Shailendra: The People’s Poet Who Transformed Hindi Cinema

Shailendra stands as one of the most influential lyricists in the history of Hindi cinema, a visionary poet whose simple yet profound words touched the hearts of millions and became the voice of the common man. Born Shankardas Kesarilal on August 30, 1923, in Rawalpindi, Punjab (now in Pakistan), this extraordinary wordsmith transcended his humble origin to become what filmmaker Raj Kapoor lovingly called his “Pushkin”—after the legendary Russian poet [1][2].

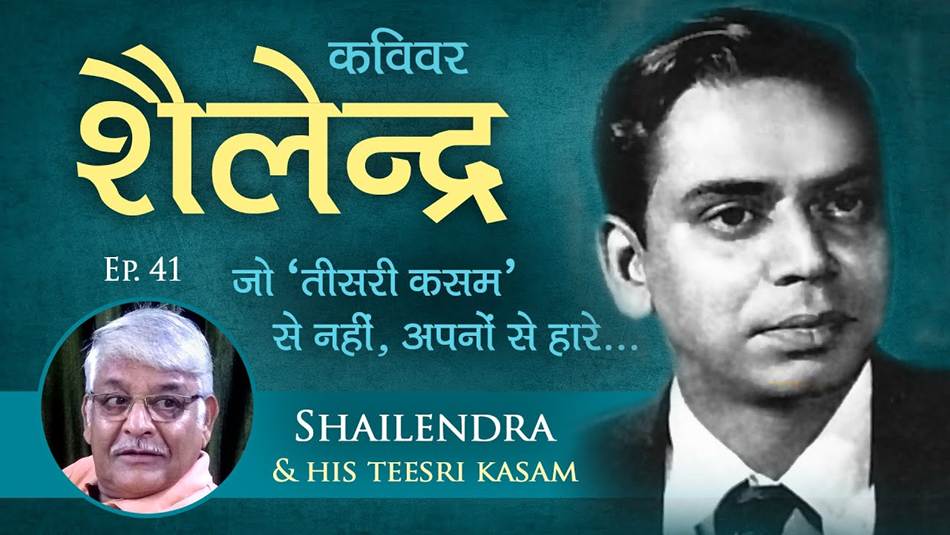

Shailendra, the famous lyricist, and poet, known for his contribution to the film ‘Teesri Kasam’.

His journey from a railway workshop welder to Hindi cinema’s most celebrated lyricist represents not just personal triumph but a revolutionary transformation in how Indian films communicated with their audiences. Through his 18-year career, Shailendra penned nearly 800 songs for 171 films, creating a body of work that seamlessly blended Marxist ideology with humanist philosophy, simplicity with profundity, and the struggles of the downtrodden with universal emotions [3][4].

Early Life and Formative Struggles

Shailendra’s early life was marked by profound hardships that would later shape his worldview and artistic sensibility. Born into a financially weak family whose traditional occupation was leather tanning, he experienced firsthand the cruel realities of caste discrimination and economic marginalization [1][5]. His ancestors originally hailed from Akhtiarpur in Arrah district of Bihar, where most workers were agricultural laborers struggling for survival [4].

The family’s financial difficulties forced multiple relocations—first from Bihar to Rawalpindi, where his father found work as a military contractor, and later in 1931, when Shailendra was just eight years old, to Mathura, Uttar Pradesh [1][4]. These early years were scarred by devastating personal losses: he lost his mother and sister at a young age, tragedies that created a void in his childhood and instilled in him a deep sensitivity to human suffering [1][4].

In Mathura, where he spent 16 formative years, young Shailendra faced the bitter sting of caste-based discrimination. He was denied the simple childhood pleasure of playing hockey because of his Downtrodden identity [4]. These experiences of exclusion and prejudice planted the seeds of his lifelong commitment to social justice and his eventual alignment with communist ideology [5].

Despite financial constraints that often left the family struggling to afford basic necessities—including medical treatment for his dying sister—Shailendra’s intellectual curiosity remained undiminished [4]. Every evening after school, he would visit the A.H. Wheeler bookstore in Mathura, voraciously reading every book he could access, transforming himself into a remarkably well-read individual [4]. His natural poetic talents began emerging during these years, with his poems being regularly published in an Agra magazine [4].

Shailendra engaged in handwritten lyric composition in a traditional setting.

