Understanding Writs: A Comprehensive Guide for Law Students and Citizens

The concept of writs represents one of the most fundamental and powerful mechanisms in India’s constitutional framework for protecting individual rights and ensuring governmental accountability. As judicial instruments borrowed from English common law and adapted to India’s unique constitutional context, writs serve as the primary means through which citizens can seek immediate and effective relief when their fundamental rights are violated or when public authorities exceed their legal mandate. This comprehensive examination explores the intricate legal framework of writs, their historical development, practical applications, and their crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance between state power and individual liberty in the world’s largest democracy.

The Supreme Court of India, the highest judicial authority that issues writs under the Constitution jusscriptumlaw

Historical Foundation and Constitutional Genesis

The origin of writs in Indian jurisprudence can be traced back to medieval England, where they emerged as royal commands issued under the prerogative of the Crown to ensure justice was administered fairly across the realm. These prerogative writs gradually evolved into essential safeguards for individual liberties and became integral to the English legal system. The colonial administration introduced this concept to India through the Regulating Act of 1773, which established the first Supreme Court in Calcutta in 1774, followed by similar courts in Madras (1801) and Bombay (1823). These presidency courts inherited the power to issue writs, creating the foundation for what would eventually become a cornerstone of independent India’s judicial system.

The framers of the Indian Constitution, recognizing the immense value of these legal instruments in protecting individual rights, deliberately incorporated writ jurisdiction into the constitutional framework. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s characterization of Article 32 as the “heart and soul” of the Constitution underscores the central importance placed on these remedies in the constitutional scheme. The Constituent Assembly debates reveal a deep understanding among the framers that mere declaration of fundamental rights would be meaningless without effective mechanisms for their enforcement.

K.M. Munshi, a prominent member of the Constituent Assembly, emphasized that the exercise of writ jurisdiction would serve as a crucial check against violations of citizens’ rights and protect them from arbitrary state action through judicial scrutiny. He particularly highlighted how the power to issue habeas corpus would restrain unlawful detention and protect personal freedom. Similarly, Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar stressed that writ jurisdiction would provide an effective remedy against executive wrongdoing and enable judicial discretion when citizens’ rights faced potential infringement.

Constitutional Framework: Articles 32 and 226

The Constitution of India establishes a dual system of writ jurisdiction through two pivotal articles that empower different levels of the judiciary to issue these extraordinary remedies. This bifurcated approach ensures both accessibility at the regional level and ultimate recourse at the national level, creating a comprehensive protective framework for citizens’ rights.

Article 32: The Supreme Court’s Writ Jurisdiction

Article 32, often described as the “right to constitutional remedies,” establishes the Supreme Court as the ultimate guardian of fundamental rights. This provision grants Indian citizens the fundamental right to directly approach the apex court when their constitutional rights are violated, making it both a substantive right and a procedural mechanism for enforcement. The Article specifically empowers the Supreme Court to issue directions, orders, or writs including habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, certiorari, and quo warranto for the enforcement of fundamental rights.

The significance of Article 32 extends beyond its remedial function – it represents a fundamental departure from the Westminster model of parliamentary supremacy by establishing constitutional supremacy and judicial review. The provision ensures that fundamental rights are not merely aspirational statements but enforceable legal entitlements backed by the full authority of the highest court in the land.

Key characteristics of Article 32 include:

- Mandatory jurisdiction: The Supreme Court cannot refuse to exercise its writ jurisdiction when fundamental rights are violated

- Direct access: Citizens can approach the Supreme Court directly without exhausting other remedies

- Pan-India reach: The Court’s orders have effect throughout the territory of India

- Limited scope: Jurisdiction is restricted to enforcement of fundamental rights under Part III of the Constitution

Article 226: High Courts’ Writ Jurisdiction

Article 226 empowers High Courts with a broader writ jurisdiction that extends beyond fundamental rights to encompass any legal right or legitimate expectation. This provision grants High Courts discretionary power to issue writs, orders, or directions to any person or authority within their territorial jurisdiction, including government entities, for the enforcement of fundamental rights or “any other purpose”.

