The First War of Independence, 1857: A Comprehensive Analysis of India’s Great Uprising

The First War of Independence of 1857, also known as the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Sepoy Mutiny, or the Great Revolt, stands as one of the most significant chapters in India’s struggle against colonial rule. This massive uprising against the British East India Company marked a turning point in the subcontinent’s history, representing the first large-scale, coordinated resistance to foreign domination. While ultimately unsuccessful in achieving its immediate objectives, the revolt laid the foundation for future nationalist movements and fundamentally altered the nature of British rule in India.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Historical Context and Background

By 1857, the British East India Company had established its dominance over large parts of the Indian subcontinent through a century of conquest, expansion, and administrative control. The period between 1757 and 1857 witnessed the systematic dismantling of traditional Indian power structures, economic exploitation, and cultural interference that created widespread resentment among various sections of society. The accumulated grievances of rulers, peasants, soldiers, artisans, and religious leaders had reached a breaking point, creating conditions ripe for a mass uprising.[1][2][7][6]

Multifaceted Causes of the Revolt

Political Causes

The political foundations of the revolt were laid through aggressive British expansionist policies that systematically eroded Indian sovereignty. The Doctrine of Lapse, introduced by Lord Dalhousie, became a primary source of resentment among Indian rulers. This policy allowed the British to annex states if rulers died without direct male heirs, effectively denying the traditional practice of adoption. Major princely states including Satara, Jhansi, Nagpur, and Sambalpur fell victim to this policy, creating a powerful group of dispossessed rulers who harbored deep grievances against British rule.[1][2][8][9][10]

The annexation of Awadh in 1856 on grounds of “misgovernance” further intensified anti-British sentiment. This action displaced thousands of nobles, officials, and soldiers who had served the Nawab, adding to the pool of discontented elements. The British policy of subsidiary alliance also gradually reduced Indian rulers to mere puppets, stripping them of real authority while maintaining the facade of independence. [2][9][7]

Economic Exploitation

The economic causes of the revolt stemmed from the systematic drain of wealth from India to Britain and the destruction of traditional industries. The colonial administration implemented exploitative land revenue systems including the Permanent Settlement, Ryotwari, and Mahalwari systems that imposed heavy taxation on peasants. These policies led to widespread agricultural distress and the displacement of traditional landowners.[2][11][7]

British industrial policy deliberately suppressed Indian handicrafts and manufacturing to create markets for British goods. The once-thriving textile industry of Bengal, the metalwork of Deccan, and other traditional crafts were systematically destroyed, leaving millions of artisans unemployed. Discriminatory tariff policies further favored British imports while penalizing Indian exports, contributing to the economic devastation of the country.[7]

Social and Religious Grievances

The social and religious causes of the revolt were deeply intertwined with British attempts to reform Indian society according to Western values. While some reforms like the abolition of Sati and female infanticide had merit, the manner of their implementation and the underlying cultural insensitivity created widespread anxiety about religious and social identity.[12][13][14]

The introduction of Western education, railways, and telegraph systems was viewed with suspicion by traditionalists who saw these innovations as threats to established customs. The Religious Disabilities Act of 1850 changed Hindu property laws, allowing converts to Christianity to inherit property, which was perceived as an encouragement to religious conversion. The growth of Christian missionary activity and reports of forced conversions further inflamed religious sentiments.[13][15][14]

British racial attitudes and discriminatory practices created deep resentment among Indians who found themselves excluded from positions of authority in their own country. The policy of racial segregation in clubs, churches, and social gatherings reinforced the colonial hierarchy and wounded Indian pride.[11][13]

Military Discontent

The immediate military causes centered around the sepoys’ grievances regarding service conditions, pay, and religious sensibilities. The General Enlistment Act of 1856 required Bengal Army sepoys to serve overseas, violating caste taboos and religious beliefs. The disparity in treatment between European and Indian soldiers, including differences in pay, promotion prospects, and living conditions, created deep resentment within the ranks.[2][11]

The Enfield Cartridge Controversy

The immediate trigger for the revolt was the introduction of the new Enfield P53 rifle and its controversial cartridges. The cartridges were greased with a mixture of beef and pork fat to make them easier to load. Since the loading process required soldiers to bite off the cartridge end with their teeth, this violated the religious sensibilities of both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. For Hindus, contact with beef fat was religiously offensive, while for Muslims, pork fat was considered unclean (haram). [9][16][17][18]

Despite British attempts to address these concerns by suggesting alternative greasing methods using ghee or vegetable oil, the damage to trust had already been done. The cartridge issue became a symbol of British disregard for Indian religious beliefs and provided the spark that ignited the accumulated grievances of the sepoys.[16][17]