The Railway Years and Political Awakening

In 1947, Shailendra’s career took a pivotal turn when he joined the Indian Railways as a welding apprentice at the Matunga workshop in Mumbai [1][2]. This period marked not just his entry into the workforce but also his political and artistic awakening. The bustling metropolis, with its stark contrasts between wealth and poverty, further deepened his understanding of social inequalities.

It was during his railway employment that Shailendra became actively involved with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India [5][2]. IPTA provided him with a platform to express his revolutionary ideals through poetry and songs. His involvement with this progressive organization shaped his artistic voice, leading him to create stirring compositions that became rallying cries for the oppressed.

One of his most powerful IPTA compositions reflects his revolutionary fervor: “Buri hai aag pet ki, Bure hain dil ke daag ye, Na dab sakenge, Ekdin Danenge inqlab ye” (The fire of hunger is evil, the stains on the heart are evil, they cannot be suppressed, one day they will spark revolution) [2]. Another famous slogan that originated from his pen—“Har zor-zulm kee takkar mein, hartal hamara nara hai” (Strike is our weapon against every atrocity, every excess)—continues to resonate in protest movements even today [5][6].

Vintage photograph of women from the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) in traditional sarees, reflecting the cultural era linked to lyricist Shailendra.

The Fateful Meeting with Raj Kapoor

The trajectory of Shailendra’s life changed dramatically when he encountered Raj Kapoor at an IPTA program, where the young poet was reciting his powerful composition “Jalta hai Punjab”—a passionate response to the horrors of Partition [7][2]. The poem, which began with “Jalta Hai Punjab Hamara Pyara, Jalta hai Bhagat Singh Ki Annkon Ka Taara” (Our beloved Punjab is burning, the star of Bhagat Singh’s eyes is burning), moved Raj Kapoor so profoundly that he immediately offered to purchase the rights for his directorial debut “Aag” (1948) [8].

However, the idealistic young poet, committed to his communist principles and wary of commercial cinema’s capitalist nature, firmly refused Kapoor’s offer. “I don’t write for money,” Shailendra declared. “There is nothing that might inspire me to write a song for your film. Why should I write then?” [2][9] This principled stance reflected his deep commitment to using poetry as a tool for social awakening rather than commercial entertainment.

Fate intervened when personal circumstances forced Shailendra to reconsider his position. With his wife pregnant and facing severe financial constraints, he approached Raj Kapoor’s office at Mahalaxmi with a humble request: “I need money. I need five hundred rupees. In return, assign me any work that you seem appropriate” [2][9]. This moment of vulnerability marked the beginning of one of Hindi cinema’s most successful creative partnerships.

The Golden Partnership: Raj Kapoor, Shankar-Jaikishan, and Shailendra

Kapoor, who was then working on his second directorial venture “Barsaat” (1949), needed lyrics for two songs after Hasrat Jaipuri had already written six [2]. For ₹500, Shailendra penned “Patli kamar hai” and “Barsaat mein humse mile tum,” compositions that not only became instant hits but established the foundation for a legendary collaboration [1][10].

The success of “Barsaat” cemented the creative alliance between Raj Kapoor, Shailendra, music directors Shankar-Jaikishan, and fellow lyricist Hasrat Jaipuri [10]. This team would go on to define Hindi cinema’s golden musical era, creating songs that transcended geographical and cultural boundaries. Raj Kapoor’s admiration for Shailendra was so profound that he fondly called him “Pushkin” after the Russian poet, and “Kaviraj” (poet-king)[2].

Vintage black and white photo of two men from the Indian film industry, potentially during the Raj Kapoor-Shailendra film collaboration era.

Their collaboration reached its pinnacle with “Awara” (1951), where Shailendra’s genius was on full display. When screenwriter Khwaja Ahmed Abbas narrated the film’s complex story, Shailendra instantaneously captured its essence in a single line: “Awara hoon, ya gardish mein hoon aasman ka taara hoon” (I am a vagabond, or am I in turmoil, a star of the sky) [4][11]. This remarkable ability to distill complex narratives into simple, evocative poetry left Abbas stunned and convinced Raj Kapoor of Shailendra’s cinematic genius.

The song “Awara Hoon” became more than just a film composition—it evolved into a cultural phenomenon that found appreciation across continents, particularly in the Soviet Union and China[1][6]. This international recognition established Shailendra as a lyricist whose words could transcend linguistic and cultural barriers.