The scope of Article 226 is significantly wider than Article 32, as it allows High Courts to address violations of legal rights that may not necessarily be fundamental rights. This broader mandate enables High Courts to serve as the first line of judicial defense against administrative excesses and legal violations at the regional level.

Key features of Article 226 include:

- Discretionary jurisdiction: High Courts may choose whether to exercise their writ powers

- Broader scope: Covers fundamental rights, legal rights, and statutory entitlements

- Territorial limitation: Jurisdiction limited to the court’s territorial boundaries

- Alternative remedy consideration: Courts generally require exhaustion of alternative remedies before entertaining writ petitions

Comprehensive comparison between Article 32 and Article 226 writ jurisdiction in India

The Five Types of Writs: Detailed Analysis

The Indian Constitution recognizes five specific types of writs that serve distinct purposes in the judicial system. Each writ addresses particular legal scenarios and provides targeted remedies for different forms of governmental excess or rights violations.

Habeas Corpus: The Great Writ of Liberty

The writ of habeas corpus, meaning “to have the body,” stands as perhaps the most fundamental protection against arbitrary detention and unlawful imprisonment. This ancient writ compels authorities holding a person in custody to produce that individual before the court and justify the legality of their detention. If the court finds the detention unlawful, it can order the immediate release of the detained person.

Essential elements of habeas corpus include:

- Scope of protection: Guards against both state and private detention

- Immediacy: Provides swift relief in cases of unlawful imprisonment

- No formal requirements: Can be filed through letters or informal applications, as established in Sunil Batra vs. Delhi Administration (1979)

- Who can file: The detained person, family members, or even strangers acting in public interest

Limitations on habeas corpus:

- Cannot be issued when detention is lawful and within proper authority

- Not available when proceedings are for contempt of legislature or court

- Ineffective when detention is ordered by a competent court within jurisdiction

- Cannot be used when detention is outside the court’s territorial limits

The landmark case of Sunil Batra vs. Delhi Administration demonstrated the flexibility of this writ when the Supreme Court treated a letter from a stranger as a habeas corpus petition, emphasizing that the protection of personal liberty transcends procedural formalities.

Mandamus: The Command to Act

Mandamus, meaning “we command,” is a judicial order directing public authorities to perform their legal duties that they have failed or refused to execute. This writ serves as a powerful tool to compel government action and ensure that public bodies fulfill their statutory obligations to citizens.

Key applications of mandamus:

- Public duty enforcement: Compels performance of mandatory statutory duties

- Administrative accountability: Ensures government bodies act within their legal mandate

- Service delivery: Forces authorities to provide services or benefits legally owed to citizens

- Decision-making: Compels authorities to make decisions they are legally required to make

Conditions for issuing mandamus:

- Existence of a clear legal duty on the respondent authority

- Failure or refusal to perform that duty

- Petitioner must have a legal right to the performance of the duty

- No adequate alternative remedy available

- The duty must be mandatory, not discretionary

Limitations on mandamus:

- Cannot be issued against private individuals unless they perform public functions

- Not available to enforce contractual obligations

- Cannot compel discretionary decisions

- Not issued against constitutional authorities like the President or Governors in their official capacity

The case of Municipal Council, Ratlam vs. Shri Vardhichand & Ors. (1980) exemplifies mandamus in action, where the court compelled the municipality to remove public nuisances and perform its statutory duties to maintain public health.

Prohibition: Preventing Jurisdictional Excess

The writ of prohibition, meaning “to forbid,” is a preventive remedy that restrains lower courts or tribunals from exceeding their jurisdiction or acting without proper authority. Unlike mandamus, which commands action, prohibition specifically orders inaction and prevents the continuation of proceedings that exceed jurisdictional boundaries.