The Course of the Rebellion

Initial Outbreak and Spread

The first signs of discontent appeared at Berhampore on February 26, 1857, when sepoys of the 19th Native Infantry refused to participate in rifle practice. The situation escalated dramatically on March 29, 1857, at Barrackpore, where sepoy Mangal Pandey of the 34th Native Infantry attacked his British officers. Pandey’s act of defiance, though quickly suppressed, served as an inspiration for other sepoys and marked the beginning of organized resistance.[19][20][8]

The full-scale mutiny erupted at Meerut on May 10, 1857, when 85 sepoys of the 3rd Light Cavalry who had refused to use the new cartridges were court-martialed and imprisoned. Their comrades rose in rebellion, killed British officers, released the imprisoned sepoys, and marched to Delhi.[21][22][19]

Delhi: The Symbolic Center

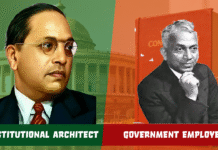

The rebels’ choice of Delhi as their destination was strategically significant. The city housed Bahadur Shah Zafar, the aged and powerless last Mughal emperor, whom the rebels proclaimed as their leader. This symbolic elevation of the Mughal emperor provided the revolt with a unifying figurehead and legitimized the uprising as a restoration of traditional Indian authority.[19][21][22][5]

Artistic portrait of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor during the First War of Independence in 1857.

The proclamation of Bahadur Shah as Emperor of India resonated across northern India, where the Mughal dynasty still commanded respect as the traditional symbol of Indian political unity. However, real power in Delhi lay with the court of soldiers led by General Bakht Khan, who arrived from Bareilly and established effective military control.[20][8][22][5]

Major Centers of Revolt and Leadership

The rebellion quickly spread across northern and central India, with major centers emerging in Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, Bareilly, and other strategic locations. Each center developed its own leadership and character while maintaining nominal allegiance to Bahadur Shah Zafar.[2][21][22]

The Etah District Uprising: Chetram Jatav and Ballu Mehtar

The Etah district in Uttar Pradesh witnessed one of the most significant examples of Downtrodden (Dalit) participation in the 1857 revolt through the heroic actions of Chetram Jatav and Ballu Mehtar. On May 26, 1857, these two brave freedom fighters launched their rebellion in the Soro region of Etah district, becoming driving forces behind the uprising in their locality. [1][2][3][4][5]

Chetram Jatav (1827-1857) was born on July 19, 1827, in Soro village of Etah district into a Jatav family. According to legend, his extraordinary physical strength and courage caught the attention of Maharaja Patiala, who witnessed Chetram carrying a lion on his back after killing it without any weapon. Impressed by this feat, the Maharaja invited him to join his army, where Chetram served with distinction.[2][3][5][6]

When the flames of the 1857 revolt spread to Etah district, both Chetram Jatav and Ballu Mehtar immediately joined the cause. They organized local resistance against British forces, working alongside other revolutionaries including Sadashiv Mehre and Chaturbhuj Vaishya. Their rebellion presented a formidable challenge to Phillips, the British officer of Etah district, demonstrating the effectiveness of their organized resistance.[4][1]

The courage of these Downtrodden (Dalit) freedom fighters is evident from their willingness to confront British military might despite lacking sophisticated weapons and resources. Their rebellion represented the grassroots nature of the 1857 uprising, showing how the revolt had penetrated to the village level and engaged people from all sections of society.[7][8][4]

The brutal end of their resistance exemplifies the savage British response to indigenous rebellion. Both Chetram Jatav and Ballu Mehtar were captured by British forces and executed in the most humiliating manner possible – they were tied to trees and shot dead on May 26, 1857. This method of execution was designed not just to kill but to terrorize local populations and deter future resistance.[5][8][1][7]

Lucknow witnessed fierce resistance under Begum Hazrat Mahal, who proclaimed her young son Birjis Qadr as the Nawab of Awadh. She was assisted by Maulvi Ahmadullah, a charismatic religious leader who gave the revolt a jihadi character and organized widespread civilian participation.[8][20]

Jaunpur emerged as another significant center of resistance under the leadership of Banke Chamar, whose story exemplifies the grassroots nature of the 1857 uprising and highlights the often-overlooked contributions of marginalized communities. Born on July 27, 1820, in Kuarpur village, Machhali Shahar, Jaunpur district, Banke Chamar became one of the most formidable local leaders of the rebellion.[1][2][3]

The extent of Banke Chamar’s effectiveness as a revolutionary leader can be measured by the British response to his activities. The colonial administration placed an unprecedented bounty of ₹50,000 on his head – a massive sum considering that at the time, two cows could be purchased for just six paisa. This reward amount reflected both the serious threat he posed to British authority and the significant impact of his resistance activities in the Jaunpur region.[3][4][1]

Banke Chamar’s leadership extended beyond individual heroism; he organized a network of 18 associates who conducted coordinated resistance activities against British forces. Their guerrilla tactics and intimate knowledge of the local terrain made them particularly effective in harassing British troops and disrupting colonial administration in the region. The British declared all of them as “baghis” (rebels), acknowledging their organized resistance.[2][4][1][3]

