The main contents of the article are as follows:

- Introduction: Overview of the Panwari case and its significance.

- Historical context: Background of caste dynamics and the 1990 incident.

- The violence: Details of the clash, police response, and aftermath.

- Legal journey: Investigation, charges, delays, and verdict.

- Socio-political impact: Political reactions, media coverage, and societal changes.

- Conclusion: Reflections on justice, reconciliation, and lessons learned.

The Agra Panwari Case: A 35-Year Quest for Justice in India’s Battle Against Caste Violence

1 Introduction: A Landmark Verdict After Three Decades

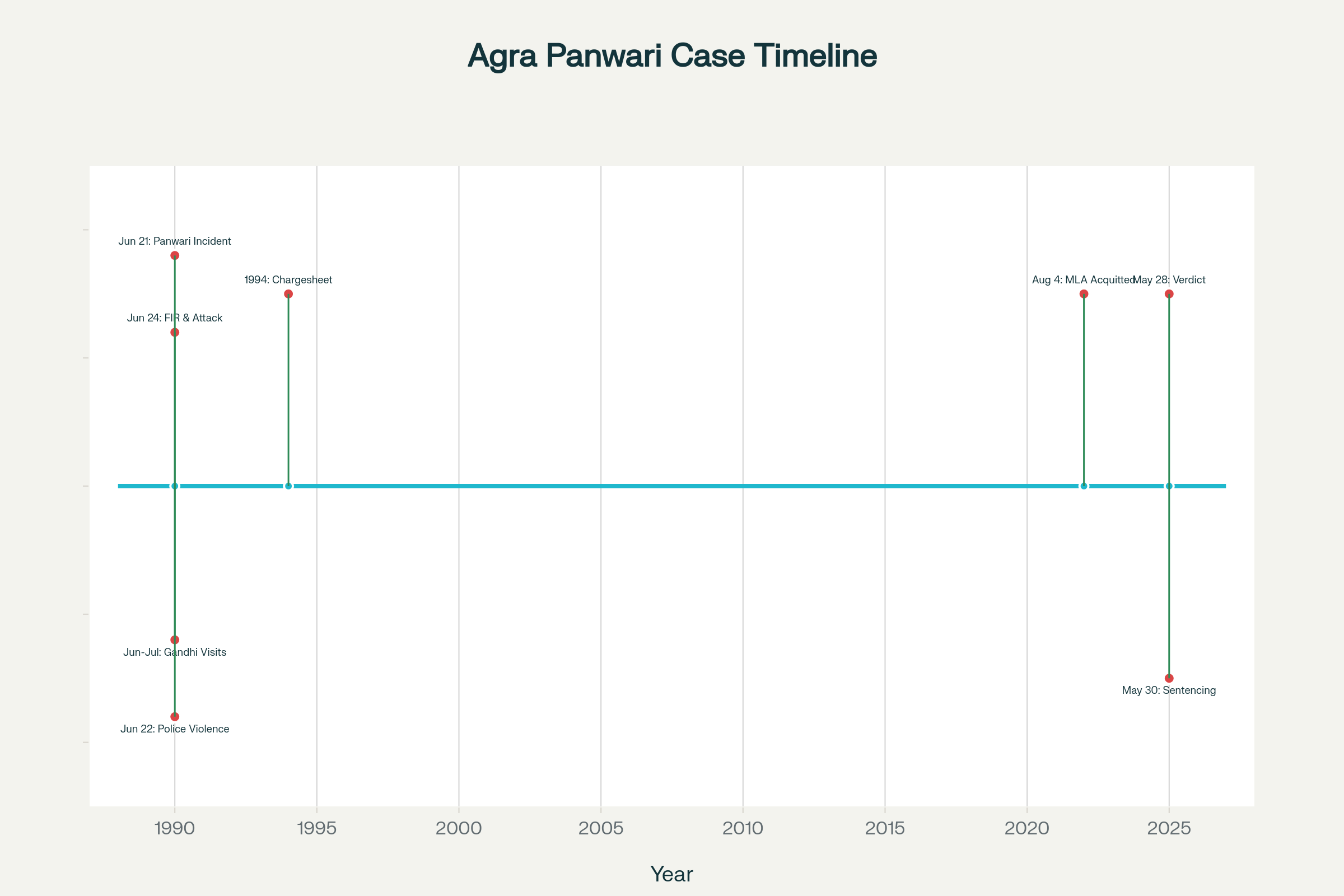

The Agra Panwari case stands as one of India’s most prolonged and politically significant caste-based violence cases in post-independence history. After 34 years of legal battles, procedural delays, and societal tensions, a special SC/ST court in Agra finally convicted 36 individuals on May 28, 2025, for their role in the violent 1990 caste clash that erupted over a Downtrodden (Dalit) wedding procession. This verdict, delivered more than three decades after the incident, highlights both the persistent challenges of India’s judicial system in addressing caste-based violence and the enduring struggle for dignity by marginalized communities. The case exposed the deep-rooted caste prejudices in rural Uttar Pradesh and became a watershed moment in Downtrodden (Dalit) political mobilization in northern India.

The Panwari case transcended its local origins to become a national symbol of resistance against caste oppression, drawing interventions from top political leaders, influencing state politics, and sparking nationwide debates about the implementation of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. This article examines the historical context, legal journey, political ramifications, and social impact of this landmark case that kept a community waiting for justice for over three decades.

2 Historical Context: Caste Dynamics and the Prelude to Violence

To understand the significance of the Panwari case, one must appreciate the caste demographics of western Uttar Pradesh in the late 20th century. The region has historically witnessed complex power dynamics between dominant land-owning communities (particularly Jats) and Downtrodden (Dalit) communities (primarily Jatavs/Chamars), who though numerically significant, faced systemic discrimination and economic exploitation .