Functions of prohibition:

- Jurisdictional control: Prevents lower courts from exceeding their authority

- Procedural safeguards: Ensures adherence to natural justice principles

- Hierarchical order: Maintains proper judicial hierarchy and authority limits

- Preventive relief: Acts before jurisdictional excess causes irreparable harm

Grounds for issuing prohibition:

- Excess of jurisdiction by the lower court or tribunal

- Absence of jurisdiction over the subject matter

- Violation of principles of natural justice

- Acting in breach of statutory provisions governing jurisdiction

Scope limitations:

- Only applicable to judicial and quasi-judicial authorities

- Cannot be issued against purely administrative bodies

- Not available against legislative bodies or private entities

Certiorari: Correcting Legal Errors

Certiorari, meaning “to be certified” or “to be informed,” serves both preventive and corrective functions by allowing superior courts to review and quash decisions of lower courts or tribunals that suffer from jurisdictional errors or violations of natural justice. This writ can transfer pending cases to higher courts or nullify improper orders already passed.

Dual nature of certiorari:

- Corrective function: Quashes erroneous orders already passed

- Preventive function: Transfers cases before improper decisions are made

- Review mechanism: Enables scrutiny of lower court decisions for legal errors

- Rights protection: Safeguards against administrative excess and judicial error

Grounds for certiorari:

- Lack of jurisdiction in the deciding authority

- Excess of jurisdiction beyond legal limits

- Error of law apparent on the face of the record

- Violation of principles of natural justice

- Procedural irregularities affecting the decision

Evolution of scope: Originally limited to judicial and quasi-judicial bodies, the Supreme Court in 1991 expanded certiorari’s scope to include administrative authorities when their decisions affect individual rights.

Limitations:

- Cannot be issued against legislative bodies

- Not available against private individuals or entities

- Cannot correct mere errors of fact, only errors of law

Quo Warranto: Challenging Unauthorized Office Holding

Quo warranto, meaning “by what authority” or “by what warrant,” serves as a public law remedy to challenge the right of a person to hold a public office. This writ ensures that public offices are occupied only by persons legally entitled to hold them, thereby maintaining the integrity of public administration.

Purpose and scope:

- Office legitimacy: Ensures only qualified persons hold public office

- Public interest protection: Prevents usurpation of governmental positions

- Legal qualification verification: Confirms compliance with appointment requirements

- Democratic accountability: Maintains proper functioning of public institutions

Conditions for quo warranto:

- The office must be public in nature

- Created by statute or constitutional provision

- The office must be substantive, not merely honorary or ministerial

- The person must be claiming or exercising the office illegally

Who can file: Unlike other writs, quo warranto can be filed by any interested person, not just those directly affected. This reflects the public interest nature of ensuring legitimate office-holding.

Limitations:

- Cannot be applied to ministerial or private offices

- Not available against de facto officers performing duties legitimately

- Must be filed within reasonable time of the illegal assumption of office

Procedural Framework for Filing Writ Petitions

The process of filing writ petitions involves several crucial steps that require careful attention to legal and procedural requirements. Understanding this framework is essential for both legal practitioners and citizens seeking to access constitutional remedies.