The end of Banke Chamar’s rebellion came through betrayal, a common fate for many resistance leaders of 1857. Ramashankar Tiwari, a retired British soldier turned informer, revealed their location to the authorities. When British forces arrived to capture the rebels, a fierce battle ensued in which Banke Chamar and his companions killed many British soldiers before being overwhelmed and captured. On December 18, 1857, Banke Chamar and his 18 associates were executed by hanging, making the ultimate sacrifice for their motherland. [4][1][2][3]

Kanpur became a crucial battleground under the leadership of Nana Saheb, the adopted son of the last Peshwa Baji Rao II. Nana Saheb declared himself Peshwa, acknowledged Bahadur Shah as emperor, and appointed himself as the emperor’s governor. His military commander Tantia Tope employed innovative guerrilla tactics that proved highly effective against British forces. [20][8][22]

Jhansi became synonymous with the heroic resistance of Rani Lakshmibai, who embodied the spirit of defiance against British rule. Her famous declaration, “Main apni Jhansi nahin doongi” (I shall not surrender my Jhansi), became a rallying cry for Indian resistance. After the fall of Jhansi, she joined Tantia Tope in a final stand at Gwalior, where she died fighting British forces in March 1858. [19][20][8]

Historical illustration showing Indian and British soldiers during the 1857 rebellion.

In Bihar, the revolt was led by Kunwar Singh, a 70-year-old zamindar from Jagdishpur who proved to be one of the most effective military leaders of the rebellion. Despite his advanced age, he successfully combined military and civilian resistance, making him particularly feared by the British.[20][8]

Uda Devi Pasi: The Legendary Sniper of Lucknow

Uda Devi Pasi (1830-1857) stands out as one of the most remarkable Downtrodden (Dalit) women warriors of the First War of Independence, earning recognition as a formidable sniper whose exploits became legendary among British forces. Born on June 30, 1830, in Ujariya village (now known as Gomti Nagar) in Lucknow district, she belonged to the Pasi community and was married to Makka Pasi, a wrestler and soldier in Begum Hazrat Mahal’s army. [9][10][11][12][13]

When the revolt erupted in Awadh, Uda Devi approached Begum Hazrat Mahal, the wife of the deposed Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, to enlist in the resistance movement. Recognizing her determination and capabilities, the Begum helped her establish a women’s battalion consisting largely of Downtrodden (Dalit) women who became known as “Veeranginas” (brave heroines). This women’s unit represented a unique aspect of the 1857 revolt – the organized participation of marginalized women in armed resistance against colonial rule.[10][12][13][9]

The turning point in Uda Devi’s life came when her husband Makka Pasi was martyred in the Battle of Chinhat. Devastated by grief but fueled by determination for revenge, she transformed her sorrow into a fierce resolve to avenge her husband’s death and defend her motherland.[11][12][13][9]

The Battle of Sikandar Bagh: A Sniper’s Last Stand

Uda Devi’s most famous action occurred during the Battle of Sikandar Bagh in November 1857, where her extraordinary marksmanship skills became the stuff of legend. As British forces under General Colin Campbell advanced to relieve the besieged British garrison at the Lucknow Residency, Uda Devi positioned herself strategically to inflict maximum damage on the enemy.[9][10][11]

After giving final instructions to her battalion, Uda Devi climbed a pipal tree in the Sikandar Bagh garden, armed with two heavy cavalry pistols and sufficient ammunition. From this elevated position, she began systematically picking off British soldiers as they advanced. Her accuracy was devastating – she reportedly killed between 32 to 36 British soldiers from her tree-top position.[12][13][10][11]

British officers initially could not locate the source of the deadly accurate fire that was decimating their ranks. The steep, downward trajectory of the bullet wounds puzzled them until they realized a hidden sniper was operating from an elevated position. W. Gordon-Alexander and other British commanders documented the unusual nature of the casualties, noting the precision and effectiveness of the shooting.[13][11]

When British forces finally identified her location and returned fire, Uda Devi was struck and fell from the tree. It was only after her death that the British soldiers discovered their formidable adversary was a woman. The discovery shocked the British forces – they had been outfought by a Downtrodden (Dalit) woman whose tactical acumen and marksmanship had inflicted significant casualties on their supposedly superior force.[10][11][12][13]

General Campbell himself was reportedly so impressed by her bravery and skill that he respectfully saluted her fallen body. This gesture of respect from an enemy commander speaks volumes about the impact Uda Devi had made through her courageous last stand. When her body was searched, soldiers found that one of her pistols was still loaded and her ammunition pouch was half full, indicating she could have continued fighting if not killed.[11][13]

Regional Downtrodden (Dalit) Resistance Networks

The revolt witnessed organized Downtrodden (Dalit)participation across various regions. In Azamgarh district’s Majhauwa village, four Chamars sacrificed their lives in the 1857 rebellion and are still worshipped at the shrine of “Shahid Baba” by local Downtrodden (Dalit)communities. This indicates that Downtrodden (Dalit) participation was not limited to individual heroics but involved community-level organization and sacrifice.[6]

