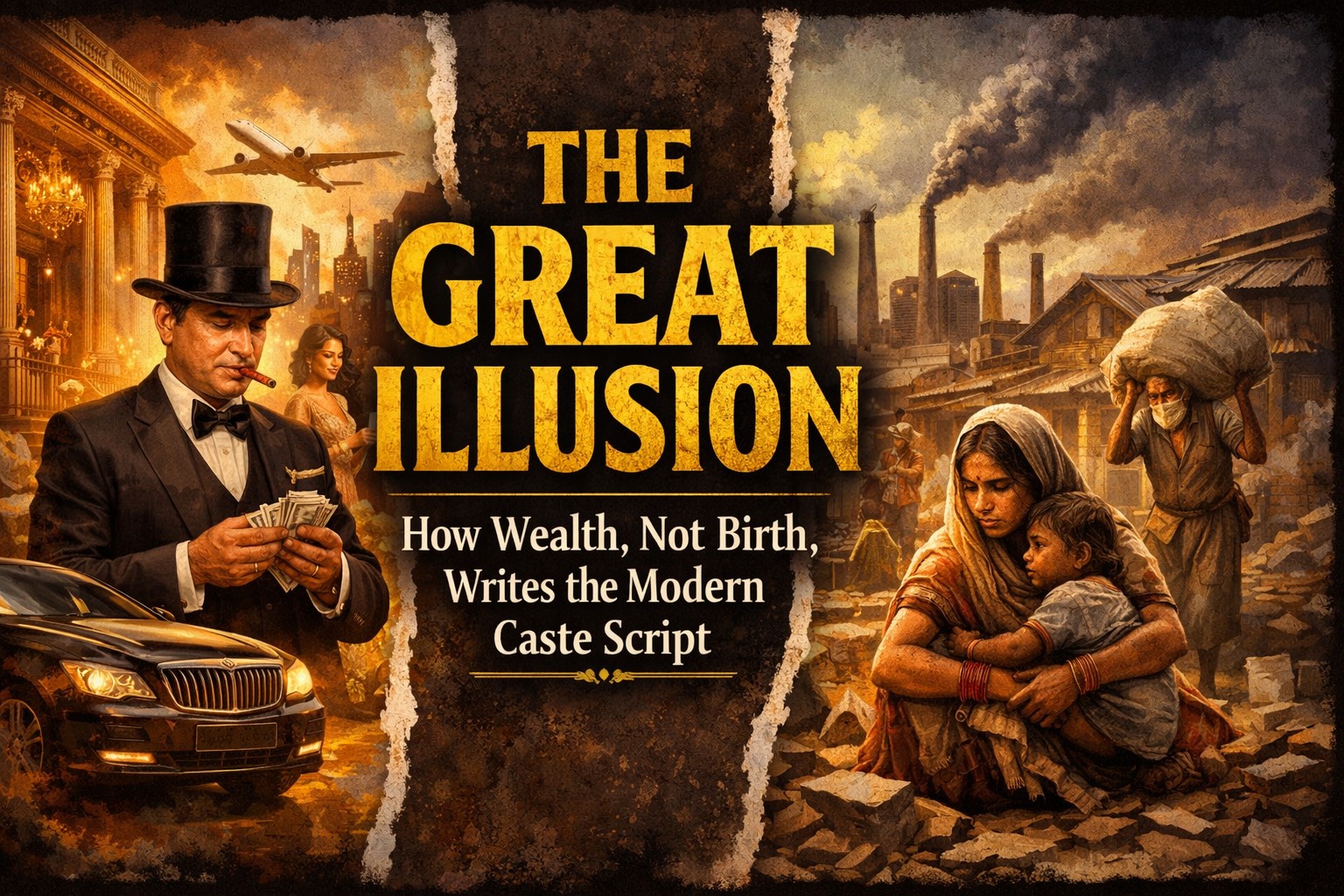

The Great Illusion: How Wealth, Not Birth, Writes the Modern Caste Script

For centuries, the Indian social fabric has been defined by the rigid hierarchy of caste—a system that assigns status, profession, and social value by birth. The terms “upper caste” and “lower caste” are woven into our collective consciousness, language, and politics, presented as an immutable reality. But what if this entire edifice, in its modern manifestation, is not a temple of inherent superiority or inferiority, but a bank? What if, upon stripping away the layers of ritual and tradition, we find that the true currency of caste today is not purity or profession, but cold, hard economic prosperity?

The uncomfortable truth is that without the scaffolding of wealth and status, the labels of “upper” and “lower” caste lose their power, revealing an economic hierarchy masquerading as a sacred one.

Historically, caste and occupation were intertwined. The system dictated that social and ritual status (the “upper” caste) was separate from, and often disdainful of, economic activities like commerce or manual labour. Yet, in today’s world, this script has flipped. The “value” of a caste tag is now almost entirely underwritten by the economic prosperity of the community or the individual bearing it. A wealthy, influential industrialist from a historically marginalized community commands a societal respect that often bypasses caste prejudice. Conversely, a impoverished Brahmin priest, while perhaps retaining ritual reverence, frequently faces the same social and economic marginalization—lack of opportunity, limited access to elite networks, and diminished societal voice—as any other poor citizen.

The performance of so-called “upper-caste” status is increasingly a performance of economic capital. It is sustained by the ability to live in certain neighborhoods, attend prestigious schools, access cultural capital, and wield political influence—all of which require significant wealth. The gatekeepers of “tradition” and “purity” are often those who have the financial means to maintain the facade, from grand temple donations to ostentatious ritual ceremonies. Meanwhile, the stigma of “lower caste” is compounded, and often primarily defined, by economic deprivation—landlessness, lack of assets, and generational poverty that limits access to education and healthcare.

This is not to deny the very real, visceral, and violent discrimination based on caste identity that persists. Caste-based prejudice is a grim reality. However, it operates within and is amplified by an economic framework. The discrimination often serves to preserve economic hierarchy. Restricting social mobility, marriage pools, and network access is a method of maintaining a monopoly on resources and opportunities. The “upper caste” label becomes a tool for protecting accumulated wealth, while the “lower caste” stigma is used to justify and perpetuate economic exclusion.

Look at the urban landscape: in corporate boardrooms, high-end apartments, and elite social clubs, caste identities often recede into the background, blurred by the common language of luxury, education, and global exposure. Here, a person’s worth is assessed by their net worth, their designation, their alma mater. The caste surname might be noted, but it is the economic and social capital that dictates inclusion. Conversely, in a village or an urban slum, where poverty is the great equalizer, caste distinctions may remain sharper precisely because there is little else—no wealth, no divergent status—to differentiate groups. The struggle is for basic resources, and caste becomes a battleground for claiming those scarce resources.

In essence, the modern caste structure is a proxy for class. The ancient code of varna has been largely overwritten by the modern algorithm of economic status. Wealth provides the support system—the lawyers to fight discrimination cases, the media influence to shape narratives, the political donations to buy clout, and the social insulation from the harshest realities of prejudice—that allows the “upper-caste” identity to retain its perceived value.

To argue this is not to reduce the complex trauma of casteism to mere economics. It is to expose its primary contemporary engine. Dismantling the pernicious myth of inherent superiority requires us to see the system for what it has largely become: an elaborate socio-economic filter, where birth is used to justify the consolidation of wealth and the maintenance of privilege. Recognizing that without the backing of prosperity, the emperor of caste has no clothes is the first step toward a more honest conversation—one that moves beyond ritual hierarchy to address the foundational inequalities of wealth and opportunity that truly dictate who is “up” and who is “down” in today’s world.