The immediate precursor to the violence was the wedding of Mundra Devi, daughter of Chokhelal Jatav, a Scheduled Caste resident of Panwari village in Agra district. The wedding was scheduled for June 21, 1990, with the groom’s party arriving from Nagla Padma village. What would otherwise be a celebratory occasion became a flashpoint for caste tensions when members of the Jat community, who held dominant status in Panwari, objected to the Downtrodden (Dalit) wedding procession passing through what they considered “their” areas.

2.1 The Trigger Incident

Table: Key Facts About the Panwari Incident

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Date | June 21, 1990 |

| Location | Panwari Village, Sikandra Police Jurisdiction, Agra |

| Main Parties | Jatav (Downtrodden (Dalit)) Community vs. Jat Community |

| Trigger | Objection to Downtrodden (Dalit) wedding procession with groom on horseback |

| Initial FIR | Filed against 6,000 unidentified persons |

The Jat community’s opposition centered on the symbolic assertion of dignity by the Downtrodden (Dalit) community—specifically, the groom’s insistence on riding a horse during the procession, a practice traditionally reserved for Dominant castes. This objection was framed as a violation of caste norms that dictated strict social hierarchies. As one victim family member recounted: “The dominant ones announced that the groom would not be allowed to ride a horse”.

3 The Violence: Escalation and Aftermath

On June 21, 1990, when the wedding procession approached Panwari village, they were confronted by armed Jat men who had dug up roads, felled trees to block pathways, and gathered in large numbers to prevent the procession from entering. Despite the presence of local administrative officials and police personnel, the situation quickly escalated into a violent confrontation.

3.1 The Clash and Its Immediate Consequences

The confrontation turned violent when the hostile crowd—estimated between 5,000-6,000 people—attacked the wedding party. In the ensuing chaos, police opened fire, resulting in the death of Soni Ram Jat, a member of the Jat community. This death further inflamed tensions, leading to retaliatory attacks on Downtrodden (Dalit) homes and properties across Panwari and neighboring villages.

The violence quickly spread from Panwari to nearby areas, including Akola Udar village in the Fatehpur Sikri region, where Downtrodden (Dalit) localities were specifically targeted in organized attacks. The administration imposed a curfew across large parts of Agra district and deployed army troops alongside police and Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) to restore order.