Veera Pasi served as the security guard of Raja Beni Madhav Singh of Murar Mau in Rae Bareli and participated in the resistance activities in his region. The Pasi community’s involvement demonstrates how various Downtrodden (Dalit) castes contributed to the uprising across different princely states and regions.[5]

These examples illustrate that the 1857 revolt had significant grassroots participation from marginalized communities who saw the uprising as an opportunity to challenge both colonial rule and the existing social hierarchy. Their participation was motivated not just by anti-British sentiment but also by hopes for social transformation and the end of oppression.[7][6][5]

Unsung Heroes of the Marginalized Communities

The participation of Downtrodden (Dalits) in the First War of Independence has been historically under-documented, but recent scholarship has begun to uncover the significant contributions of marginalized communities to the 1857 uprising. Contemporary Downtrodden (Dalit) intellectuals and historians argue that the revolt would not have been possible without the active participation of Downtrodden (Dalit), who constituted a substantial portion of the population.[5][6][7]

Matadin Valmiki played a crucial catalytic role in the events leading to the revolt. Working as a cartridge manufacturer at Barrackpore, Matadin was involved in the production of the controversial Enfield cartridges that became the immediate trigger for the uprising. When sepoy Mangal Pandey refused to give him water due to caste considerations, Matadin’s angry retort about the contradiction between Pandey’s caste pride and his willingness to bite cartridges greased with cow and pig fat awakened both Hindu and Muslim soldiers to the religious implications of their service. Thus, Matadin Valmiki’s intervention became a crucial factor in raising consciousness about the cartridge controversy.[8][5][3]

In the Etah region of Uttar Pradesh, Chetram Jatav and Balluram Mehtar led their communities in armed resistance against British forces. Alongside other revolutionaries including Sadashiv Mehre and Chaturbhuj Vaishya, they organized attacks on British positions. However, lacking proper coordination and resources, their uprising was suppressed, and they were captured and executed by British forces.[5][3]

Regional Variations and Limitations

While the revolt achieved remarkable geographical spread, covering much of northern and central India, it failed to gain significant traction in certain regions. The presidency armies of Madras and Bombay remained largely loyal to the British, as did most of the princely states in Rajasthan, Punjab, and southern India. [2][23][24]

The revolt’s limited success in certain areas can be attributed to various factors including effective British diplomacy, regional loyalties, and the self-interest of local rulers who saw opportunities to gain British favor. The Sikh community in Punjab, recently defeated by the British in the Anglo-Sikh Wars, remained largely neutral or even supportive of British rule. [23][24]

British Response and Suppression

The British response to the revolt was swift and brutal, characterized by a combination of military efficiency and savage reprisals. The campaign to suppress the rebellion was conducted in three main phases: the desperate struggles during the summer of 1857 around Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow; the operations around Lucknow in winter 1857-58 under Colin Campbell; and the final “mopping up” campaigns led by Hugh Rose in early 1858.[10][4]

Illustration of the 1857 Indian Rebellion showing combat between sepoys and British soldiers.

The British employed a strategy of “divide and rule,” exploiting existing divisions among Indian communities and rewarding those who remained loyal. The brutality of the suppression included mass executions, the infamous practice of strapping rebels to cannon mouths and firing them, and the systematic destruction of villages suspected of supporting the revolt.[10][4][25][26]

Reasons for Failure

The failure of the 1857 revolt can be attributed to several critical factors that prevented it from achieving its objectives. The most significant weakness was the lack of unified leadership and coordination among the various centers of revolt. While Bahadur Shah Zafar served as a symbolic figurehead, there was no central command structure to coordinate strategy and resources. [27][28][23]

The revolt suffered from limited geographical spread, failing to engage the entire subcontinent. The absence of support from key regions like Madras, Bombay presidencies, and most princely states significantly weakened the rebellion’s impact. Many Indian rulers chose to support the British, calculating that their interests lay with the established power. [23][24][27]

Technological and military disadvantages played a crucial role in the revolt’s failure. The rebels lacked modern weapons, artillery, and military expertise compared to the well-equipped and professionally trained British forces. The British advantage in communication through telegraph systems allowed them to coordinate their response effectively while the rebels struggled with poor communications. [28][27]

The revolt also faced resource constraints and financial limitations. Unlike the British, who had access to significant financial resources and could pay their troops regularly, the rebel forces often struggled with supply shortages and irregular payments. [27][28]

Social and class divisions within Indian society prevented the formation of a truly united front against British rule. The educated middle class, merchants, and many traditional elites either remained neutral or actively supported the British, calculating that their interests were better served by collaboration rather than confrontation. [28][27]

Portrait of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor and a key figure in the First War of Independence in 1857.