Literary Style and Philosophy

Shailendra’s writing style was revolutionary in its deliberate simplicity and accessibility. Unlike many contemporary lyricists who favored ornate Urdu vocabulary and complex metaphors, Shailendra wrote in everyday Hindi (Hindustani) that ordinary people could understand and relate to [4][12]. This approach reflected his fundamental belief that poetry should serve the people rather than showcase literary sophistication.

His lyrics demonstrated what critics have called a “trademark writing style” that expressed complex emotions and philosophical thoughts in the simplest words [13]. Like the dohas of the 15th-century mystic poet Kabir, Shailendra’s compositions carried profound philosophical depths while remaining accessible to common listeners [13][11]. This parallel to Kabir was no coincidence—both poets shared a commitment to spiritual democracy and social justice.

Handwritten manuscript of lyrics attributed to lyricist Shailendra showcasing his artistic script and style.

The simplicity of Shailendra’s language masked sophisticated literary techniques and deep emotional intelligence. Songs like “Pyaar hua ikraar hua” from “Shree 420” (1955), “Kisi ki muskurahaton pe ho nisaar” from “Anari” (1959), and “Sajan re jhooth mat bolo” from “Teesri Kasam” (1966) exemplified his ability to create philosophical masterpieces using everyday vocabulary [13][14].

Major Collaborations and Memorable Compositions

While Shailendra’s association with Raj Kapoor and Shankar-Jaikishan produced his most famous works, his collaborations extended beyond this core team. His partnership with composer Salil Chowdhury yielded remarkable results, particularly in “Do Bigha Zamin” (1953) and the masterpiece “Madhumati” (1958) [15]. The latter film’s album is considered one of the finest in Hindi cinema history, featuring gems like “Suhana safar aur yeh mausam haseen.”

His work with S.D. Burman in “Guide” (1965) produced philosophical compositions like “Musafir jaaye ga kahan,” where he posed existential questions about life’s journey and meaning [13]. For Bimal Roy, he created memorable lyrics for “Bandini” (1963), including “O mere majhi,” which combined remarkable literary depth with popular appeal [16].

The song “Mera joota hai Japani” from “Shree 420” deserves special mention as it encapsulated the newly independent India’s complex relationship with globalization while asserting cultural identity. The lyrics—“Mera joota hai Japani, ye patloon Englishtani, sar pe laal topi Russi, phir bhi dil hai Hindustani” (My shoes are Japanese, these trousers English, the red cap on my head is Russian, yet my heart is Indian)—became an anthem of cultural pride [17][18].

Producer and the Tragic End

In 1961, Shailendra embarked on his most ambitious project as a producer with “Teesri Kasam” (1966), based on Phanishwar Nath Renu’s short story “Maare Gaye Gulfam” [1][15]. Directed by Basu Bhattacharya and starring Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman, the film represented Shailendra’s attempt to create meaningful cinema that aligned with his artistic and social values.

Despite winning the National Film Award for Best Feature Film and eventually being recognized as a cult classic, “Teesri Kasam” was a commercial disaster [1][15]. The film’s failure devastated Shailendra both financially and emotionally. The man who had brought joy to millions through his songs found himself overwhelmed by debt and betrayal by those he had trusted [11][19].

The financial strain, coupled with the emotional trauma of the film’s failure, led to severe health deterioration [1][11]. Shailendra increasingly turned to alcohol to cope with his depression and anxiety. His final composition, “Jeena yahan, marna yahan, iske siva jaana kahan” (To live here, to die here, where else can one go) for Raj Kapoor’s “Mera Naam Joker,” remained incomplete at his death[1][11].

Vintage photograph of five men from RK Films team, likely including lyricist Shailendra, showcasing a classic Bollywood film industry setting.

On December 14, 1966—ironically, Raj Kapoor’s 42nd birthday—Shailendra passed away at the young age of 43 [11][19]. His son Shaily Shailendra would later complete the unfinished song, which became one of Hindi cinema’s most poignant compositions about life’s inevitability.

Legacy and Impact

Shailendra’s influence on Hindi cinema extends far beyond his impressive discography. He fundamentally transformed how films communicated with audiences, proving that sophisticated artistry could coexist with mass appeal. His approach to lyricism inspired subsequent generations of writers, with luminaries like Gulzar and Javed Akhtar acknowledging his profound influence [1][11].