3.2 The Extent of Violence

An eyewitness account from Bharat Singh Kardam, a victim whose family was permanently displaced by the violence, recalls: “We left the village in such a way that we could never return. We lost our home and land” . The violence resulted in:

- Large-scale arson: At least 15 Downtrodden (Dalit) homes were torched in Panwari alone

- Widespread injuries: Approximately 100 people were injured in the Akola Udar violence

- Forced displacement: Many Downtrodden (Dalit) families permanently left their villages

- Property destruction: Systematic damage to Downtrodden (Dalit) homes and possessions

4 The Legal Journey: Investigation, Delays, and Verdict

The legal process following the violence became a 34-year saga of investigative delays, witness intimidation, political interference, and judicial procedural hurdles that highlighted the challenges of delivering justice in caste-based violence cases in India.

4.1 Initial Investigation and Charges

The then Station House Officer (SHO) of Sikandra police station, Raman Lal, registered a case against 6,000 unknown persons on June 24, 1990, under various sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) including rioting, attempted murder, arson, obstruction of government work, along with violations under the SC/ST Act and the 7th Criminal Law Amendment Act.

After a prolonged investigation and recording of statements from 42 witnesses—including the then District Magistrate and Senior Superintendent of Police—police filed a chargesheet on January 29, 2000, against 18 accused . This 10-year gap between incident and chargesheet exemplified the initial investigative delays.

4.2 Judicial Proceedings and Delays

The trial faced multiple obstacles over the decades:

- Death of accused: 27 of the original accused died during the trial period

- Missing evidence: The original case diary went missing

- Hostile witnesses: Key witnesses turned hostile during trial

- Political protection: BJP MLA Chaudhary Babulal, a main accused, was acquitted in 2022

- Procedural delays: The case was transferred between courts and faced numerous adjournments

A particularly distressing aspect was that 188 individuals—many claiming innocence—were forced to attend court proceedings continuously for over 30 years, with many dying during this period. As one accused, now elderly, lamented: “We have been broken physically, mentally and financially by attending court” .