Consequences and Historical Significance

Immediate Consequences

The most immediate and significant consequence of the 1857 revolt was the transfer of power from the East India Company to the British Crown. The Government of India Act of 1858 formally ended Company rule and established direct Crown control over India. Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of November 1, 1858, announced the new arrangement and promised respect for Indian customs, religious freedom, and equality under law.[4][25][26]

The Indian Army underwent complete reorganization based on the principle of “divide and counterpoise”. The proportion of European to Indian troops was increased, artillery units were largely transferred to European control, and recruitment policies favored “martial races” considered more loyal to British rule. The Army Amalgamation Scheme of 1861 transferred Company troops to Crown service and implemented regular rotation of European officers.[25][4]

Administrative and Policy Changes

The revolt led to significant changes in British administrative policies and attitudes toward Indian society. The aggressive annexation policies were abandoned, and the British began cultivating the support of princely states through guarantees of non-interference in internal affairs. This marked the beginning of the “divide and rule” policy that would characterize British administration for the remainder of the colonial period. [4][25][26]

Historical illustration of a battle scene during the First War of Independence, 1857, showing British soldiers and Indian rebels in combat.

However, the British response also became more conservative and autocratic. The aspirations of educated Indians for greater participation in governance were largely ignored, leading to frustration among the emerging middle class. This exclusion would prove to be a crucial factor in the development of organized nationalist movements in the following decades. [4][26]

⚔️ Rebel vs Loyalist Communities in 1857

| Aspect | Rebel Communities / States | Loyalist Communities / States |

|---|---|---|

| Key Leaders / States | Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II, Nana Sahib (Kanpur), Banke Chamar (Jaunpur), Begum Hazrat Mahal (Awadh), Kunwar Singh (Bihar), Chetram Jatav (Etah), various taluqdars & zamindars | Nizam of Hyderabad, Scindia of Gwalior, Nawab of Rampur, Dogra rulers of Kashmir, Sikh chiefs (Patiala, Nabha, Jind), Mysore Wodeyars |

| Regions of Strength | Awadh, Delhi, Kanpur, Jhansi, Jaunpur, Etah, Bihar, Bundelkhand, parts of Rajasthan & Central India | Punjab, Bengal, Deccan, South India, Kashmir, Nepal frontier, Bombay & Madras Presidencies |

| Communities Involved | Sepoys of Bengal Army, peasants, artisans, Gujars, Chamars, Rajputs, Pathans (some clans), Rohillas, Marathas, dispossessed zamindars | Sikhs, Jats, Gorkhas (Nepalese troops), loyal Pathan clans, Bengali zamindars, merchants (Baniyas, Marwaris), South Indian sepoys |

| Causes of Position | – Resentment over greased cartridges (religious insult) – Annexations (Doctrine of Lapse, e.g., Jhansi, Awadh) – Heavy taxation & land reforms – Decline of traditional elites | – Political survival & rivalry with rebels – Dependence on British protection – Economic interest in stability – Past conflicts with Mughals/Marathas (Sikhs, Gorkhas) |

| Military Role | Attacked British garrisons, seized Delhi, fought pitched battles (Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, Etah, Jaunpur, Lucknow, Gwalior) | Provided troops, supplies, and safe bases; Punjab & Gorkha forces crucial in retaking Delhi & Lucknow |

| Outcome | Defeated by mid‑1858; leaders killed, Betrayed, captured, or exiled; massive reprisals and land confiscations | Rewarded with titles, land, and political recognition; many princely states retained autonomy under Crown rule |

✅ Key Takeaway: The rebels represented dispossessed elites, sepoys, and agrarian communities hurt by British policies, while the loyalists were largely princely states, frontier allies, and trading classes who saw stability and advantage in siding with the British. This balance of rebellion vs loyalty explains why the uprising, though widespread, could not become a pan‑Indian war of independence.

Long-term Impact on Indian Nationalism

Despite its immediate failure, the 1857 revolt had profound long-term significance for the development of Indian nationalism. The uprising demonstrated the possibility of unified resistance against British rule and provided inspiration for future generations of freedom fighters. The stories of heroism, sacrifice, and martyrdom associated with leaders like Rani Lakshmibai, Tantia Tope, and Kunwar Singh became part of Indian nationalist mythology. [5][26][6]

The revolt also highlighted the importance of unity across religious and regional divisions. The fact that Hindus and Muslims fought together under the symbolic leadership of the Mughal emperor while respecting Hindu traditions demonstrated the possibility of secular nationalism that would later influence the independence movement. [5]

Historical Interpretation and Debate

The 1857 revolt has been subject to varying interpretations by different historians and political movements. British colonial historians typically characterized it as a “mutiny” or “rebellion,” emphasizing its military aspects and downplaying its popular support. Post-independence Indian historians have generally viewed it as the “First War of Independence,” emphasizing its nationalist character and popular participation.[3][5][6]