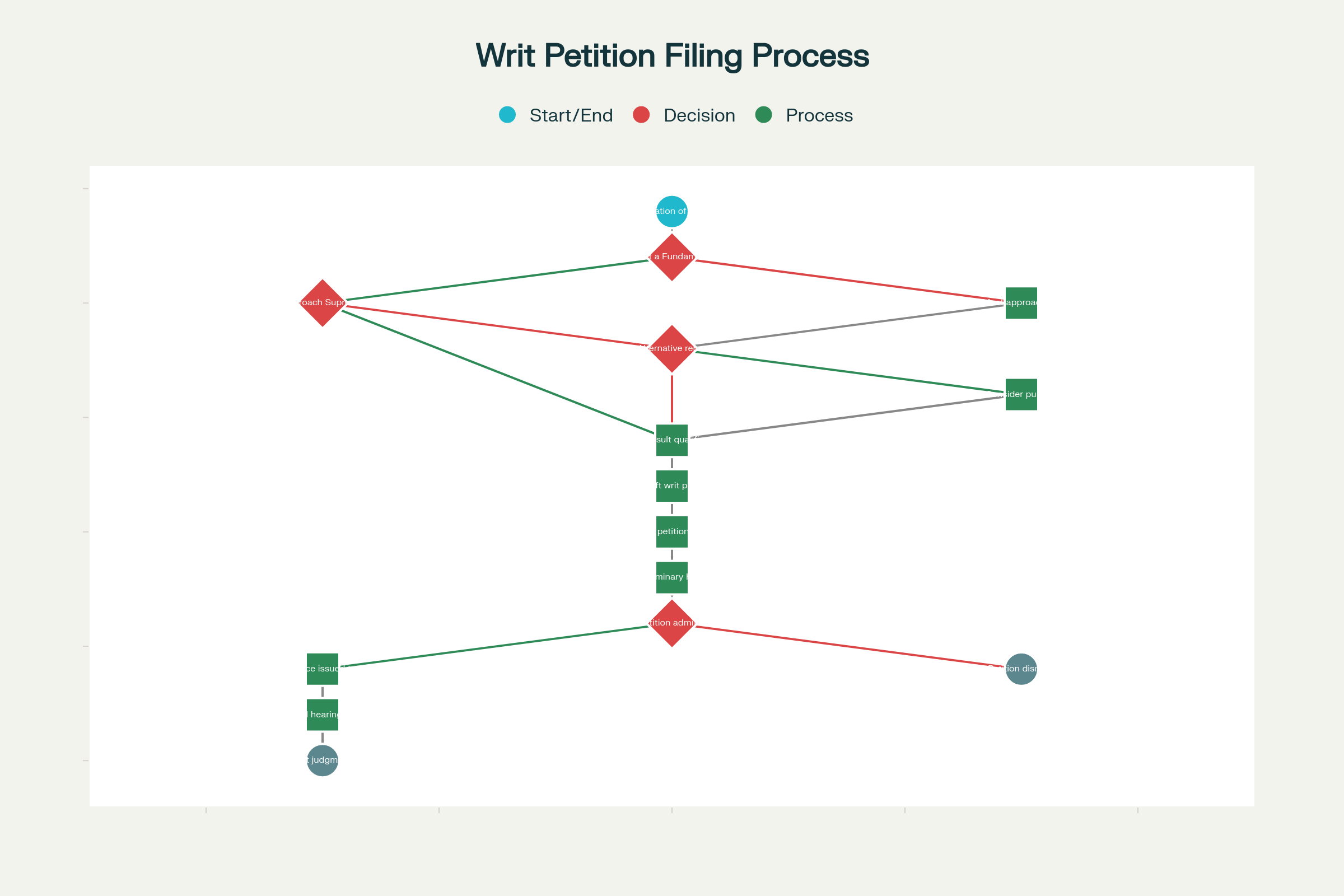

Step-by-step flowchart for filing a writ petition in Indian courts

Initial Assessment and Preparation

Before initiating writ proceedings, petitioners must conduct a thorough assessment of their legal situation. This involves:

Rights violation analysis: Clearly identifying which specific fundamental or legal rights have been violated and the exact nature of the violation. The petition must demonstrate a direct causal link between the respondent’s action or inaction and the harm suffered.

Jurisdictional determination: Deciding whether to approach the Supreme Court under Article 32 or the appropriate High Court under Article 226. This decision depends on factors such as the nature of rights violated, geographical considerations, and strategic legal advantages.

Alternative remedy evaluation: Assessing whether adequate alternative remedies exist and whether they should be pursued before filing the writ petition. While the availability of alternative remedies doesn’t automatically bar writ jurisdiction, courts generally expect petitioners to exhaust other available legal avenues unless exceptional circumstances exist.

Documentation gathering: Collecting all relevant documents, correspondence, orders, notifications, and evidence that support the petition. This includes proof of identity, residence, and any prior attempts to seek redress through normal channels.

Drafting the Writ Petition

The drafting stage represents the most critical aspect of writ proceedings, as a well-crafted petition significantly increases the chances of judicial consideration and ultimate success.

Essential components of a writ petition:

Title and jurisdiction: Clearly stating the court’s name, the constitutional provision invoked (Article 32 or 226), and the specific type of writ sought.

Party identification: Providing complete details of all petitioners and respondents, including their official designations, addresses, and the basis for their inclusion in the proceedings.