4.3 The Final Verdict and Sentencing

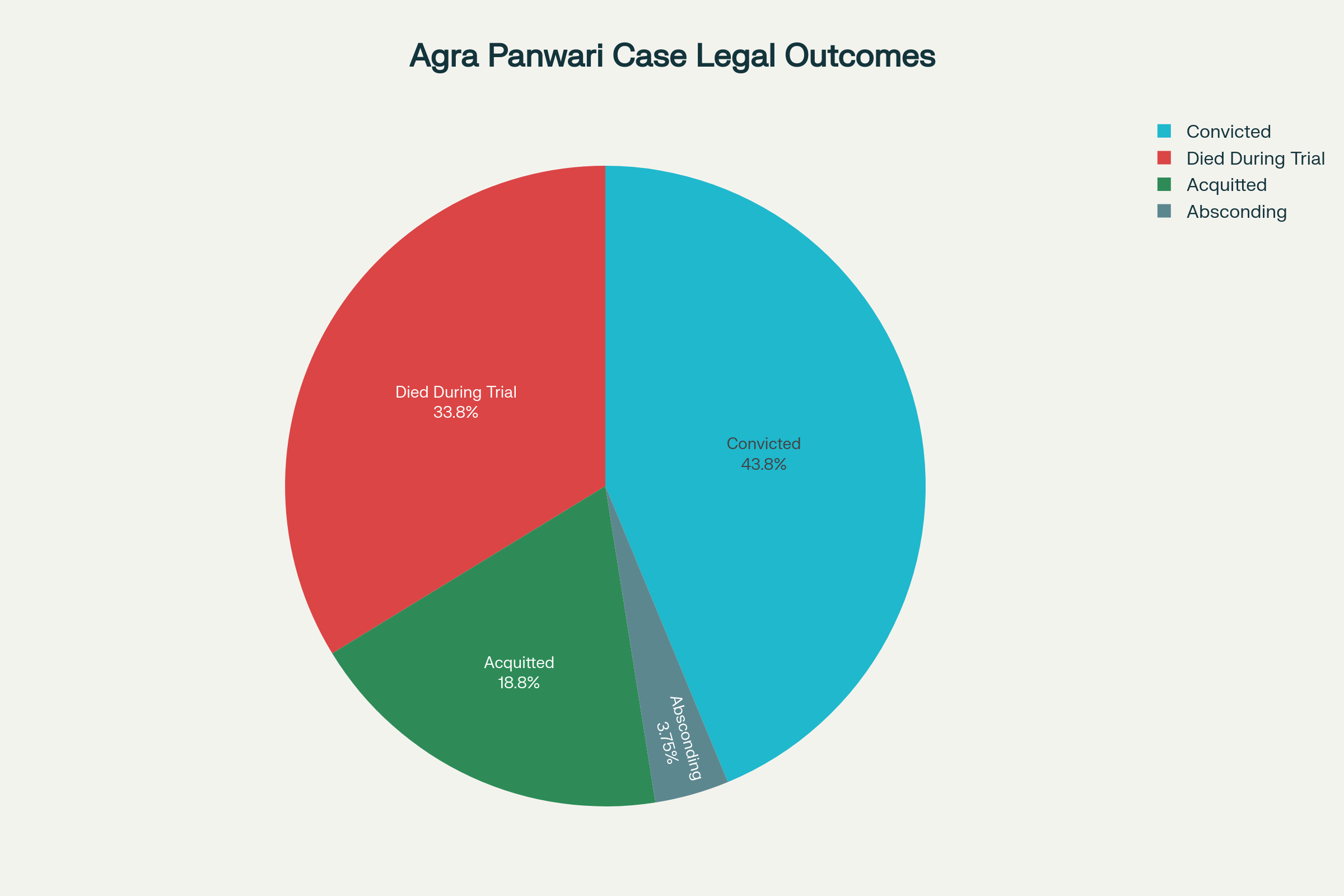

On May 28, 2025, Special SC/ST Court Judge Pushkar Upadhyay convicted 36 individuals while acquitting 15 others due to lack of evidence. The conviction was delivered under multiple IPC sections including 148 (rioting with deadly weapons), 149 (unlawful assembly), 323 (voluntarily causing hurt), 452 (house trespass), 436 (arson), and sections of the SC/ST Act.

On May 30, 2025, the court sentenced 33 convicts to five years of rigorous imprisonment and imposed a fine of ₹10,000 each . In a related case concerning the Akola Udar violence, 32 individuals were sentenced to five years’ rigorous imprisonment with a fine of ₹41,000 each, half of which was designated as compensation for affected Downtrodden (Dalit) families.

Table: Judicial Outcome of Panwari Case

| Judicial Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Total originally accused | 80 persons |

| Died during trial | 27 accused |

| Acquitted | 15 accused |

| Convicted | 36 persons |

| Key acquittals | BJP MLA Chaudhary Babulal (2022) |

| Trial duration | 34 years (1990-2025) |

| Sentencing | 5 years rigorous imprisonment + fines |

5 Socio-Political Impact and Reactions

The Panwari case transcended its legal dimensions to become a significant socio-political event that influenced Downtrodden (Dalit) politics in Uttar Pradesh and garnered national attention.

5.1 Political Reactions and Interventions

The incident sparked immediate political responses across party lines:

- Rajiv Gandhi, then Leader of Opposition, along with Sonia Gandhi, visited Agra and met with affected families

- Mayawati, then MP from Bijnor, raised the issue in Parliament

- The incident became a rallying point for Downtrodden (Dalit) political mobilization in Uttar Pradesh

- The ruling Mulayam Singh Yadav government faced criticism for its handling of the situation

The case also propelled the political career of BJP MLA Chaudhary Babulal, who despite being an accused, leveraged his role as a Jat leader to gain political prominence . His acquittal in 2022 drew criticism from victim families who alleged political influence .

5.2 Media Coverage and Public Discourse

The Panwari case received extensive media coverage that highlighted the persistent caste inequalities in rural India. The initial media narrative framed the violence as an attack on Downtrodden (Dalit) dignity and the constitutional right to equality. Over the years, the case became a reference point in discussions about judicial delays and accountability for caste-based violence.

5.3 Impact on Affected Communities

For the victim families, the aftermath was life-altering:

- Displacement: Many Downtrodden (Dalit) families never returned to their villages

- Economic hardship: Loss of homes, lands, and livelihoods

- Psychological trauma: Enduring fear and anxiety across generations

- Continued struggles: Even after rehabilitation, victims faced bureaucratic hurdles in regularizing government-allotted homes

Bharat Singh Kardam, whose sister’s wedding triggered the violence, encapsulated this suffering: “The violence did not just affect my sister’s marriage, it attacked the dignity of the Downtrodden (Dalit) community” .