Modern scholarship recognizes the complexity of the event, acknowledging both its limitations and its significance. While the revolt lacked the organized character of later nationalist movements, it represented a crucial transitional moment in Indian resistance to colonial rule. The uprising combined traditional forms of resistance with emerging modern political consciousness, making it a bridge between pre-modern and modern forms of anti-colonial struggle. [26][6]

📊 Communities & States Loyal to the Britisher’s (1857)

| Category | Examples | Region | Reason for Loyalty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Princely States | Nizam of Hyderabad, Mysore Wodeyars, Dogra rulers of Kashmir, Scindia of Gwalior, Nawab of Rampur, Sikh states (Patiala, Nabha, Jind) | Deccan, South India, Punjab, Central India | Political survival, rivalry with rebels, dependence on British protection |

| Sikh Chiefs | Patiala, Nabha, Jind, Kapurthala | Punjab | Past conflicts with Mughals & Marathas, saw British as stabilizing force |

| Gorkhas (Nepal) | Troops sent by Jung Bahadur Rana | Nepal & British India frontier | Alliance with British, military tradition, reward expectations |

| Pathans (some clans) | Certain Pashtun tribes | North-West Frontier | Local rivalries, British frontier policy alliances |

| Bengali Zamindars | Landed elites, moneylenders, merchants (Baniyas, Marwaris) | Bengal & Eastern India | Economic interests, fear of instability, reliance on British law/order |

| Presidency Armies | Madras & Bombay sepoys | South & West India | Less exposure to greased cartridge issue, distance from North Indian discontent |

| Merchants & Traders | Baniyas, Marwaris, urban trading classes | Across India | Wanted stability for trade, feared rebel plunder |

✅ Key Insight: The loyalty of Sikhs, Gorkhas, princely states, and Bengal’s neutrality gave the British the manpower, resources, and safe bases to regroup and crush the rebellion. Without these allies, the revolt might have spread much further.

Reclaiming Hidden Narratives

Legacy and Historical Recognition

The contributions of Chetram Jatav, Ballu Mehtar, and Uda Devi Pasi have gained increasing recognition in contemporary India as part of efforts to acknowledge the full spectrum of participation in the independence struggle. The Bahujan Samaj Party has adopted these figures as icons of Downtrodden (Dalit) heroism, organizing commemorative events and building memorials to preserve their memory.[3][2][12]

In Lucknow, the BSP government named the land behind Samta Mulak Chowk as “Shaheed Chetram Jatav Park” to honor his sacrifice. A statue of Uda Devi Pasi stands at Sikandar Bagh in Lucknow, depicting her with a rifle and a determined expression, serving as a permanent reminder of her courage.[6][12][5][13][10]

Every year on November 16, members of the Pasi community and other admirers gather at Sikandar Bagh to commemorate Uda Devi’s martyrdom. These observances help preserve the memory of her sacrifice and inspire contemporary generations with examples of courage and patriotism from their own communities.[12][11]

The stories of these Downtrodden (Dalit) freedom fighters serve multiple important functions in contemporary Indian society. They provide a more complete and accurate historical record of the 1857 uprising, challenge dominant narratives that marginalized the contributions of oppressed communities, and offer sources of pride and inspiration to Downtrodden (Dalit) communities today. Their inclusion in the historical narrative demonstrates that the First War of Independence was truly a people’s movement that transcended caste boundaries and involved extraordinary acts of heroism from individuals across all sections of society.[2][3][4][12]

The brutal executions of Chetram Jatav and Ballu Mehtar, and the heroic death of Uda Devi Pasi, exemplify the price paid by ordinary Indians from marginalized communities in the struggle for freedom. Their sacrifices remind us that the independence movement began with countless unnamed heroes who chose death over subjugation, laying the foundation for eventual freedom through their blood and courage.[8][5][13][11][12]

The Politics of Historical Memory

The historical marginalization of Downtrodden (Dalit)contributions to the 1857 revolt reflects broader patterns of exclusion in mainstream historical narratives. As Downtrodden (Dalit) intellectual movements have gained strength, there has been a conscious effort to recover and highlight these suppressed stories. The emergence of alternative historical accounts challenges the conventional narrative that portrayed the revolt primarily as an dominant-caste and elite phenomenon.[6][7]

Contemporary Downtrodden (Dalit) literature and oral traditions preserve memories of numerous heroes like Jhalkari Bai, Avantibai, Pannadhai, Udadevi, and Mahaviri Devi, who fought alongside or in support of major rebellion leaders. These accounts suggest that women from marginalized communities also played significant roles in the uprising, both as combatants and as supporters of the resistance movement.[5]

The recognition of figures like Banke Chamar and other Downtrodden (Dalit) freedom fighters serves multiple purposes: it provides a more complete and accurate picture of the 1857 uprising, gives due credit to marginalized communities for their sacrifices, and offers inspiration and pride to contemporary Downtrodden (Dalit) communities. In 2015, the government acknowledged Matadin Valmiki’s contribution by naming a crossing in Meerut as “Shaheed Matadin Chowk”. [7][8][6]