Jurisdictional basis: Explaining why the particular court has jurisdiction to entertain the petition and the legal grounds supporting this claim.

Statement of facts: Presenting a chronological narrative of all relevant events, with specific dates, documents, and actions that led to the rights violation. This section must be precise, complete, and supported by documentary evidence.

Legal grounds: Articulating the specific constitutional provisions, statutory duties, or legal principles that have been violated. This requires citing relevant case law, constitutional articles, and statutory provisions that support the petitioner’s position.

Relief sought: Clearly specifying the exact nature of relief requested from the court, including any interim measures needed to prevent further harm.

Supporting documents: Attaching all relevant annexures, numbered sequentially and referenced in the petition text.

Common Drafting Pitfalls to Avoid

Legal practitioners and petitioners must be aware of frequent mistakes that can undermine writ petitions:

Factual deficiencies: Vague allegations without specific dates, details, or supporting evidence weaken the petition’s credibility. Courts require precise facts to assess the validity of claims and the appropriate relief.

Jurisdictional errors: Approaching the wrong court or failing to establish proper jurisdictional basis can result in summary dismissal. Petitioners must carefully analyze whether their case falls within the chosen court’s territorial and subject matter jurisdiction.

Inadequate legal grounds: Failing to cite relevant constitutional provisions, statutes, or case law that support the petition’s claims. The legal framework must be clearly articulated and properly applied to the specific facts.

Improper party identification: Naming incorrect respondents or omitting necessary parties can render the petition defective. All authorities or individuals responsible for the rights violation must be properly identified and included.

Relief ambiguity: Seeking vague or legally impossible relief undermines the petition’s effectiveness. The prayer clause must be specific, legally sustainable, and directly related to the violation alleged.alc

Time delay issues: Filing petitions after unreasonable delays can invite dismissal on grounds of laches. While no specific limitation period applies to writ petitions, courts expect reasonable promptness in seeking relief.

Filing and Initial Proceedings

Once the petition is properly drafted and documented, the filing process involves several procedural steps:

Registry submission: Filing the petition with the appropriate number of copies at the court’s registry, along with prescribed court fees. Different courts may have varying requirements for the number of copies and fee structure.

Initial scrutiny: Court registries conduct preliminary examination to ensure compliance with basic procedural requirements. Defects in formatting, documentation, or fee payment can result in rejection at this stage.

Preliminary hearing: If the petition passes initial scrutiny, the court conducts a preliminary hearing to determine maintainability and prima facie merit. This hearing decides whether the petition raises substantial questions worthy of detailed consideration.

Notice issuance: Upon admission, the court issues notices to all respondents, requiring them to file replies within specified time frames. This formally brings all parties into the proceedings and initiates the adversarial process.

Final hearing: After receiving respondents’ replies, the court schedules final hearings where both parties present detailed arguments. The court may ask questions, seek clarifications, or request additional information during these proceedings.

Limitations and Conditions on Writ Jurisdiction

While writ jurisdiction represents a powerful tool for rights enforcement, it operates within certain legal and practical constraints that petitioners must understand and navigate carefully.

The Alternative Remedy Doctrine

One of the most significant limitations on writ jurisdiction involves the availability of alternative legal remedies. Courts generally expect petitioners to exhaust other available legal avenues before seeking extraordinary writ relief, though this principle isn’t absolute.

General rule: When adequate alternative remedies exist, courts typically decline to exercise writ jurisdiction. This encourages the use of specialized forums and prevents the overburdening of superior courts with matters that can be resolved through normal legal channels.

Exceptions to the rule: Courts recognize several circumstances where writ jurisdiction remains available despite alternative remedies:

- Fundamental rights violations: When constitutional rights are at stake

- Natural justice violations: Where fair procedure has been denied

- Jurisdictional questions: When the authority lacks power to act

- Constitutional challenges: When the validity of laws or rules is questioned

- Wholly inadequate remedies: When alternative forums cannot provide effective relief

Judicial discretion: The assessment of remedy adequacy involves judicial discretion based on the specific circumstances of each case. Courts consider factors such as the nature of rights involved, urgency of relief needed, and effectiveness of alternative forums.