The Broader Context of Caste Violence in India

Statistical Reality

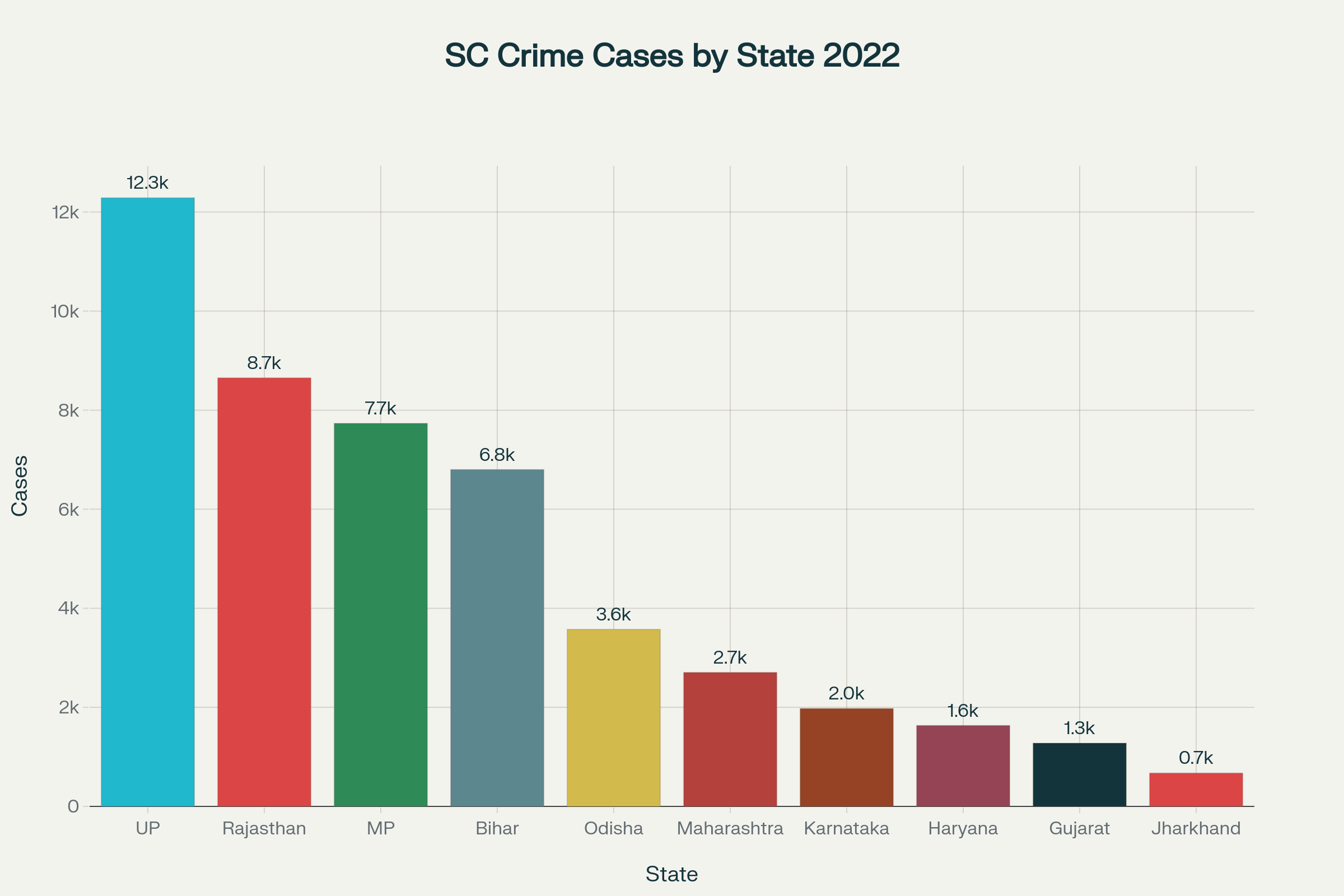

The Agra Panwari Case occurred within the broader context of systematic caste-based violence across India. According to recent government data, 51,656 cases of atrocities against Scheduled Castes were reported in 2022 alone, with the conviction rate declining from 39.2% in 2020 to 32.4% in 2022.