The stories of Banke Chamar, Chetram Jatav, Ballu Mehtar and other Downtrodden (Dalit) revolutionaries demonstrate that the First War of Independence was truly a people’s uprising that transcended caste boundaries, even as the colonial state and post-independence historiography often obscured these contributions. Their inclusion in the narrative of 1857 not only corrects historical injustices but also enriches our understanding of the complex social dynamics that fueled India’s first major anti-colonial uprising. [6][7][5] These grassroots leaders like Banke Chamar, operating at the village and district level, formed the backbone of the resistance movement, proving that the struggle for independence involved not just prominent rulers and nobles, but ordinary people from all sections of society who were willing to sacrifice everything for their motherland’s freedom. [1][2][3]

📊 Downtrodden (Dalit) Participation in 1857

| Name / Community | Caste / Group | Region of Action | Role in 1857 | Legacy / Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamar Community | Dalit caste | Kanpur, Jhansi, Bundelkhand | Joined rebel sepoys, fought in village uprisings, provided logistical support | Colonial records branded them as “criminal tribes,” erasing their sacrifices |

| Jhalkaribai | Kori (Dalit) | Jhansi (Bundelkhand) | Close aide of Rani Lakshmibai; disguised herself as the queen to mislead British forces during the siege | Celebrated as a Dalit Virangana; statues, folk songs, and Dalit movements honor her courage |

| Uda Devi | Pasi (Dalit) | Lucknow (Awadh) | Fought under Begum Hazrat Mahal; climbed a tree and shot down British soldiers before being killed | Remembered as a fearless Dalit woman warrior; honored in Pasi community traditions |

| Avanti Bai (Ramgarh) | Often linked with Gond but celebrated in Dalit narratives | Central India (Madhya Pradesh) | Led armed resistance against British troops after her husband’s death | Symbol of women’s resistance; invoked in Dalit and Adivasi histories |

| Pasi Community | Dalit caste | Awadh region | Formed guerrilla bands, supported Begum Hazrat Mahal’s forces | Oral traditions preserve their role; marginalized in mainstream history |

| Kori Community | Dalit caste | Jhansi region | Supported Jhalkaribai and local resistance | Folk memory and Dalit literature highlight their bravery |

| Other Dalit groups (sweepers, leather-workers, agricultural laborers) | Various Dalit castes | North India (esp. Awadh, Bundelkhand) | Carried messages, supplied food, fought in local skirmishes | Contributions largely erased from official histories |

✅ Key Insight: Dalit participation was both individual (Jhalkaribai, Uda Devi) and collective (Pasis, Chamars, Koris). Their sacrifices were immense, but colonial and nationalist historiography marginalized them. Modern Dalit scholarship is reclaiming these voices.

Conclusion

The First War of Independence of 1857 represents a watershed moment in Indian history, marking the end of the East India Company’s rule and the beginning of direct Crown administration. While the revolt failed to achieve its immediate objective of ending British rule, its impact on the trajectory of Indian nationalism and colonial policy was profound and lasting.[4][26][6]

The uprising demonstrated both the potential for unified resistance against colonial rule and the challenges facing such movements in the context of 19th-century India. The complex interplay of political, economic, social, and religious grievances that fueled the revolt would continue to influence Indian nationalism throughout the colonial period.[5][6]

The legacy of 1857 lives on in Indian collective memory as a symbol of courage, sacrifice, and the refusal to accept foreign domination. The revolt’s heroes, particularly figures like Rani Lakshmibai, Tantia Tope, and Bahadur Shah Zafar, remain important symbols of resistance and patriotism. Their stories continue to inspire and remind us that the struggle for independence began long before the organized movements of the 20th century.[6][5]

The First War of Independence thus stands not merely as a failed rebellion but as the opening chapter of India’s long journey toward freedom, laying the groundwork for the eventual success of the independence movement nearly a century later. Its lessons about unity, organization, and the importance of popular support would prove invaluable for future generations of freedom fighters who would ultimately achieve what the heroes of 1857 had dreamed of but could not accomplish.