Locus Standi Requirements

Traditional approach: Historically, only persons directly affected by rights violations could file writ petitions. This narrow interpretation limited access to justice and prevented broader public interest challenges to governmental action.

Liberal evolution: The Supreme Court has progressively liberalized standing requirements, particularly through the development of Public Interest Litigation (PIL). This evolution recognizes that certain rights violations affect society broadly and require intervention even by unaffected individuals.

Current framework: Modern jurisprudence permits writ petitions by:

- Directly affected individuals or entities

- Representatives of affected persons who cannot approach courts themselves

- Public-spirited citizens acting in genuine public interest

- Organizations and associations representing affected groups

Time Limitations and Delay

While no specific limitation period governs writ petitions, courts consistently emphasize the importance of reasonable promptness in seeking relief.

Doctrine of laches: Courts can dismiss petitions filed after unreasonable delays, even if no formal limitation period has expired. The rationale involves preventing stale claims and ensuring that public authorities can plan and act with some certainty.

Factors considered: In assessing delay, courts examine:

- The nature of the rights violated and urgency of relief needed

- Reasons for delay and whether they’re satisfactory

- Prejudice caused to respondents by delayed filing

- Changed circumstances that might affect the appropriateness of relief

- Public interest considerations

Exceptions for continuing violations: When rights violations are ongoing rather than one-time events, the limitation consideration may be relaxed. Continuing violations refresh the cause of action and justify delayed filing.

Jurisdictional Constraints

Territorial limitations: High Courts can generally exercise writ jurisdiction only within their territorial boundaries, though exceptions exist when the cause of action arises within their jurisdiction.

Subject matter restrictions: Article 32 limits Supreme Court writ jurisdiction to fundamental rights enforcement, while Article 226 permits broader coverage including legal and statutory rights.

Authority limitations: Writs can typically be issued only against public authorities or private entities exercising public functions. Pure private law disputes generally fall outside writ jurisdiction unless they involve broader public law implications.

Landmark Cases and Judicial Evolution

The development of writ jurisprudence in India has been shaped by several landmark Supreme Court decisions that have clarified principles, expanded scope, and refined procedures.

Foundational Cases

A.K. Gopalan vs. State of Madras (1950): This early case involving communist leader A.K. Gopalan’s detention under the Preventive Detention Act established important principles regarding the scope of Article 21 and the relationship between different fundamental rights. While the narrow interpretation adopted in this case was later overruled, it provided an initial framework for writ jurisprudence.

Maneka Gandhi vs. Union of India (1978): This transformative decision fundamentally altered the understanding of fundamental rights by establishing the “golden triangle” concept linking Articles 14, 19, and 21. The case overruled the restrictive approach in A.K. Gopalan and established that any law depriving personal liberty must satisfy the requirements of all three articles, not just Article 21.

Rights Expansion Cases

Fertilizer Corporation Kamgar Union vs. Union of India (1980): The Supreme Court held that the jurisdiction conferred by Article 32 forms an integral part of the Constitution’s basic structure. This decision elevated writ jurisdiction to constitutional bedrock status, making it immune from amendment that would destroy its essential character.

Sunil Batra vs. Delhi Administration (1979): This case demonstrated the flexibility of habeas corpus by accepting informal letters as writ petitions. The decision emphasized that constitutional remedies should be accessible to all citizens regardless of their ability to follow formal legal procedures.

Public Interest Litigation Development

The evolution of PIL through writ jurisdiction has democratized access to justice and enabled broader challenges to governmental action affecting society at large. Cases like Municipal Council, Ratlam vs. Shri Vardhichand (1980) showed how writ jurisdiction could address systemic public problems affecting entire communities.

Contemporary Challenges and Future Directions

Modern writ practice faces several challenges that require careful judicial and legislative attention to maintain effectiveness while preventing abuse.

Case Load Management

The increasing volume of writ petitions places significant strain on judicial resources. Courts must balance accessibility with efficiency, ensuring that genuine cases receive timely attention while preventing frivolous litigation from clogging the system.