Gulzar has repeatedly stated that “Shailendra was the best lyricist produced by the Hindi film industry” [1]. Javed Akhtar has praised Shailendra’s work as literature rather than mere songwriting, describing him as a “public philosopher” who embedded correct values for Indian society within his compositions [4]. These assessments reflect the lasting impact of his artistic vision.

The international recognition of songs like “Awara Hoon” demonstrated Hindi cinema’s potential for global reach. The song’s popularity in the Soviet Union, China, and other countries proved that authentic artistic expression could transcend political and cultural boundaries [1][6]. In 2016, his composition “Mera Joota Hai Japani” was featured in the Hollywood film “Deadpool,” introducing his work to new international audiences[1].

Contemporary recognition of Shailendra’s contributions continues to grow. In 2016, a street in Mathura was named “Geetkar-Jankavi Shailendra Marg” in his honor [1]. Academic studies increasingly examine his work’s literary merit and social significance, recognizing him as a bridge between classical Indian poetry traditions and modern popular culture.

Conclusion

Shailendra’s life story embodies the transformative power of art to transcend social barriers and speak to universal human experiences. From his origins as a discriminated Downtrodden child to his position as Hindi cinema’s most beloved lyricist, his journey reflects both personal triumph and the democratic potential of popular culture.

His lasting legacy lies not just in the hundreds of songs that continue to move listeners decades after their creation, but in his demonstration that artistic excellence and social consciousness are not mutually exclusive. Through his simple yet profound words, Shailendra gave voice to the hopes, dreams, and struggles of ordinary people while elevating popular cinema to the realm of literature.

The man who once declared that he wanted to “arouse the people of India” with his poetry succeeded beyond his wildest dreams [3]. His songs remain integral to Indian cultural consciousness, serving as bridges between past and present, between the struggles of yesterday and the aspirations of today. In an industry often criticized for commercialism over content, Shailendra’s work stands as an enduring testament to the power of authentic artistic expression to move hearts and change minds.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shailendra_(lyricist)

- https://theprint.in/feature/shailendra-everymans-lyricist-who-turned-into-raj-kapoors-pushkin/724931/

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/mumbai-news/tracking-the-journey-of-a-cr-welder-who-became-hindi-cinema-s-literary-icon-101699185040666.html

- https://sangeetgalaxy.co.in/paper/shailendra-the-best-lyricist-in-hindi-cinema/

- https://theprint.in/theprint-profile/shailendra-the-leftist-poet-and-dalit-genius-whose-lyrics-define-beauty-of-simplicity/335262/

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/music/news/engineer-songsmith-revolutionary-shailendra-died-young-to-live-forever/articleshow/93904140.cms

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mWFxYBGXWYs

- https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/amritsar/recalling-peoples-poet-shailendra-in-raj-kapoors-centenary-year/

- https://www.news18.com/entertainment/bollywood/how-raj-kapoor-reacted-when-shailendra-died-on-filmmakers-42nd-birthday-7719319.html

- https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/art-and-culture/shailendra-raj-kapoors-pushkin-and-hindi-cinemas-poet-of-the-people

- https://www.boloji.com/articles/53395/kaviraj-shailendra-a-tribute–1

- https://www.swaraalap.com/the-luminaries/representation-of-common-man-in-shailendras-lyrics/

- https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/cafe/remembering-shailendra-perish-for-love-that-is-life

- https://learningandcreativity.com/silhouette/songs-of-shailendra/

- https://mavrix.in/2017/12/the-best-of-shailendra/

- https://kaykay46.wordpress.com/2023/08/31/remembering-shailendra-part-1/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YgFtgGt8pL0

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fy7P_Uu3alA

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGGP5B_rNBA

- https://www.forwardpress.in/2016/11/shaken-up-by-shailendra/

- https://www.dailyo.in/arts/shailendra-raj-kapoor-indian-cinema-hindi-films-barsaat-rk-films-14557

- https://open.spotify.com/track/7LpVrKyeiVKR9prdzIZFbE

- https://www.millenniumpost.in/entertainment/timeless-verses-of-shailendra-619549

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSt6CB9f9BY

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYkr-FeIvRI

- https://www.indiaforums.com/forum/music-corner/5336534/celebrating-the-centennial-of-a-beloved-hindi-lyricist-shailendra

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AdjVZ2XLPHs

- https://musicunrestricted.in/2023/08/30/shailendra/