption from industrial emissions or even directly from ambient air. MOFs can be designed to preferentially bind CO₂ over other gases, enabling efficient separation processes. [27][17][28]

Advanced MOF systems are being developed not just for carbon capture but for carbon utilization, converting captured CO₂ into useful chemicals and fuels. This approach could transform carbon emissions from waste products into valuable resources, supporting the transition to a circular carbon economy. [19][27]

Pharmaceutical and Medical Applications

The biomedical field has embraced MOFs for drug delivery and therapeutic applications. The porous structure of MOFs allows for the encapsulation of pharmaceutical compounds, protecting them from degradation and enabling controlled release. The biocompatibility of certain MOFs, combined with their ability to be functionalized with targeting molecules, makes them attractive candidates for precision medicine. [27][19][29]

MOFs are also being explored as biosensors capable of detecting trace amounts of biological molecules, toxins, or drugs in complex biological samples. Their high surface area and tunable chemistry enable the development of highly sensitive and selective detection systems for medical diagnostics. [19][27]

Scientific Impact and Recognition

Research Proliferation and Citation Impact

The development of MOFs has generated an explosion of scientific research, with over 9,000 papers on porous materials now published annually. The three laureates collectively have authored hundreds of scientific articles with tens of thousands of citations, establishing MOFs as one of the most rapidly growing fields in materials science. Kitagawa alone has published over 800 scientific articles with more than 100,000 citations, while Yaghi has been recognized as one of the most highly cited chemists worldwide. [8][30][11][16]

The field’s growth reflects not just academic interest but practical significance. Industrial applications are already emerging, with chemical companies producing MOF materials for gas purification, storage, and transportation. The combination of fundamental scientific innovation and practical applications exemplifies the Nobel Committee’s recognition of research that provides “the greatest benefit to humankind”. [2][10]

Global Recognition and Awards

Prior to their Nobel Prize recognition, all three laureates had received numerous prestigious awards acknowledging their contributions to chemistry. Kitagawa received the Japan Academy Prize, the Wolf Prize in Chemistry, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Yaghi was awarded multiple American Chemical Society honors and became a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. Robson was elected a Fellow of both the Australian Academy of Science and the Royal Society. [8][4][9][5][14]

The international nature of this collaboration—spanning Japan, Australia, and the United States—exemplifies the global character of modern scientific research and the importance of international cooperation in addressing worldwide challenges. [7]

Personal Journeys and Inspiration

Omar Yaghi: From Refugee to Nobel Laureate

Perhaps the most inspiring aspect of this year’s chemistry Nobel is Omar Yaghi’s remarkable personal journey. Born to Palestinian refugee parents who had fled Gaza in 1948, Yaghi grew up in extreme poverty in Jordan. His family lived in a single room without electricity or running water, sharing their space with livestock. His parents could barely read or write, yet they encouraged his education.[13][14][31][15]

At age 15, Yaghi moved alone to the United States to pursue his education, supporting himself by bagging groceries and mopping floors while attending community college. His discovery of a book about molecules at age 10 had sparked a lifelong passion for chemistry. “Science is the greatest equalizing force in the world,” Yaghi reflected upon winning the Nobel Prize, emphasizing how education and scientific opportunity can transcend economic and social barriers.[31][32][16][13]

International Collaboration and Scientific Legacy

The success of MOF development demonstrates the power of international scientific collaboration. While the three laureates worked independently on different aspects of the problem, their research built upon and enhanced each other’s discoveries. This collaborative spirit, spanning different continents and cultures, exemplifies how science transcends national boundaries to address global challenges.[2][33]

The Nobel Committee’s recognition of this work acknowledges not just past achievements but future potential. With tens of thousands of different MOFs now synthesized and applications ranging from environmental remediation to medical devices, the field continues to expand rapidly. The principles established by these three pioneers provide a foundation for addressing challenges in energy storage, sustainable chemistry, and materials science for decades to come.[19][18][29][2]

Future Prospects and Challenges

Scaling and Commercialization

While MOFs have demonstrated remarkable laboratory performance, scaling up production for industrial applications remains a significant challenge. The synthesis of MOFs often requires carefully controlled conditions and expensive organic linkers, making large-scale manufacturing costly. However, advances in synthetic methods and the development of more economically viable synthetic routes are beginning to address these limitations. [27][19][29]

Several companies are already commercializing MOF-based products for gas storage and purification applications, demonstrating the feasibility of industrial-scale production. As manufacturing processes improve and costs decrease, MOFs are expected to find broader application in areas such as automotive emission control, natural gas storage, and industrial separations. [18][10]