Procedural Reforms

Ongoing efforts to streamline writ procedures through technological integration, standardized forms, and clearer guidelines aim to improve efficiency and accessibility. Electronic filing systems and digital case management represent important modernization steps.

Substantive Law Evolution

The expanding scope of fundamental rights through judicial interpretation creates new avenues for writ jurisdiction while raising questions about appropriate judicial limits. Courts must balance rights protection with respect for separation of powers and democratic governance.

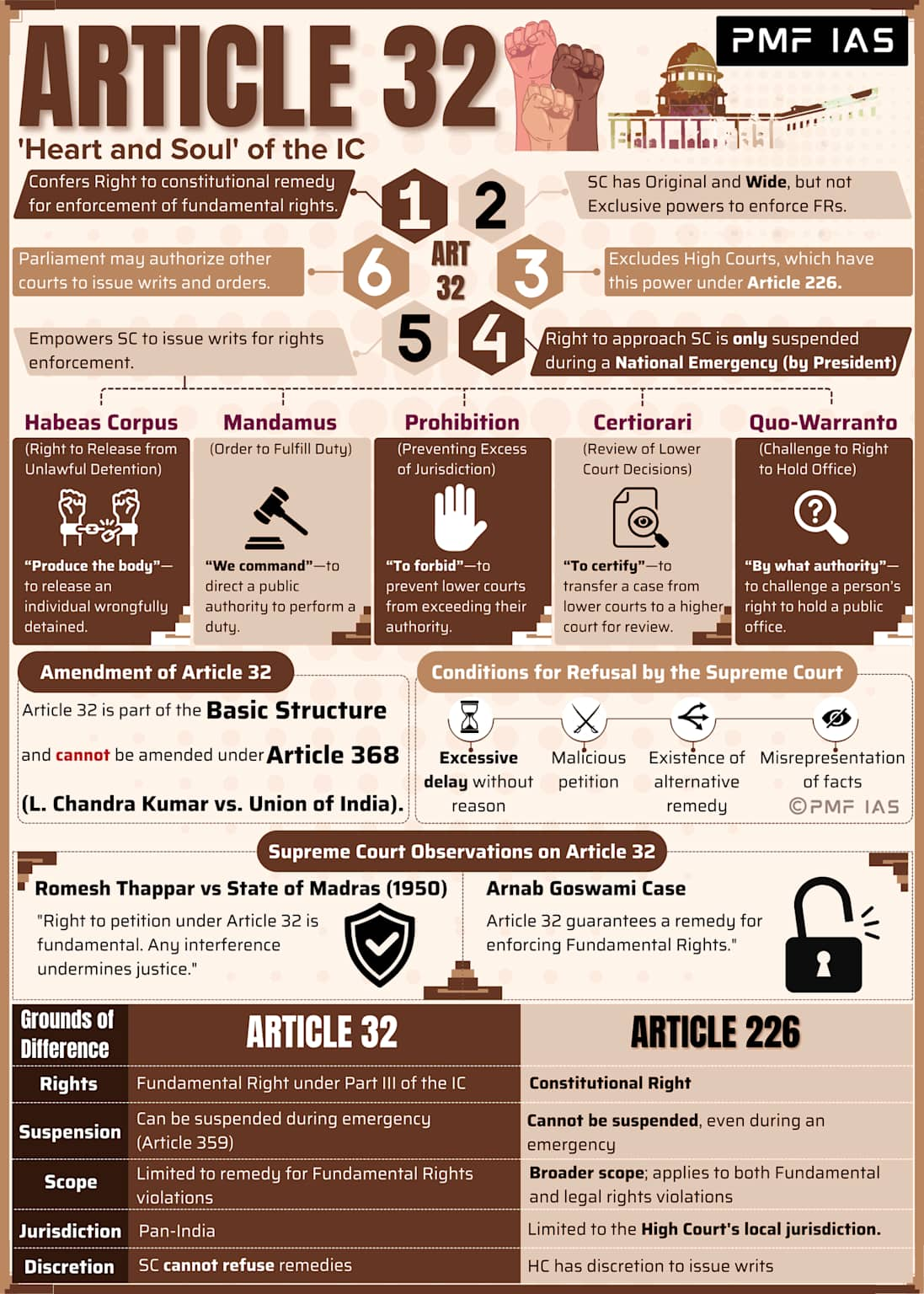

Infographic explaining Article 32 of the Indian Constitution and the five writs issued by the Supreme Court for enforcement of fundamental rights pmfias