- https://newmancollege.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/1-POLITICAL-CAUSES-1857-revolt.pdf

- https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/revolt-of-1857/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Rebellion_of_1857

- https://edukemy.com/blog/consequences-significance-of-the-1857-revolt-upsc-modern-history-notes/

- https://amritkaal.nic.in/blogdetail.htm?50

- https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2502289.pdf

- https://www.nextias.com/blog/causes-of-revolt-of-1857/

- https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/list-of-important-leaders-associated-with-the-revolt-of-1857/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_the_Indian_Rebellion_of_1857

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Indian-Rebellion-of-1857

- https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/revolt-of-1857/

- https://studynlearn.com/the-great-uprising-of-1857

- https://www.doubtnut.com/pcmb-questions/66927

- https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/revolt-of-1857-social-causes

- https://newmancollege.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2-SOCIO-RELIGIOUS-CAUSES-1857-revolt.pdf

- https://www.royal-irish.com/artefacts/cartridges-and-indian-mutiny

- https://testbook.com/question-answer/rumors-about-the-cartridges-of-which-of-the-follow–61c0c1c351817e36836c02ca

- https://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/amit/books/palmer-1966-mutiny-outbreak-at.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_Indian_Rebellion_of_1857

- https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/important-leaders-of-the-revolt-of-1857/

- https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/decisive-events-indian-mutiny

- https://www.nextias.com/blog/revolt-of-1857/

- https://rajras.in/ras/mains/paper-1/rajasthan-history/revolt-of-1857-in-rajasthan/

- https://pwonlyias.com/udaan/1857-revolt/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/social-science/consequences-of-the-revolt-of-1857/

- https://www.irjweb.com/THE CROWNS RESPONSE REFORMS IN BRITISH INDIA AFTER THE 1857 REVOLT.pdf

- https://prepp.in/news/e-492-causes-of-failure-of-revolt-of-1857-modern-indian-history-notes

- https://www.doubtnut.com/pcmb-questions/66933

- https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/list-of-important-leaders-associated-with-the-revolt-of-1857-1466160043-1

- https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/why-did-indian-mutiny-happen

- https://testbook.com/ias-preparation/list-of-important-leaders-associated-with-the-revolt-of-1857

- https://www.vedantu.com/general-knowledge/list-of-important-leaders-associated-with-the-revolt-of-1857

- https://www.drishtiias.com/to-the-points/paper1/revolt-of-1857

- https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/the-revolt-of-1857-causes-nature-importance-and-outcomes-1444211359-1

- https://www.vedantu.com/question-answer/causes-of-the-failure-of-1857-revolt-class-12-social-science-cbse-5fe9ebc1a729973d3fabb63f

- https://theiashub.com/free-resources/modern-history/government-of-india-act-1858-colonial-policy-shift

- https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/9ikwko/after_the_indian_rebellion_of_1857_over_the_use/

- http://indianculture.gov.in/digital-district-repository/district-repository/participation-mohomed-saydul-bukht-first-war-0

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Banke_Chamar

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banke_Chamar

- https://bharatvoice.in/history/dalit-contribution-to-the-first-war-of-independence.html

- https://www.instagram.com/reel/C4qp6losTVD/?hl=en

- https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol12-issue1/1201199202.pdf

- https://iisjoa.org/sites/default/files/iisjoa/July 2024/16th Paper.pdf

- https://www.pratilipi.in/2008/06/the-role-of-dalits-in-the-1857-revolt-badri-narayan/

- https://www.worldhindunews.com/dalit-contributions-to-the-first-war-of-independence-in-1857/

- https://www.rediff.com/news/report/revolt/20051110.htm

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/4419578

- https://www.altnews.in/photo-of-kaibarta-eastern-bengal-shared-as-dalit-freedom-fighter-banke-chamar-and-udaiya-chamar/

- https://swarajyamag.com/politics/dalit-heroism-against-british-rule-is-well-known-yet-the-neo-dalits-think-otherwise

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cg6UvLk3ZqI

- https://en.themooknayak.com/bahujan-nayak/the-forgotten-bahujan-warriors-of-indias-first-war-of-independence-rescuing-the-braveheart-stories-of-the-indian-mutiny

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Rebellion_of_1857

- https://indianculture.gov.in/node/2820643

- https://en.bharatpedia.org/wiki/Chetram_Jatav

- https://chakrafoundation.org/chetram-jatav/

- https://www.academia.edu/124082367/National_Movement_and_Dalit_Struggle_A_Sociological_Perspective

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chetram_Jatav

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Chetram_Jatav

- https://www.rediff.com/news/report/revolt/20051110.htm

- https://www.rediff.com/news/2005/nov/10revolt.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uda_Devi

- https://iasbaba.com/2022/11/uda-devi/

- https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V2ISSUE12/IJRPR2071.pdf

- https://www.ambedkaritetoday.com/2019/01/uda-devi-a-dalit-women-freedom-fighter.html

- http://www.amarchitrakatha.com/history_details/uda-devi-a-true-veerangini/

- http://14.139.58.200/ojs/index.php/shss/article/download/1446/1453/2288

- https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol12-issue1/1201199202.pdf

- https://www.sriramsias.com/upsc-daily-current-affairs/uda-devi-pasi-the-dalit-warrior-who-stood-her-ground-against-the-british/

- https://www.gktoday.in/question/where-was-uda-devi-pasi-the-dalit-woman-freedom-fighter-of-the-1857-in-510646

- https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/unsung-heroes-detail.htm?11011

- https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/uda-devi-and-maharaja-bijli-pasi

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/4419578