Uttar Pradesh, where the Panwari incident occurred, leads the country with 12,287 cases (23.78% of all cases) in 2022, followed by Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. This pattern demonstrates that caste violence is not an isolated phenomenon but a persistent social problem requiring sustained attention and intervention.

Wedding Procession Violence: A Recurring Pattern

The specific trigger of the Panwari incident—objections to a Downtrodden (Dalit) groom riding a horse—represents a common form of caste-based discrimination that continues to this day. Recent incidents across India demonstrate the persistence of this particular form of violence:

In Gujarat (February 2024), a Downtrodden (Dalit) groom was forcibly removed from his horse and subjected to casteist abuse with attackers claiming “only Thakors can ride horses”.

In Madhya Pradesh (December 2024), violence erupted when a Downtrodden (Dalit) family wanted to include a horse-drawn carriage in their wedding procession, leading to attacks on the wedding party and vandalization of the carriage.

In Uttar Pradesh (April 2025), a Downtrodden (Dalit) wedding procession was attacked over loud music, with the groom being pulled off his horse and assaulted.

These incidents highlight how traditional wedding customs become sites of caste assertion and resistance, turning moments of celebration into scenes of violence and humiliation.

Legal Framework and Implementation Gaps

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, which came into force on January 30, 1990—just months before the Panwari incident—was designed to address exactly these types of caste-based violence. The Act provides for:

- Specific punishment for caste-based offences with imprisonment ranging from six months to five years

- Special courts for expedited trials of atrocity cases

- Immediate arrest provisions without preliminary inquiry

- Relief and rehabilitation measures for victims

However, implementation challenges persist, as evidenced by the 35-year delay in the Panwari case resolution. The Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment has repeatedly highlighted that several states have failed to establish the necessary mechanisms to effectively implement the Act.

6 Conclusion: Reflections on Justice, Reconciliation, and the Road Ahead

The 34-year journey of the Agra Panwari case offers several critical insights into India’s continuing struggle against caste-based discrimination and the pursuit of justice for marginalized communities.

6.1 The Delayed Justice Paradigm

The Panwari verdict joins a growing list of cases where justice, while finally delivered, came after decades of waiting—raising questions about the effectiveness of legal protections for vulnerable communities. The fact that 27 accused died before verdict delivery underscores how judicial delays can effectively deny justice . The case highlights the urgent need for judicial reforms to expedite trials in caste-based violence cases.

6.2 The Political Economy of Caste Violence

The case revealed how caste hierarchies maintain themselves through violence and intimidation, and how political actors often instrumentalize these divisions for electoral gains . The acquittal of a politically connected accused while ordinary citizens faced conviction suggests the unequal application of justice .

6.3 Towards Reconciliation and Social Healing

Despite the protracted legal battle, there are glimpses of social transformation. Reports indicate that some villages now witness shared social practices between communities that were once in conflict. The verdict itself provides official recognition of the historical injustice suffered by Downtrodden (Dalit) communities, potentially enabling a more honest conversation about caste discrimination.

6.4 The Unfinished Agenda

While the judicial process has concluded its criminal aspect, the broader social justice agenda remains unfinished. Rehabilitation of victim families, compensation for historical wrongs, and ensuring non-repetition of such violence require sustained policy attention. The implementation of land reforms, economic empowerment programs for Downtrodden (Dalit), and educational initiatives promoting caste equality are essential to address the root causes of such violence.

The Agra Panwari case serves as a sobering reminder of the enduring power of caste in Indian society, but also of the resilience of those who struggle against it. As the convicted elderly men broke down in court upon hearing the verdict, and the victims expressed mixed feelings about justice delayed but not denied, the human cost of caste violence became palpable. The true measure of justice would be whether Panwari becomes a historical reference point rather than a contemporary reality in India’s ongoing journey toward caste equality.

6.5 Mayawati Tenure

Despite serving four terms as Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh (1995, 1997, 2002-2003, 2007-2012) and emerging as a monumental figure in Dalit politics, Mayawati’s tenures between 1990 and 2025 have been marked by unresolved justice for many marginalized communities. While her administrations were praised for improving law and order and empowering Dalits through symbolic gestures and affirmative action, this tented her legacy.