Practical Guidance for Legal Practitioners

Strategic Considerations

Successful writ practice requires careful strategic planning that goes beyond technical legal requirements:

Forum selection: Choosing between Supreme Court and High Court jurisdiction requires weighing factors such as:

- Urgency of relief needed

- Complexity of legal issues involved

- Resource availability and costs

- Likelihood of success in different forums

- Appeal prospects and further litigation strategy

Timing considerations: The timing of writ petition filing can significantly impact success prospects. Practitioners must balance the need for prompt action with adequate preparation time and strategic considerations.

Relief crafting: The specific relief sought must be carefully tailored to address the actual harm while being practically enforceable. Overly broad or vague prayers can undermine petition effectiveness.

Client Counseling and Expectations

Realistic assessment: Practitioners must provide clients with honest assessments of their case prospects, including potential costs, time frames, and alternative options. Writ jurisdiction, while powerful, isn’t guaranteed to provide relief in every case.

Alternative strategies: Clients should understand available alternatives to writ proceedings, including statutory appeals, departmental remedies, and negotiated settlements. Sometimes non-litigation approaches may prove more effective and efficient.

Compliance preparation: Successful writ petitioners must be prepared to comply with court orders and participate constructively in implementation processes. Court orders often require ongoing cooperation and monitoring.

Conclusion: The Continuing Relevance of Writ Jurisdiction

The writ jurisdiction established under Articles 32 and 226 of the Indian Constitution represents one of the most significant achievements in the protection of individual rights and the maintenance of constitutional governance. These extraordinary remedies serve as vital safeguards against governmental excess and ensure that constitutional promises remain living realities rather than mere aspirational statements. The evolution of writ jurisprudence from its English origins through colonial adaptation to its current robust form in independent India demonstrates the adaptability and enduring relevance of these legal instruments.

For law students, understanding writs provides essential insights into the practical operation of constitutional law and the mechanisms through which abstract rights become enforceable legal entitlements. The study of writ jurisdiction illuminates fundamental concepts of judicial review, separation of powers, and the balance between individual liberty and state authority that lie at the heart of constitutional democracy.

For ordinary citizens, awareness of writ remedies empowers informed participation in democratic governance and provides accessible means for challenging governmental action that exceeds legal boundaries. The democratization of writ jurisdiction through PIL and relaxed standing requirements ensures that these powerful remedies remain available to all segments of society, regardless of economic or social status.

The future of writ jurisdiction in India will likely involve continued evolution to address emerging challenges while maintaining core protective functions. Technological integration, procedural streamlining, and substantive law development will shape how these ancient remedies adapt to modern governance challenges. However, the fundamental principle underlying writ jurisdiction – that governmental power must be exercised within legal limits and subject to judicial oversight – remains as relevant today as it was when these provisions were first incorporated into the Constitution.

The success of India’s constitutional democracy depends, in significant measure, on the continued vitality and accessibility of writ jurisdiction. These remedies represent the practical implementation of the rule of law and ensure that the Constitution remains a living document capable of protecting individual rights and maintaining governmental accountability in an ever-changing political and social landscape. As India continues its democratic journey, the writs will undoubtedly remain essential tools for ensuring that constitutional promises translate into constitutional realities for all citizens.

Through careful study, thoughtful application, and continued judicial development, writ jurisdiction will continue serving as a cornerstone of Indian constitutionalism, protecting individual liberty while enabling effective governance within the framework of law. The challenge for future generations of lawyers, judges, and citizens lies in preserving and strengthening these vital constitutional protections while adapting them to meet the evolving needs of a dynamic democracy.