Emerging Applications and Research Frontiers

The future of MOF research lies in developing multifunctional materials that can simultaneously address multiple challenges. For example, researchers are working on MOFs that can capture CO₂ while generating useful chemicals, or materials that can purify water while producing energy. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is also accelerating MOF design, enabling the prediction of optimal structures for specific applications. [24][25][19][18]

Sustainable MOF development represents another important frontier, focusing on the use of renewable raw materials and environmentally friendly synthetic processes. Bio-derived organic linkers and earth-abundant metal centers are being explored as alternatives to expensive and scarce materials. [19][29]

Conclusion

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry celebrates a transformative scientific achievement that exemplifies the power of fundamental research to address global challenges. The development of metal-organic frameworks by Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar Yaghi has created an entirely new class of materials with unprecedented versatility and functionality. [1][2][3]

Their work demonstrates how basic scientific curiosity—Robson’s interest in molecular self-assembly, Kitagawa’s exploration of flexible coordination polymers, and Yaghi’s pursuit of rationally designed frameworks—can evolve into technologies with profound implications for society. From harvesting water in the world’s most arid regions to capturing carbon dioxide from industrial emissions, MOFs represent a powerful toolkit for addressing climate change, environmental pollution, and resource scarcity. [2][20][21][25][6]

The personal stories of the laureates, particularly Yaghi’s journey from refugee to Nobel Prize winner, inspire confidence in the democratizing power of education and scientific opportunity. Their international collaboration demonstrates how scientific progress transcends national boundaries and cultural differences to create solutions for shared human challenges. [13][31][32]

As MOF research continues to expand and mature, the foundational work of these three chemists provides a lasting legacy that will continue generating innovations for decades to come. Their achievement represents not just a scientific milestone but a testament to the transformative power of curiosity-driven research and international scientific cooperation. [19][18][2]

- https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/nobel-prize-in-chemistry-2025-susumu-kitagawa-richard-robson-omar-yaghi-win-nobel-prize-in-chemistry-9417395

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/press-release/

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/summary/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Robson_(chemist)

- https://royalsociety.org/people/richard-robson-35839/

- https://www.chem.ox.ac.uk/article/nobel-prize-in-chemistry-for-oxford-alumnus-richard-robson

- https://www.acs.org/pressroom/newsreleases/2025/october/acs-president-comments-on-award-of-2025-nobel-prize-in-chemistry.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susumu_Kitagawa

- https://royalsociety.org/people/susumu-kitagawa-36227/

- https://kuias.kyoto-u.ac.jp/e/profile/kitagawa/

- https://www.icems.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/people/1422/

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/popular-information/

- https://gulfnews.com/world/americas/from-palestinian-refugee-to-nobel-glory-omar-yaghis-incredible-journey-1.500299240

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omar_M._Yaghi

- https://www.trtworld.com/article/479f76df4a99

- https://www.instagram.com/reel/DPj8K3YAfor/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metal–organic_framework

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/gch2.202300244

- https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2020/na/d0na00184h

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-32642-0

- http://yaghi.berkeley.edu/pdfPublications/23MOFwaterdevice.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7453559/

- https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2025/mr/d5mr00043b

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.iecr.5c01041

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.5c00902

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9804497/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9320690/

- https://shop.nanografi.com/blog/what-are-the-applications-of-metal-organic-frameworks/

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c05310

- https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/nobel-prize-in-chemistry-winner-2025-who-are-the-winners-check-their-education-career-details-awards-and-achievements-1820003187-1

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/us-scientist-of-palestinian-descent-among-three-winners-of-nobel-prize-for-chemistry/

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/10/08/nobel-prize-palestinian-omar-yaghi-chemistry/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/10/8/nobel-prize-in-chemistry-awarded

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025_Nobel_Prize_in_Chemistry

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/nobel-prize-in-chemistry-2025-to-susumu-kitagawa-richard-robson-and-omar-yaghi-101759913276620.html

- https://www.acs.org/pressroom/newsreleases/2025/october/2025-chemistry-nobel-prize-acs-president-available-for-comment.html

- https://www.reuters.com/science/kitagawa-robson-yaghi-win-2025-nobel-prize-chemistry-2025-10-08/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/2025-chemistry-nobel-goes-to-molecular-sponges-that-purify-water-store/

- https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-sci-tech/chemistry-nobel-2025-created-mof-useful-10295305/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0d02ONEXWkc

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nobel_Prize_in_Chemistry

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC9H9r543xQ

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.0c00678

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666998623000789

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590238522004428

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S095965262302454X

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0043135424011758

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213343723013076

- https://www.science.org/content/article/crystalline-nets-harvest-water-desert-air-turn-carbon-dioxide-liquid-fuel

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2025/robson/facts/

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.9b00408

- https://theconversation.com/an-australian-chemist-just-won-the-nobel-prize-heres-how-his-work-is-changing-the-world-267094

- https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/profile/15996-richard-robson